An email interview with Federico Casal in June 2017 for the online Uruguayan film magazine Revista Film. Casal has kindly provided me with this English version. — J.R.

EXCHANGE WITH JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

“I miss the experience of communal and theatrical filmgoing.”

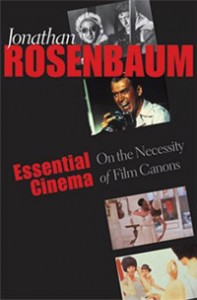

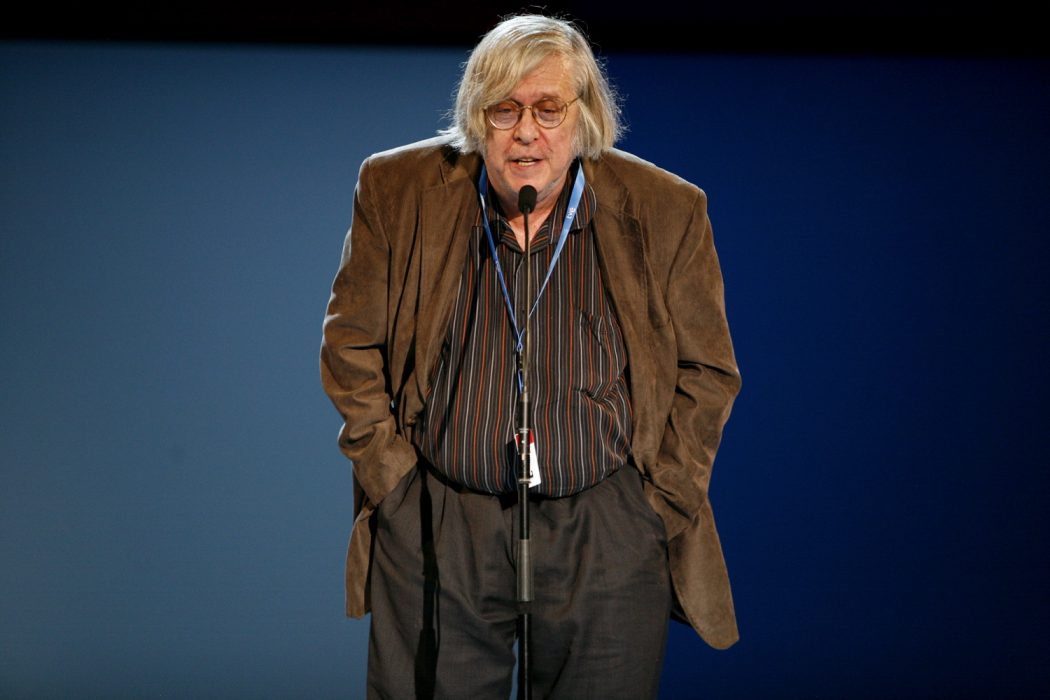

Jonathan Rosenbaum (born February 27, 1943 in Alabama, United States) is an American film critic with more than 50 years of experience. He has written thousands of articles and reviews, as the head critic of the Chicago Reader between 1987 and 2008, and collaborator in The Village Voice, Film Comment, Sight & Sound, Cahiers du Cinéma, Trafic, Film Quarterly, Criterion Collection, among others. He studied literature at Bard College in New York—there he met his most influential teacher, Heinrich Blücher, the German philosopher and second husband of Hanna Arendt. In 1969 he moved to Paris, shortly after which he became Jacques Tati’s assistant for a while and appeared as an extra in Robert Bresson’s Four nights of a dreamer (1971). From Paris he moved to London and then to California. Currently, he lives in Chicago. He has published numerous books on cinema, most recently Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia, Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Cannons and Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See, and others about Orson Wells, Jacques Rivette and Abbas Kiarostami. He also has a long international trajectory as participant in film festivals around the world, in some of which he was part of the jury (fun fact: he was a member of the jury at the BAFICI when the three main actors of 25 Watts (2001) were awarded, and at the UNAM International Film Festival when they gave a special mention to La vida útil (2010)). Praised by Godard, a continuer of Manny Farber and James Agee’s legacy, and a defender of multicultural cinema in a culturally isolationist country, Jonathan Rosenbaum is one of the indispensables of our time. A great part of his work can be found on his web site. He has also written about jazz and literature.

