From The Village Voice (May 13, 2008). — J.R.

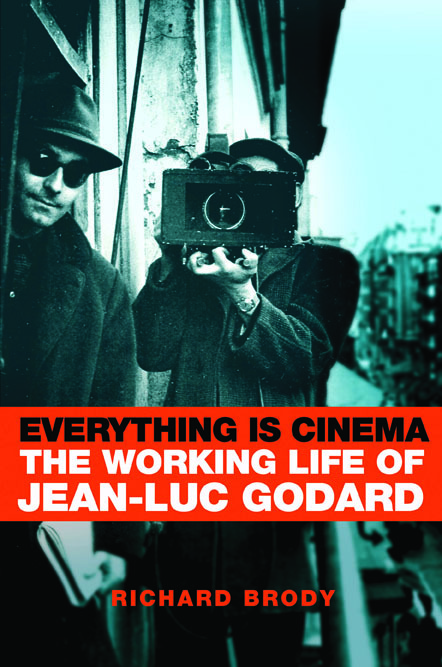

Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard

By Richard Brody

Metropolitan Books, 701 pp., $40

Will we ever get a critical biography of Welles, Kubrick, or Eastwood as good as Brian Boyd’s two volumes on Vladimir Nabokov? Probably not. Novelists basically have friends, relatives, and editors to be interviewed, but with high-profile movie directors, one also has to contend with countless employees, potential as well as actual. And the complications introduced by showbiz gossip about mythical and controversial figures are endless: While these stories make for compulsive reading, they interfere with criticism and scholarship.

With all that extra and unwieldy baggage in tow, a biographer may find it impossible to create a critical through-line that’s both persuasive and comprehensive. Even in the best books of this kind, either the life overrides the films (as in Joseph McBride’s Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success) or the criticism trumps the biography (as in Chris Fujiwara’s Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall). And taking on a maven as prolific, innovative, and constantly changing as Jean-Luc Godard, biographer Richard Brody is clearly asking for trouble.

Perhaps the most impressive thing about Brody’s Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard is that it’s 700 large-format pages long, yet winds up seeming too short — a tribute to both the author and his 77-year-old subject. It’s roughly twice the size of its only predecessor, Colin MacCabe’s Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy (2003), yet Brody wastes little time retracing the steps of MacCabe’s most valuable research, which concentrated on Godard’s first 25 years. But Brody does draw attention to the anti-Semitism and Vichy-friendly background of Julien Monod — Godard’s maternal grandfather, who was also Paul Valéry’s literary executor — and this has increasing importance as the book develops.

Brody’s main strength, apart from the fact that he’s never boring, is his ease in clarifying the intricacies of French politics and philosophy as they interact with Godard’s evolution. Sometimes these two specialties even come together, bristling with Godardian paradox: “Breathless was both a work of existential engagement with the world — an engagement that was constant, essential, and involuntary, inasmuch as it was a collage of preexisting material — and therefore also a work of Sartrean bad faith, made by a thinker who did not think but was thought.”

But insofar as Godard’s life and work have often been impossible to differentiate, distinguishing between the pertinent and the peripheral is no easy matter. Anne-Marie Mièville has been Godard’s significant other and major collaborator since 1971, so it’s reasonable that Brody discusses her solo forays in filmmaking, especially since Godard has been involved with them in multiple ways. But how much do we need to know about Mièville’s troubled relationship with her daughter? And, more generally, how imperative is it that Brody try to monitor Godard’s libido and sexual activity — something that even an authorized biographer wouldn’t be properly equipped to do? Though he’s adept at pointing out the ways that most of Godard’s early features contain coded references to his relationship with his lead actress, Anna Karina, these observations are too often allowed to dominate. And speaking to legions of people who’ve worked for Godard in various capacities inevitably leads to a lot of dish — so much so, in fact, that the torments of the shifting relationships often threaten to overtake and overdetermine all the other emotions associated with his movies.

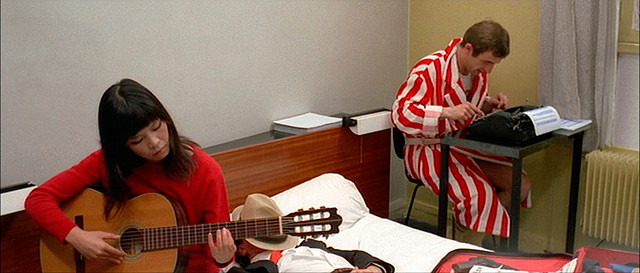

Brody’s biggest gaps in charting this intellectual biography are film history and film criticism. This is especially ironic given the sophistication of his capsule movie reviews for The New Yorker‘s front pages — a savvy often exceeding that of his higher-profile colleagues. Brody is very good at locating the seeds of Godard’s theoretical positions in his earliest criticism and then structuring his book around these conclusions. But he fails to address most of Godard’s major critical work after that, on the page or on the screen. And Brody’s own critical takes on individual Godard films, highly original and frequently provocative, often leave out major elements. I can’t entirely trust a review of Les Carabiniers that fails to mention the staggering, mock-encyclopedic postcard sequence, or an assessment of Made in USA that ignores the thematic and plastic role played in it by animated cartoons — leading to the dubious assertion that “the only images that Godard invested with energy” in the film “are those of Anna Karina.”

Brody is attentive to the paths leading from Masculine Féminin to what he terms “first-person” filmmaking by relative beginners (The Mother and the Whore, Clerks, Slacker, and Go Fish). But when he recounts how Godard destroyed most of the possessions in the flat he shared with Karina during the shooting of A Woman Is a Woman, including all of his clothes, he doesn’t seem aware that this apocalyptic event would inspire the two most memorable scenes in Jacques Rivette’s L’amour fou — although he does bring up Rivette’s little-known role as an extra in Breathless.

Brody is clearly a Godard partisan — ready to defend the intractable Éloge de l’amour (2001) against all comers, and passionately committed to solidarity with Andrew Sarris against Pauline Kael in the ’60s auteurist wars. Yet past a certain point, the cumulative unsympathetic biographical data in this book starts to register like a personal indictment, even when it’s mitigated by intelligent qualifiers. It’s one thing when “new philosopher” Bernard-Henri Lévy tells Brody that Godard is “an anti-Semite who is trying to be cured,” and cites Godard’s abortive project with himself and filmmaker Claude Lanzmann as part of the intended cure. It’s quite another when Brody concludes that, as a political film, Ici et ailleurs (1975) “is a work of propaganda, not inquiry,” sidestepping the possibility that it might conceivably be both.

Given the inordinate amount of material that had to be gathered and processed, some oversights and oversimplifications are inevitable, but some also make for unnecessary confusion. To contend that Akim Tamiroff’s role in Alphaville was largely modeled on his part in Mr. Arkadin sounds shaky if this overlooks his presence in two later Welles films, Touch of Evil and The Trial. When Godard re-edited his Histoire(s) du cinéma in the mid-’90s for home-video release, Brody seems unaware that this was an obligatory move because of rights issues involving some of the clips, and when Godard showed three of its episodes at the Toronto International Film Festival, this was privately and in his hotel room — not publicly, as Brody implies.

On the other hand, it’s fascinating to learn about some of Godard’s wilder casting schemes, such as those involving William Faulkner and Richard Nixon. And overall, the amount of fresh information offered in Everything Is Cinema makes this hefty monument an unfailing page-turner.