From the May 1, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader. This marks the very beginning, the first baby steps, of my fascination with and research into the films of Yasuzo Masumura — an extended project that eventually culminated in a lengthy essay and a dialogue with Japanese critic Shigehiko Hasumi that’s included in a book called Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (2003) that I coedited with Adrian Martin. Although several Masumura films have subsequently become available on DVD in the U.S., the U.K., and France, including many of the films I discuss or mention here (e.g., Red Angel, Giants and Toys, and Manji in the U.S., Kisses in the U.K., and Tattoo in the France, the latter called Tatouage), I regret that several favorites — most notably A Wife Confesses and A False Student — continue to be unavailable outside of Japan (where Masumura has subsequently become a popular cult director). The first three illustrations and the very last one used here, incidentally, come from Tattoo [Irezumi] (1966) and A Wife Confesses (1961), respectively. –J.R.

To appropriate one of the categories of Andrew Sarris’s The American Cinema, Yasuzo Masumura (1924-1986) is a “subject for further research.” I’ve yet to come across a complete filmography of his work, but he’s said to have made 57 films, a dozen of which are showing at Facets Multimedia Center this week. I’ve seen six of his features, five of which are in the series, and no two are alike — though they do have traits in common. As I previewed these films I found that my professional duties and my predilections as a viewer pulled me in opposite directions. Over the next week I have at least half a dozen commercial releases to preview, but I’d much rather spend that time catching up with the seven Masumura features at Facets I haven’t seen — especially because I don’t expect to have many more chances to see them. (None of them is available on video.) This doesn’t mean I think all of these films would be equally good or interesting. But what I’ve seen of what Masumura brought to Japanese cinema over 20-odd years reminds me of many of the best things I’ve found in American commercial releases of the same era. In fact, recalling some of the things I discovered about Samuel Fuller, Nicholas Ray, Douglas Sirk, and Frank Tashlin when I read Sarris’s book back in the 60s, I realized that what I find most appealing in Masumura is something I find little of in current commercial fare — a sense of personal engagement with what’s happening in contemporary society. Mike Nichols, Steven Spielberg, and Quentin Tarantino could all take lessons from Masumura — as well as from Fuller, Ray, Sirk, and Tashlin — about how to speak personally about the 1990s.

The most significant facts I know about Masumura were gleaned mainly from a 12-page spread about him in the October 1970 issue of Cahiers du Cinéma. He was born August 24, 1924, in Kofu on the island Honshu and started going to movies at a very early age, having become friends in kindergarten with the son of a movie-theater owner. In high school he discovered Jean Renoir and Akira Kurosawa; he saw Kurosawa’s first feature (Sanshiro Sugata, 1943, recently released here on video) three times. After the end of World War II he entered the University of Tokyo as a law student but dropped out two years later and found a job working as an assistant director at the Daiei studio in Tokyo, where he earned enough money to return to college as a philosophy major and graduate in 1949. The following year he won a scholarship to study filmmaking at the Centro Sperimentale Cinematografico in Rome, where, according to some reports, Michelangelo Antonioni, Federico Fellini, and Luchino Visconti were among his teachers.