——————————————————————————————————————————-

In the last few years we have seen video essays proliferate, with varying degrees of scholarship and presentation, either on DVD/Blu ray extras or video sharing sites like YouTube and Vimeo. Moreover, anyone can have a space dedicated to sharing reviews or thoughts on films, such as on blogs or social media. With all of this in mind, what qualities should the present day professional film critic have to earn a position of authority?

Knowledge of film history, knowledge of history in general, some knowledge of the other arts, and a good grasp of spoken and written language. Also, taste—something harder to pinpoint but something that should be both defined and defended by the critic.

You have met Jacques Tati and Robert Bresson, among other directors. Do you perceive an essential difference in the way independent directors worked and thought about film back then and now?

I never had a proper conversation with Bresson, and I haven’t met enough studio directors to hazard any generalizations about either them or independent filmmakers, except to say that I believe that they all thought somewhat differently from each other. For example, I did know Sam Fuller pretty well, and I know that he had no trouble thinking of himself as an artist, which apparently wasn’t the case with Howard Hawks. Tati certainly thought of himself as an independent, but that doesn’t mean he ignored commercial considerations.

Pedro Almodóvar and Will Smith have recently incarnated the two sides of the Netflix debate, about whether or not films made for streaming services should participate in film festivals or be considered equal to theatrical releases. One could argue that some people fear that the increasingly personalized, consumer-oriented way of experiencing entertainment might make us less willing to take a chance with films outside of the familiar spectrum or go to the theater at all. On the other hand, streaming services offer audiences films from all over the world. Is there a real conflict here, or is the presentation secondary to the quality of a film?

I hate to make or even think about rules for everyone. I’ve never used Netflix or any streaming service, so I’m especially reluctant to think up rules for those who do. I don’t even know what positions Almodóvar and Smith hold on these matters. But I can at least say that the more venues that are open for people accessing films, the better. And my only thoughts about business rules is that they should be much less restrictive.

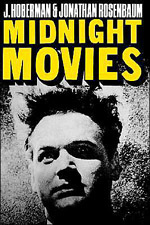

David Lynch has often said that the art-house is dead. One can assume he refers to the cultural environment in which Eraserhead premiered 40 years ago, as a midnight movie in a few independent cinemas, and the kind of public that came with that. Now, you’ve written a book with J. Hoberman on the subject. Do you share David Lynch’s sentiment or do you see that that world and spirit have taken another form?

The only commercial cinemas that I frequent in Chicago nowadays with any regularity are arthouses (the Landmark, the Music Box) or alternative venues such as the Gene Siskel Film Center. David Lynch seems to be speaking now as a businessman, not as an artist, and maybe he’s right from a business standpoint; I’m not at all qualified to comment on this subject. Jim Hoberman and I wrote Midnight Movies over 30 years ago, and the business has certainly changed a lot since then.

Would Erich von Stroheim be able to make Greed in 2017 as a 10 one-hour episode series for television?

What a provocative notion! I suppose that maybe he could have done that. Jacques Rivette did something roughly comparable in Out 1, but French TV refused it in the 1970s. Would they refuse it today? I have no way of knowing, and the same thing applies to Stroheim and Greed and North American cable TV.

You have been to countless film festivals over the years, and served as jury in many of them. What would your ideal film festival be like?

I guess it would be a cross between the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film (at least during 2001-2004, the only years that I’ve been able to attend it) and il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna (which I now attend every year). That is, a festival where a critical perspective and a sense of film history are both prominent, and where it’s easy to hang out with friends and talk about the films.

