Written for Sight and Sound.

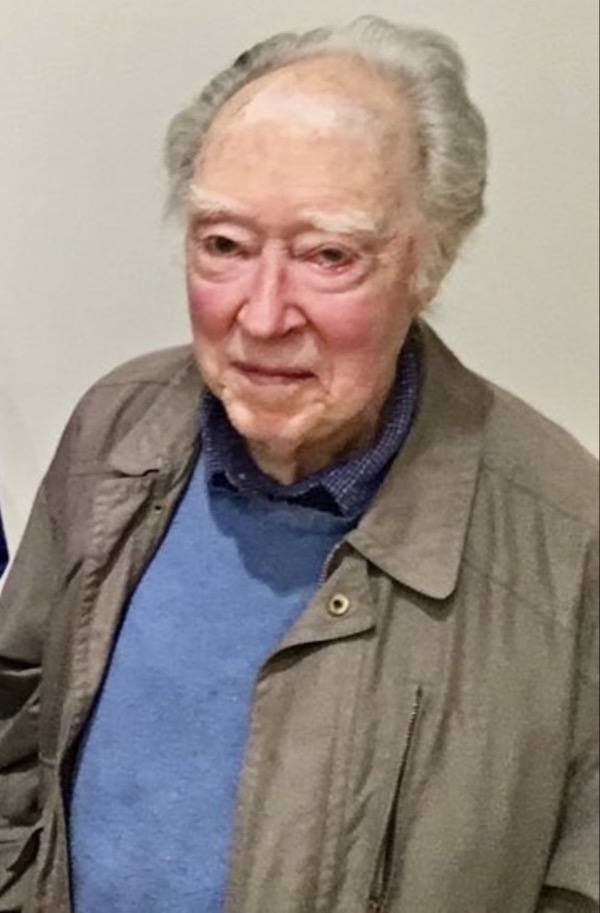

Manny Farber, one of his earliest critical defenders, once described Michael Snow to me as “a prince”, and there’s no question that he was a proud bohemian who carried his own sense of royalty within the art world with grace and style. European fans such as Jacques Rivette who mistook him for an “American” (he was born and died in Toronto) may not have understood that the state funding that allowed Snow to flourish in Canada wouldn’t have been as feasible in the U.S. It’s even been speculated that if Snow hadn’t filmed his 1967 Wavelength in a Manhattan loft during his extended New York sojourn, many of us might never have heard of him. It was basically the enthusiasm of New York critics—Farber, Jonas Mekas, Annette Michelson, and, perhaps most of all, P. Adams Sitney and his term “structural film”—that placed Snow on the map, even while such reference sources as Ephraim Katz’s A Film Encyclopedia and David Thomson’s A Biographical Dictionary of the Cinema failed to acknowledge his existence.

Starting out as a self-taught jazz pianist who evolved from Dixieland to bebop (and later, to free jazz), Snow turned next to painting, sculpture, instillations, photography, film (starting in animation), video, holography, audio, and conceptually shaped books such as Cover to Cover (1975) and High School (1979). As J. Hoberman recalled in his thoughtful New York Times obituary, Snow announced in 1967, ‘I am not a professional. My paintings are done by a filmmaker, sculpture by a musician, films by a painter, music by a filmmaker, paintings by a sculptor, sculpture by a filmmaker, films by a musician, music by a sculptor… sometimes they all work together […]’

Like Godard, he produced a veritable avalanche of works, robust, playful, loaded with puns and measured afterthoughts, and often self-referential or cross-referential. (The “walking woman” in many of his early paintings, for instance, reappears either figuratively or literally in some of the films. And his magisterial 1979 Flight Stop, a photographic sculpture of sixty fiberglass landing geese in a huge Toronto mall, is quintessentially cinematic, or at least precinematic.)

And when he took up film, he characteristically wound up reinventing the medium on his own terms—exploring camera movement in his famous trilogy of Wavelength, — (Back and Forth, 1969), and La région centrale (1971), sound and image juxtapositions in ‘Rameau’s Nephew’ by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen (1974), and digital shape-shifting in *Corpus Callosum (2002), to cite only five of his major works.

It’s remarkable that Snow should die at age 94 only a few weeks after the deaths of Godard and Straub—not because these innovative giants all inhabited the same universe but because they were all frequently greeted, rejected, or ignored with a great deal of confusion. (I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that most people reading this obituary “know” Wavelength, if at all, only through Martin Scorsese’s brief homage to it in Taxi Driver, or at least Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson’s allusion to it in “The Power and the Gory”.) Considering Godard French rather than Swiss and not knowing that Straub came from a city that was alternately French and German suggests an easy parallel with Rivette’s confusion about Snow.