After graduating, Masumura assisted on an Italian-Japanese production of Madame Butterfly, then returned to Japan in 1954, where he worked at the Daiei studio in Kyoto as an assistant to Kenji Mizoguchi, perhaps the greatest of all Japanese directors, on three of his last features — Chikamatsu Monogatari (The Crucified Lovers) (1954), Princess Yang Kwei Fei (1955), and Street of Shame (1956). After Mizoguchi’s death, Masumura became an assistant to Kon Ichikawa, another major filmmaker, on three other films before shooting his own first feature, Kisses, in 1957. For much of the remainder of his career — my sense of his post-1970 work is cloudy — he remained at Daiei, making about three features a year, sometimes as many as four. In Japanese film history Masumura is a precursor of what’s generally known as the Japanese new wave, a movement that took root in the early 60s, around the same time as the French New Wave; it inherited its name from the French movement, though Nagisa Oshima, the figure most associated with the Japanese new wave, has said he always detested the label. Much as Jean Renoir, Robert Bresson, and Jacques Tati (as well as lesser-known figures like Roger Leenhardt and Alexandre Astruc, who functioned as critics as well as filmmakers) came to be seen as precursors of the French New Wave, Masumura was regarded as a major guru by Oshima before he embarked on his own career. Indeed, Masumura, director Nakahita Ko, and screenwriter Shirasaka Yoshio — who scripted at least ten of Masumura’s features, including Giants and Toys and A False Student — were all heralded by Oshima in a 1958 essay called “Is It a Breakthrough? (The Modernists of Japanese Film),” and Masumura was labeled the “possessor of the sharpest sociological perceptions of the three.” In lauding this trio Oshima, whose own first film was still about a year away, was celebrating their taste for youthful irreverence, their conscious methodology, and their call for freedom and innovation. Masumura, for instance, wasn’t applying the principles of Italian neorealism — what one might have expected given his formal training — but doing something closer to the reverse. As Masumura himself put it in a 1958 essay quoted by Oshima, the problem with social realism was that it gave too much emphasis to societal pressures, making the defeat of the individual all but inevitable and promoting an overall sense of resignation. “My goal,” Masumura wrote, “is to create an exaggerated depiction featuring only the ideas and passions of living human beings….In Japanese society, which is essentially regimented, freedom and the individual do not exist. The theme of the Japanese film is the emotions of the Japanese people, who have no choice but to live according to the norms of that society. The cinema has had no alternative but to continue to depict the attitudes and inner struggles of the people who are faced with and oppressed by complex social relationships and the defeat of human freedom….[But] after experiencing Europe for two years, I wanted to portray the type of beautifully vital, strong people I came to know there, even if, in Japan, this would be nothing more than an idea.” Masumura’s desire for an “exaggerated depiction” arguably stems from the same sort of impulse that led Oshima to systematically exclude the color green from Cruel Story of Youth (1960), his first color film and second feature. For Oshima, green signified the typical Japanese home, including its enclosed garden and tea cabinet, and “I firmly believed that unless the dark sensibility that those things engendered was completely destroyed, nothing new could come into being in Japan.” For Masumura, social realism, with its suggestion that change was impossible, was as deadly as the color green was for Oshima. In its place Masumura wanted to erect a fictional universe where freedom and individuality could take flight.

How does this translate into a cinematic practice? To oversimplify a little (and again, I’m judging from only six features), it means creating a cinema of crazy people — films about fanatics — and never displaying a trace of sentimentality about them or anyone else. As Canadian critic Mark Peranson puts it, “[Masumura’s] movies are about the freedom to do whatever the fuck you want, and the ramifications of taking this attitude when society won’t accept it.” The same could be said of some of the best films of Fuller, Ray, Sirk, and Tashlin, many of which flirt with madness — individual as well as collective — and chart the ensuing social consequences.

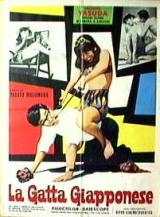

In Masumura’s work this craziness ranges from the hysterical, as three competing candy companies run promotional campaigns in the Tashlin-esque Giants and Toys (also known as The Build-up, 1958), to the calmly reasoned, as an army nurse during the Sino-Japanese war dispenses sexual favors to an amputee in Red Angel (1966). There is also the slow-witted young man in A False Student who poses as a college student, joins a Maoist study group, and eventually goes nuts after being mistaken for a police informer. And the tea master in the relatively lackluster Thousand Cranes (1969) who methodically sets about sleeping with his late father’s girlfriends. In the first Masumura film I ever saw — a 1967 feature known in France as La chatte japonaise (“The Japanese Cat”) and elsewhere as Love for an Idiot — there’s the madness of a middle-aged businessman who trains, marries, and then loses a much younger wife; crazed by his fond memories of crawling around on all fours while she rode him piggyback, he tries to simulate the same activity alone in his apartment.

In some of these films — Giants and Toys, A False Student, Red Angel — madness, or the “madness” that seems sane in an insane climate, is a consequence of a monstrous conformity found respectively in the worlds of advertising, politics, and war; in others — Love for an Idiot and Thousand Cranes — it points to private demons that other things in society have unleashed. Either way, Masumura tends to be lucid about what this madness consists of and what it has to contend with: the outcome of the struggle of various characters with their own manias or with the manias that surround them is invariably determined by their ability to sustain their integrity as individuals.