It is easier for an American film, whether big or low budget, to find global distribution deals. A Latin American film, on the other hand, might just have to conform with playing in its native country and in some film festivals. Do you see any of this changing?

I would like to see this changing, but until Donald Trump gets replaced by someone else, I wouldn’t expect this to change any time soon.

Your book Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons stresses the importance of maintaining certain masterworks, classical, international and contemporary, as quality standards and reference guides when thinking and writing about film. What are some of the characteristics shared by those films that make them “canonical”?

The only answer I can provide to this question is a personal response. For me, what makes them canonical is the number of times I can watch them without them ever seeming to lose their freshness. In other words, “canonical” equals “inexhaustible”.

In the Criterion essay about Playtime, you wrote: “The utopian vision of shared space that informs the latter scenes is made unthinkable by mobile phones, whose use can be said to constitute both a depletion and a form of denial of public space, especially because the people using them tend to ignore the other people in immediate physical proximity to them.” Have cell phones also been detrimental in some way to our appreciation of film?

Yes, and I’d go further and describe them as detrimental to all forms of concentrated attention. One thing that impressed me enormously about the Melbourne International Film Festival when I attended it last year was that I never saw another spectator checking her or his mobile once during any screening.

Do you miss anything in particular about the days when you started out?

I miss the experience of communal and theatrical filmgoing, mostly as a child in my family’s theaters in Alabama during the late 1940s and the 1950s. Part of that experience was quite clearly the experience of being part of a community, which is much harder to find and to feel these days in the United States—except, perhaps, on the Internet, where it’s a radically different notion of community, both physically and metaphysically.

If you had to move to a space station and could only take with you films from a single country, what country would that be and why?

It would probably be films from the U.S.—and not only because I’m an American myself, but also because I suspect that my country has produced the richest national cinema. On the other hand, if I was as fed up with American solipsism and arrogance and stupidity as I’m feeling at this moment, I might opt for French cinema instead, both in order to improve my limited language skills and as a better cultural reference point for what I believe culture and society might be—and also because France has a pretty rich national cinema of its own.

Your writing often analyzes a film’s politics even when the story is not directly making a social or political statement. Is a film’s political conscience an indicator of the filmmaker’s artistic maturity? Are there apolitical films? Should a filmmaker have a sense of social responsibility? Tarkovsky and Malick, for example, seem to be more concerned with atemporal, universal matters of the “soul,” than their characters’ relationship with society or the underlying economic tensions of their misfortunes.

Intentionality is often a hazardous and bogus criterion in film criticism. Regardless of their intentions, the films of Tarkovsky, which I admire enormously, are deeply misogynous, and the films of Malick, which I admire less, are the expressions of a football player. Both filmmakers are obviously talented as well as soulful individuals, but regardless of how apolitical they may be (or think they are) in terms of their artistic intentions, their films both reflect and have political and ideological aspects, some of which might be regarded as consequences.

Do you have any advice for the struggling young but hopeful filmmaker?

Don’t give up.

If you could live inside the world of a film, what film would that be and why?

Perhaps Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, because of the music and colors and people and feelings inside that film. I wouldn’t mind the food and the sex, either.

Do you have a personal top 10?

Theoretically, this list changes all the time, but for the moment, without thinking about it too much, my top ten are as follows (in no special order):

PlayTime (Jacques Tati, 1967)

Satantango (Béla Tarr, 1994)

Ordet (Carl-Theodor Dreyer, 1955)

Spione (Fritz Lang, 1928)

The World (Jia Zhangke, 2004)

City Lights (Charles Chaplin, 1931)

Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock, 1954)

The Wind Will Carry Us (Abbas Kiarostami, 1999)

Stars in My Crown (Jacques Tourneur, 1950)

The Magnificent Ambersons (Orson Welles, 1942)