From the Chicago Reader (April 24, 1992). — J.R.

MY COUSIN VINNY

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Jonathan Lynn

Written by Dale Launer

With Joe Pesci, Marisa Tomei, Ralph Macchio, Mitchell Whitfield, Fred Gwynne, Lane Smith, and Austin Pendleton.

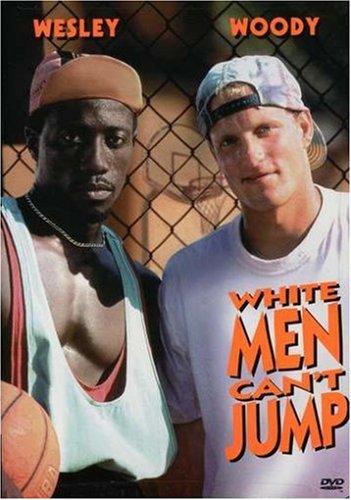

WHITE MEN CAN’T JUMP

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Ron Shelton

With Wesley Snipes, Woody Harrelson, Rosie Perez, Tyra Ferrell, Cylk Cozart, and Kadeem Hardison.

“Why is this film so popular?” Michael Sragow asked a little plaintively about My Cousin Vinny in the New Yorker last week. Then he suggested an answer: “Perhaps because it gives Pesci a chance to combine his commercial signature, pop scabrousness, with old-fashioned virtues like ‘heart.'” This hypothesis implies that audiences go to comedies for highly esoteric reasons — just like some film critics.

Personally, I’d rather believe that My Cousin Vinny is popular for reasons that have more to do with reality and recognition — specifically, with an appreciation of American regionalism that most contemporary American movies never even attempt, much less convey. At least that’s what I like about the movie, and it’s also what I like about White Men Can’t Jump, the other most popular American comedy around at the moment. These movies, both produced at Twentieth Century Fox, have lots of other things in common as well. Both kick off and end with buoyant, percussive, down-homey music. Both have somewhat boyish heroes, immature and unsettled, and sexy, practical-minded ethnic heroines who wind up saving their boyfriends from doom with their unlikely funds of encyclopedic knowledge. But most important, both movies show worlds striking for their remoteness from shopping malls.

Ever since malls and mall culture started to take over and define mainstream American consciousness, regionalism has become an increasingly scarce commodity — so much so that whenever it does turn up in movies it’s tinged with a certain nostalgia. I would wager that part of what’s appealing to many people about both these new comedies is that they’re steeped in the idiosyncrasies of specific locales, languages, and life-styles, all of which predate malls’ homogenized cultural anonymity. Moreover, both these comedies are structured around the juxtaposition and interaction of two distinct cultures within a single fixed, formal arena — a courtroom in My Cousin Vinny and various basketball courts in White Men Can’t Jump. Spiking the competition between cultures is the fact that the filmmakers refuse to declare one side good and the other evil. (Each movie has a specific moral scheme but doesn’t require any serious villains to illustrate its sense of wrong.) Though the story lines of both movies may be ragged, improbable, and unevenly motivated in spots — Vinny slips a meaningful note to the sheriff at the eleventh hour of My Cousin Vinny, and the hero’s girlfriend in White Men Can’t Jump gets on Jeopardy — they still seem to be unfolding within a reasonable facsimile of the real world.

There’s no ambiguity about the two competing cultures in My Cousin Vinny. They’re the rural south, where the movie is set, and Brooklyn, which is embodied in the movie’s hero and heroine, Vinny Gambini (Joe Pesci) and his fiancee Mona Lisa Vito (Marisa Tomei). Vinny and Lisa go to Wahzoo City, Alabama, so that Vinny can defend his teenage cousin Bill (Ralph Macchio) and Bill’s friend Stan (Mitchell Whitfield), both of whom are from New York. While driving through the south on a holiday they’ve been wrongly accused of murdering a convenience-store clerk. The circumstantial evidence against Bill and Stan is massive, and to make matters worse, Vinny just passed his bar exam, on the sixth try, a few weeks before and has never been in a courtroom. Most of the movie is a variety of Capracorn in which the totally ineffectual little guy triumphs over outsize odds — among them an inflexible southern judge (Fred Gwynne) who questions Vinny’s credentials from the outset. But what’s really at stake is the pride of two battered underdog cultures, both of them hidebound, provincial, and sluggish — highly resistant to any form of change, including growth or compromise.

