From the Chicago Reader (September 26, 2003). — J.R.

Anything Else

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Woody Allen

With Jason Biggs, Christina Ricci, Allen, Stockard Channing, Danny DeVito, Jimmy Fallon, and Diana Krall.

The least valuable criticism we have of Charlie Chaplin maintains that he was a tremendously gifted comic until he started taking himself too seriously. My quarrel starts with the underlying assumption that the greatness of any comic artist can be measured with a laugh meter. I’ll readily grant that there’s more to laugh at in The Circus (1928) than in Monsieur Verdoux (1947), Limelight (1952), or A King in New York (1957), but that doesn’t make it a better movie. The other three offer some of the richest experiences in the history of cinema, and if quality of emotion counts for more than quantity, especially in comic works, they’re remarkable for their sharpness, depth, and complexity. They are all narcissistic reveries, yet none of them can be reduced to Chaplin assessing his own persona — though this is undoubtedly one reason they’re of interest.

I’d be prepared to make a similar case for the virtually impossible to find last feature of Preston Sturges, an independent effort known in French as Les carnets du Major Thompson and in English as The French They Are a Funny Race (1955). The critical consensus finds this work painfully unfunny, but that wasn’t my reaction when I managed to find a print in the early 80s. “Painfully unfunny” is the way I’d describe The Beautiful Blonde From Bashful Bend (1949), Sturges’s last Hollywood picture, but Les carnets was funny, albeit in an uncharacteristically quiet way — thoughtful and courtly rather than raucous and lunatic, as Sturges’s best pictures were. Viewers hoping for the old Sturges had their expectations dashed, and that apparently prevented them from seeing more fragile and less obvious traits — much as advocates of Chaplin’s tramp couldn’t get past his disappearance and appreciate the very different attributes of Verdoux, Calvero, and Shahdov.

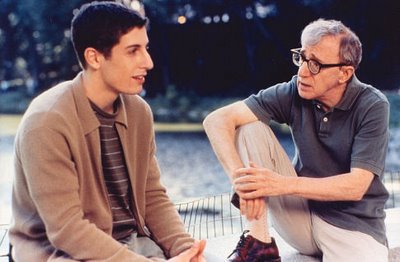

I didn’t laugh once during Woody Allen’s 33rd film as writer-director, Anything Else, and I can’t recall laughing much at his 32nd effort, Hollywood Ending, either, though at least I heard some laughter around me. It would have bothered me less this time if the emotions on view were more attractive. I was mostly curious to see Allen attempting to reinvent himself for the youth market — assigning many of his own familiar mannerisms to Jason Biggs (American Pie, American Wedding), a 25-year-old playing a 21-year-old aspiring New York writer, Jerry Falk, and assigning some of the same and a few other mannerisms to himself, a 67-year-old playing a 60-year-old grumpy writer and schoolteacher, David Dobel, Jerry’s mentor.

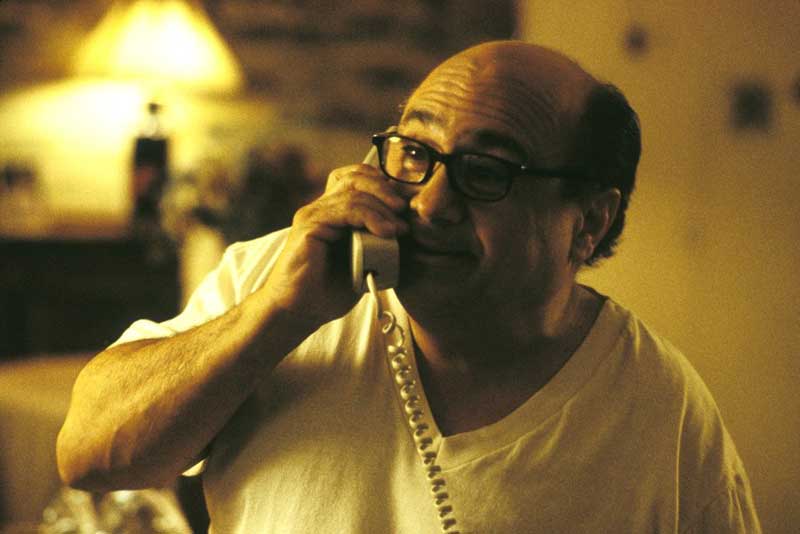

The film has periodic scenes with Jerry and Dobel walking through Central Park, each actor offering a slightly different version of Woody Allen shtick. But the heart of the film — if it can be said to have a heart — is in Jerry’s scenes with two other characters: the neurotic actress and aspiring singer he falls in love with, Amanda (Christina Ricci), and his dysfunctional and highly dependent agent, Harvey (Danny DeVito).

I don’t think it’s accidental that Amanda brought to mind Annie Hall (1977) or that Harvey conjured up Broadway Danny Rose (1984), my two favorite Woody Allen pictures. (I can’t count the 1966 What’s Up, Tiger Lily? as his funniest movie, because he didn’t direct it.) Amanda is introduced to us as a lovable shiksa goofball out of the Annie Hall/Diane Keaton mold; Harvey is presented as a lovable Jewish, or at least Jewish-style, loser out of the parade of showbiz might-have-beens who populate Broadway Danny Rose. The problem is, neither of them continues to be very lovable. Worse, we begin to realize early on that Allen hates both of them for giving Jerry such a difficult time, though they do so in almost antithetical ways — Amanda by rejecting and betraying him sexually, Harvey by clinging to him as if he were a life raft. These unpleasant traits quickly overwhelm whatever it is we’re supposed to love about these characters.

I don’t mean to imply that Allen isn’t being at all self-critical. Dobel isn’t just cranky — he’s paranoid and violent, nearly always seething with rage. Allen doesn’t present him as though he expects us to love him for these qualities. In fact, the self-hatred that’s Allen’s trademark is more obvious here than in any other character he’s played. If he expresses anything resembling sustained affection for anyone in this story, it’s for Jerry, who’s plainly intended to represent his younger and more hopeful self. I happen to find this affection almost as disagreeable as the hatred he expresses toward the three other leading characters, because it excuses too much. To all appearances, Jerry is just as big a hypocrite as Amanda. But he’s narrating the story, and it’s his view of himself that’s clearly meant to prevail.

This leaves us with only one other character who might be said to reflect the quality of this film’s emotions: Amanda’s mother, Paula, played by Stockard Channing, who also aspires to be a singer and moves into Jerry and Amanda’s apartment halfway through the picture. Paula is seen chiefly as an irritation and a threat to Jerry’s well-being, especially when she insists on renting a piano so she can accompany herself when she practices. But in one of her last appearances she interrupts his train of thought while he’s writing to sing him a song, and the film suddenly becomes intriguingly ambiguous. Is she supposed to be a good singer or a bad one?

For once, the film doesn’t tell us what to think, and we hang suspended. Paula/Channing isn’t a wonderful singer like Billie Holiday — a frequent reference point in the dialogue and on the sound track — or even like Diana Krall, whom we see as herself, singing and playing piano at the Village Vanguard, where Jerry and Amanda go to hear her. Furthermore, we wouldn’t think of Channing as a singer or a piano player in the first place, and she can’t be said to be singing precisely in tune. Yet the film clearly isn’t trying to say that she’s awful either. It’s something revolutionary in a Woody Allen movie: a moment when a character is neither wonderful nor awful. But then the plot returns to the usual bitterness.