Independent American filmmaker Jon Jost has praised the concepts behind Wavelength and La région centrale but faulted the executions of those films as lazy and slipshod (while adding that hallucinogenic drugs helped to make their alleged failings more tolerable), while the late Argentinian writer-director Eduardo de Gregorio told me that what impressed him the most about Snow’s work was its technical precision. One reason why it’s impossible to reconcile these seemingly antithetical responses is that Snow’s experimental cinema, unlike the radical art cinemas of Godard and Straub, refuses any relationship to mainstream cinema, either positive or negative. Whereas Godard and Straub situated themselves in relation to film history, Snow, whose interest in film history was minimal, placed himself in the history of art. Consequently, the received ideas we have about mainstream cinema, derived from such sources as Oscars and other forms of industry propaganda (including the assumption that the only films worth mentioning are industrial products) can’t be applied in any meaningful way to Snow’s work, which has scant interest in either storytelling or narrative verisimilitude. The closest it gets to mainstream cinema are occasional forms of mockery or defiance, such as placing the credits in the middle of a film.

Another thing that clearly distinguished Snow from Godard and Straub, at least in my encounters with them, was his relative serenity. After I was commissioned to interview him in Toronto about his Presents in 1981, we became friends, so that I spent enjoyable evenings smoking grass with him at his Toronto home and then going to Chinatown for dinner (and once attending one of his weekly free-jazz jam sessions). Our friendship led to a second interview about his minimalist film So is This (1982), and it ended only after I published a book in 1983 that criticized two of his New York champions. But even when he expressed his disapproval–which might have been exacerbated by my probing of his political incorrectness involving women in Presents (as with Kubrick, his sense of humour sometimes resembled that of a teenage boy)–he remained a gentleman about it.

In Wavelength, we lurch across a room in a series of zooms overlaid by numerous shifts in colour and texture: in Back and Forth, we’re shuttled back and forth in a series of horizontal and vertical pans in a classroom; in the three-hour La région centrale, set in a mountain wilderness, we rotate in 360-degree loops every which way. Like Godard and Kubrick (filmmakers for whom he showed some interest), Snow regarded film as a vehicle for thought and exploration, which should situate him within our grasp of film history, if not necessarily within his. The sensuality of thought was part of what intrigued him, making the camera movements of his trilogy both challenging and rewarding, like demonic fairground rides that constantly oblige us to readjust. Associating a flow of ideas (mainly philosophical) with a sensorial experience refutes the very notion of intellectual activity as an alternative to “life”, as a Puritan mindset might have it, and Snow’s almost carnal form of engagement actually gives us plenty to think about.

His notion of camera movement as aggression receives two comic postscripts that could serve in a way as alternate versions of Wavelength and Back and Forth, respectively: Breakfast AKA Table-Top Dolly (1976), a short in which a transparent sheet in front of a camera lens crushes a lot of groceries, comically equating camera movement with mastication and/or digestion, and the opening sequence of Presents, in which a stage set with actors is no less messily demolished by forklifts shaking it, with the forklifts becoming a surrogate for the camera as it wreaks its destruction.

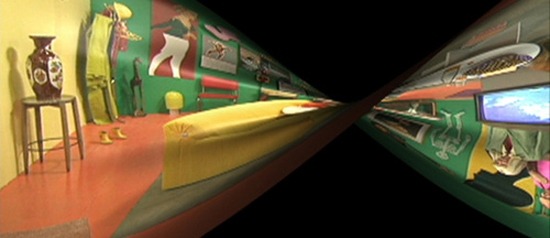

For me, *Corpus Callosum remains Snow’s greatest film, not only because it manages to encapsulate so much of his previous oeuvre (even concluding with a bit of animation from his earliest film work), but also because it manages to combine, seemingly for the first time in his career, an acute sense of social history with its formal, technical, and comic hijinks. Exploring the progression (and/or regression) from analog to digital, the film oscillates between (a) a workstation in a skyscraper with wall-sized windows and employees seated in front of computers and (b) a windowless bunker with a family seated on a sofa in front of a TV, emblematic of half a century earlier. The various rhymes and clashes between these sites, as well as the digitally generated distortions of bodies and spaces within both, are endlessly suggestive.