Neither the screenwriter nor the director of My Cousin Vinny is an insider of either culture — although unlike the touristic observers characteristic of most Hollywood junk they’re far from disrespectful or inattentive. Writer Dale Launer, who also wrote the comedies Blind Date, Ruthless People, and Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, was born in Cleveland and raised in southern California; director Jonathan Lynn, who also directed Clue and Nuns on the Run, is an Englishman known for his work in TV comedy as a writer, actor, and director.

While they’re clearly amused by the provincialism of both the south and Brooklyn, Launer and Lynn are charmed by these cultures’ old-fashioned virtues. But fortunately they aren’t so charmed that they idolize or patronize any of their characters: they’re equally deft on the bickering mating rituals of Vinny and Lisa and the blinkered self-congratulation of the white southern gentry. (When Lane Smith’s district attorney glibly explains in court how a legal term “comes down from England and all our . . . ancestors there,” there’s a brief cut to attentive jurors, two of whom are black.) Brooklyn and Alabama glitz and sleaze are made to seem a little quaint and silly at times, especially when the cultures collide headlong, but they’re never treated with a snobbish sense of superiority. It’s a good sign that the actors show some real appreciation of regional slang and accents; part of what makes both newcomer Tomei and old-timer Gwynne — as well as Pesci and Smith — so enjoyable here is what they casually manage to do with Brooklyn and southern speech.

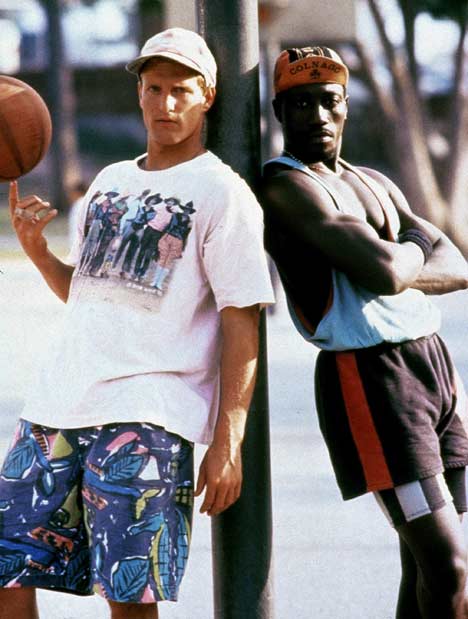

Though the two cultures and lingos highlighted in White Men Can’t Jump are somewhat less clearly defined, they’re still at the center of the movie. The black working-class neighborhoods of Venice, California, where the movie is set, collide with white southern culture, embodied in the film’s hero, Billy Hoyle (Woody Harrelson), a basketball hustler who once played college ball in Louisiana, now in flight from racketeers. The movie is at its best when contrasting Venice’s grimy everyday textures at their least glamorous with the extravagant language employed by Billy, the black hero Sidney Deane (Wesley Snipes), and the other black basketball players they rub elbows with. Once again the competition is between two underdog cultures, in this case the white south (restricted to the character of Billy) and the black working class.

The meeting point between these cultures is precisely articulated in the film’s opening sequence, behind the credits, which summons up at least as much nostalgia as the vistas of the deep rural south that open My Cousin Vinny: Billy pauses to listen appreciatively to a trio of black men (Bill Henderson, Sonny Craver, and Jon Hendricks) singing a jazzy rendition of “A Closer Walk With Thee” on the Venice beachfront, to the sprightly accompaniment of a guitar and brushes on a snare drum. After the musicians get him to drop some money in their hat, Billy says, “Sing some more. My old man was a preacher — I love this shit.” It’s the only thing we ever learn about Billy’s family, but it does establish a crucial link between these two oral cultures.

