From the Chicago Reader, June 18, 1993. (This is also reprinted in my 1997 collection Movies as Politics.) — J.R.

Who is correct? Are we becoming better off or worse off? Where are we heading? It depends on whom you mean by “we.” — Robert B. Reich, The Work of Nations

“Men never get this movie,” a woman says to her friend in Nora Ephron’s Sleepless in Seattle, referring to Leo McCarey’s 1957 An Affair to Remember, with Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr, which is showing on TV. In fact, we’re told this again and again. Another woman tearfully describes the last scene of An Affair to Remember to the hero, who remarks, “That’s a chick’s movie.” To clinch the point, female characters in this romantic comedy are repeatedly shown watching this movie and sobbing (as if the TV stations in Seattle and Baltimore, where most of the action takes place, showed little else), and men are never seen watching it at all. And just in case we’re left with any doubts about the matter, the review of Sleepless in Seattle in Variety assures us that An Affair to Remember‘s “squishy romantic elements appeal to women more than men.” Read more

This interview with Han Jian, reporter for the Bund Pictorial– a culture and lifestyle weekly based in Shanghai — was conducted for a cover story about American film critics planned for their February 17, 2015 issue. [Feb. 28: Now that I’ve been sent a link, it’s clear that the Chinese version of this piece is somewhat longer, because of an added introduction.]– J.R.

1. How did you become a film critic? Do you still remember your first film review?

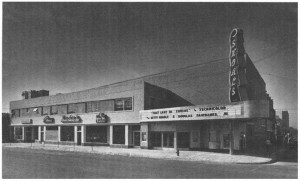

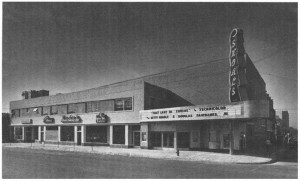

Much of this is described in my first book, an experimental memoir entitled Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980; second edition, 1995). I was the grandson and son of movie theater exhibitors in northwestern Alabama, which enabled me to grow up watching a great many movies for free. My father wrote a column for the local newspaper promoting the current releases, and shortly after my 14th birthday, I substituted for him one week, although this wasn’t actually a review. But the following year, I published my first actual film reviews — of The Astounding She-Monster, The Viking Women and the Sea Serpent, The Vikings, and a live TV drama called No Place to Run — in my high school newspaper. Read more

From the February 2014 Artforum; their title was “Beyond Good and Evil”. — J.R.

Claude Lanzmann, The Last of the Unjust, 2013, 16 mm and 35 mm, color and black-and-white, sound, 218 minutes. Claude Lanzmann and Benjamin Murmelstein.

THE LAST OF THE UNJUST, the latest of Claude Lanzmann’s footnotes and afterthoughts to his 1985 masterpiece, Shoah, functions even more than that earlier film as a dialectical palimpsest, so its successive layers — which remain in perpetual dialogue with one another — should be identified at the outset:

December 1944: Benjamin Murmelstein, a Vienna rabbi, is appointed by the Nazis as the third (and last) Jewish “elder” of Theresienstadt (Terezin, in Czech), a “model” or “showcase” ghetto set up in the former Czech Republic in 1941, his two predecessors having been executed the previous May and September. Murmelstein retains this position through the war’s end. Then, after spending eighteen months in prison for his collaboration with the Nazis, he is acquitted of all charges (although still widely despised as a traitor) and moves to Rome.

1961: Murmelstein publishes a book in Italian, Terezin: Il ghetto-modello di Eichmann, describing the suffering of the ghetto’s inhabitants.

1975: Lanzmann films an interview with Murmelstein over a week in Rome — the first interview that he films for Shoah, although he later decides to discard it, donating the unedited footage to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. Read more