Oddly enough, this craziness seems least apparent in Masumura’s first feature — known as Kisses, The Kiss, and A Kiss — an excitingly photographed teenage love story that recalls Nicholas Ray and is well worth seeing. There’s a big difference between what constituted provocation in 1957 Japan and what might seem daring elsewhere; it’s worth noting, for instance, that on-screen kissing wasn’t permitted in Japanese cinema until after World War II, so even the title is likely to carry a slightly different charge on its home turf. (Similarly, the Maoist demonstrations at the university in the 1960 A False Student are intriguingly out of sync with the comparable demonstrations in the West that would erupt several years later.) The hero and heroine of Kisses — a bakery delivery boy and an artist’s model — meet while visiting their respective fathers in prison; his father is serving a term for an “election day violation,” hers for stealing money to pay her mother’s hospital bills. Not wanting her mother to know that her husband’s in jail, the model is seriously considering prostitution to raise the money for her father’s bail so he can go visit his wife in the hospital. (Twisted yet subtle moral decisions of this kind are characteristic of the dilemmas faced by Masumura’s heroines. Generally identified as a “woman’s” director, much as his mentor Mizoguchi was, he tends to accord more moral consciousness to his female characters. In the extraordinary Red Angel a war nurse who’s raped subsequently exchanges her sexual services for a pint of blood that might save the life of her rapist; ostensibly she doesn’t want him to die because he might think she’s taking revenge. The heroine in A False Student has comparable scruples when it comes to dealing with the sanity then madness of the title imposter.) After a few false starts the relationship between the delivery boy and the model blossoms when he takes her to the beach, then to dinner at a dance hall; he even accompanies her on the piano while she sings what appears to be the title song, but winds up deserting her at the end of the evening when she asks him to declare his love. According to Japanese critic Tadao Sato, the film was ignored by critics when it came out because of its presumed similarity to other youth films of the period: only later did it become apparent that Masumura was rejecting many of the trappings of the genre. “His hero was neither mild-mannered, romantic, nor especially good-looking, but rather audacious and perpetually angry,” Sato writes. “He was not the first Japanese version of the angry young man — rich, profligate youths had to some extent raised hell before him — but he was the most significant because he was a poor boy from the masses. In contrast to previous youthful heroes, he gives vent to his frustrations through exaggerated actions rather than through languishing melancholically, for sympathy is the last thing he wants. Thus, there are no atmospheric props or sentimental effects in Kisses, and the young hero is going to fulfill his thwarted needs through action alone.”

Thanks to its fluid, airy black-and-white cinematography, Kisses is beautiful to look at — as are the less fluid but very artfully composed A False Student, and the more expressionistic Red Angel, both of which are also in black and white. By contrast, the color cinematography in Giants and Toys is uniformly garish and ugly — I’m sure deliberately, as all the film’s characters are uniformly unpleasant — whereas the color in Thousand Cranes and Love for an Idiot is functionally attractive, though not necessarily in the same ways. All of which is to say that a persistent, recognizable visual style is not part of Masumura’s ongoing strategy as a filmmaker. “I don’t subscribe to the cult of the image,” he declared in 1969. “I think that a film should have a construction, a plot, an evolution — in short, its own structure.” But in the same interview he maintained, “I never use close-ups. I detest them. Why do a close-up of an actor or actress’s face? I’ll agree to do a close-up if it’s the real face of a peasant, for example…[but] the performance of actors has no interest because it’s finally a lie and doesn’t wind up with anything beyond a certain ‘resemblance.'” Lest this sound like an overall denigration of actors, it’s worth noting that Masumura developed what amounted to a repertory company of favorite actors, including Hiroshi Kawaguchi (the male lead in both Kisses and Giants and Toys) and Ayako Wakao (the female lead in A False Student, Manji, Seisaku’s Wife, Red Angel, and The Wife of Seishu Hanaoka; she also played in Mizoguchi’s Street of Shame). He also directed one of Mizoguchi’s main actresses, Machiko Kyo, in what might have been her last performance, in Thousand Cranes; and director Juzo Itami plays a featured role in A False Student.

What is persistent in Masumura’s work, apart from a few actors, is a certain ethical engagement with the world — and a set of strategies for pursuing and sustaining that engagement, such as the privileging and exaggeration of obsessive forms of behavior. Partly for this reason, judging from what I’ve seen, nearly all his films are deeply erotic on some level. Because women’s sexuality often serves as coin of the realm in Japanese society — at least as Masumura and many of his compatriots view that society — the way that these women’s “fortunes” get saved, spent, or squandered within that economy remains a profound ethical issue, and I can think of few directors apart from Masumura and Oshima who’ve made sexier movies that are also frank about their political concerns. In a society where individuality can often be expressed only in a sexual realm, eroticism becomes an exploration of political freedom. If one wants to understand why Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses is a profoundly political (and antiwar) film, Masumura’s oeuvre and all it implies points one in the proper direction.