Billy meets Sidney shortly afterward and teams up with him for some basketball hustles. Sidney subsists mainly on his part-time jobs and hustling, though he’s married and has a little boy, and his wife Rhonda (Tyra Ferrell) pressures him to let her work and to move from their apartment to a house in a safer neighborhood. Sidney is a less clearly imagined character than Billy, and director-writer Ron Shelton’s relative distance from him is signaled in a number of ways, but Snipes does such a remarkable job of playing him — this is the most fully rounded and energetic performance I’ve seen from him — that you’re inclined to overlook the fuzziness. (This is somewhat harder to do when it comes to the insubstantial Rhonda, who’s barely imagined at all.) Serving as something of a mentor to Billy, Sidney effectively critiques and explains the white hero to us, but he’s less of a full-blown character in his own right than one might wish. In a lot of ways this movie is as much a hustle as one of the scams it depicts, but it’s so good-natured and up-front about it that one easily forgives the script’s evasions for the sake of the surface glitter. (The basketball playing is pretty lively, too, even for someone like me who’s allergic to sports.)

With his third feature, Shelton fully and finally establishes what might be called his auteurist credentials. These include a special feeling for sports and southern jive — though oddly enough, while he has a substantial background in baseball and basketball, his skeletal biography in the press kit makes his tenure in the south seem rather limited. (He was born and raised in southern California, where he also attended college on a sports scholarship, though he was signed by the Baltimore Orioles after graduation and played on minor-league teams in Florida and Texas.) Still, the southern elements in Bull Durham, Blaze, and White Men Can’t Jump are unmistakable, and extend to more than just the settings and a flowery and overripe sense of speech. (Blaze isn’t concerned with sports — unless one places southern politics and/or burlesque shows in that category — but then again, because it stars Paul Newman, it’s more a Newman movie than a Shelton movie, much as The Color of Money is more Newman than Scorsese.) If it’s possible to hypothesize a southern filmmaker’s worldview, distinct from dialects and settings — a particular blend of communal interaction, oral culture, sweaty sex, macho peevishness, and romantic hyperbole — Shelton clearly has at least as much of it as King Vidor, a certifiable born Texan.

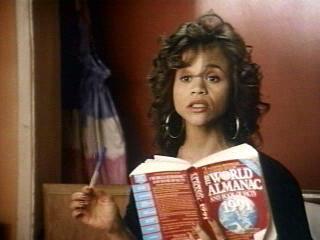

Both Bull Durham and White Men Can’t Jump feature a similarly gifted and emotionally stunted athlete — Tim Robbins in the first, Woody Harrelson here — and a similarly wise, wordy, and philosophical heroine. (In Shelton’s original script, the white hero’s girlfriend more closely resembled Susan Sarandon in Bull Durham — an upper-class white college type from Smith or Barnard. But when Do the Right Thing‘s volatile Rosie Perez tested for the part, she did so well that Shelton altered his conception accordingly.)

Four years ago in the Reader I questioned whether Shelton’s comic talents had anything to do with those of Preston Sturges. But considering the rags-to-riches pendulum swings of the new movie, including the heroine’s appearance on Jeopardy, I’m not so sure they don’t. Still, one difference between Sturges and Shelton as writers of dialogue is that Shelton’s jazzy riffs usually don’t survive as well on the page. A great deal of what enlivens White Men Can’t Jump — even more than the basketball playing — are the insults and other verbal inventions traded among the black players, but what’s funny and wonderful about them can’t really be transcribed the way that most of Sturges’s best talkfests can be. They’re really triumphs of performance as much as writing, and like the basketball playing they probably seem improvised and effortless only because they were rehearsed carefully and repeatedly.