From the Chicago Reader (September 2, 2005). — J.R.

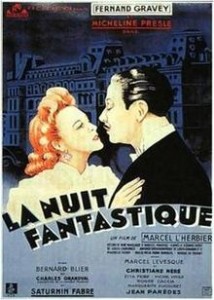

Made during the French Occupation, this 1942 feature by Marcel L’Herbier is a whimsical yet brittle nocturnal fantasy that consists mainly of a nerdy Parisian student’s expressionistic, romantic dream about pursuing an imaginary beauty. It’s the first film scripted by Louis Chavance, editor of L’Atalante and writer of the corrosive Le corbeau, and it oddly evokes both The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Eyes Wide Shut in its troubled moods and dreamlike studio settings (e.g., a formal ball at the Louvre, complete with magic show and trapdoors). Its illogical drift seems to convey the creepy collective unconscious of the occupation, so indelibly that even the happy ending turns out to be deeply disturbing. In French with subtitles. 100 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Part of a roundtable discussion with David Edelstein, Roger Ebert, Sarah Kerr, and A.O. Scott in Slate, December 26, 2001. Sorry that I can’t furnish the post from David that led to it. Note: let your cursor hit the first illustration below. — J. R.

Dear David (and Roger, Sarah, and Tony),

I appreciate your evocation of Sept. 11 at the start of your letter — a defining moment for us all — as well as your conflicted thoughts about vigilantism, and how these impact on your movie tastes. For me, there’s no conflict of this kind, because I’m afraid revenge strikes me as something less than an adult aspiration or concern — accounting both for why I think Mandela’s South Africa is far ahead of the United States in this respect and why In the Bedroom, a very well-made film, doesn’t interest me much. (The only moment I recall making my pulse race was when Spacek slapped Tomei.) As you’re the first to point out, Osama Bin Laden is also obsessed with vengeance — though surely not just for “slights against his brand of Islam.” Other beefs might include the deaths of about a million innocent Iraqis (the American Friends Service Committee’s estimate last spring) — collateral damage that Madeleine Albright told us she had no regrets about, despite the fact that it arguably only strengthened Saddam Hussein — as well as many other lethal forms of meddling in the Middle East, some of them slights against both humanity and common sense.

Read more

One of my “En movimiento”columns for Cahiers du Cinéma España, written specifically for their special Godard issue (December 2010). — J.R.

Writing recently here about the largely negative American reception of Film Socialisme at Cannes, I noted — in response to the implications of such critics as Todd McCarthy and Roger Ebert that the film’s difficulties could somehow be attributed to flaws in Godard’s character — that I was “impressed not only by the film’s singular, daring, and often beautiful employments of sound and image, but also by its tenderness towards virtually all the contemporary characters and figures in the film (including the animals) — a virtue I don’t find at all present in For Ever Mozart.”

One could, in fact, go through many portions of Godard’s filmography and cite works that are humanist (such as Bande à part, Masculin-Féminin, and France/tour/detour/deux enfants) and those that are relatively nonhumanist (such as Weekend, Vladimir et Rosa, and Passion). Even though one could argue that Godard’s self-imposed social isolation since his departure from Paris has had harmful effects on his art, it is too simplistic to assume that he’s always or invariably the simple grouch that many journalists have claimed him to be. Read more