This was published in the September-October 1995 issue of Film Comment, as a sidebar to a much longer piece about Edgardo Cozarinsky. — J.R.

Partisan

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

As a member of the FIPRESCI jury at Berlin that gave this year’s Forum prize to Edgardo Cozarinsky’s 68-minute Citizen Langlois, I’d like to quote our citation: “For a brilliant essay revealing a multifaceted grasp of a major pioneer for whom cinema was the ultimate nationality.”

Indeed, at a time when much of what passes for film history is being regulated nationalistically, by state bureaucrats — a process observable in such projects as the British Film Institute’s “A Century of Cinema” series (which stepped off in Berlin with Edgar Reitz’s Night of the Directors), and in the blatantly pro-industry PBS miniseries calling itself American Cinema -– Cozarinsky’s film carries a distinct polemical charge. For Henri Langlois, the unruly and passionate founder/gatekeeper of the Cinémathèque Française spent his life railing against state bureaucracies, and most of his legacy would be unthinkable without this sustained resistance. His eclectic partisanship is more than adequately matched in a personal essay that is as much about exile as Cozarisnky’s One Man’s War and Sunset Boulevards.

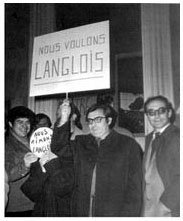

Viewers looking for a comprehensive dossier may be as disappointed as the Gaullist bureaucrats were when they demanded strict accounts and an orderly catalog from Langlois. (Firing him in early 1968 when he failed to meet their demands, they inadvertently launched a worldwide protest that won his reinstatement after demonstrations and brushes with the Paris police that paved the way for May ’68 in more ways than one.) Typically, mad Langlois would pay his staff out of a sack of loose coins from currencies all over the world — one of his many legends. And just as aptly, the international currency expended and celebrated by Cozarinsky is a notion of magpie film collecting and programming spearheaded by Langlois that refuses to honor national boundaries — a utopian notion that incidentally made the French New Wave and Sixties cinephilia as we know it possible. All this may sound frivolous in a country like ours that spends more money on military marching bands than on all other arts combined, and is now gutting its (exclusively U.S.) film preservation program, but even our notion of auteurs may never have come about without Langlois’ fanaticism.

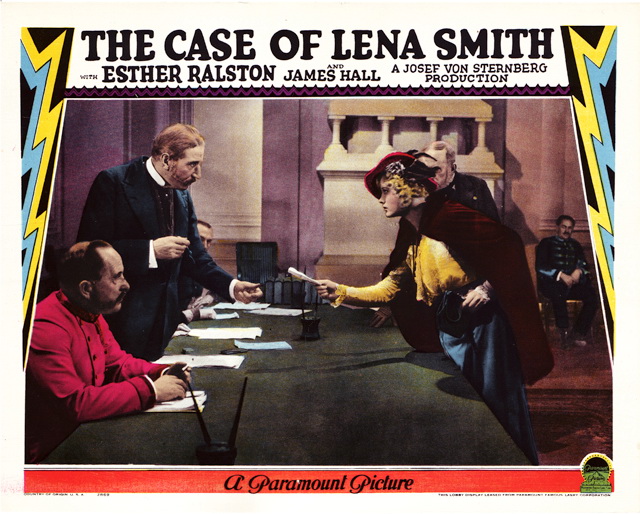

Born in 1914 in Smyrna, Turkey (known today as Izmir), which was occupied by Greek troops four years later, Langlois was forced to flee with his family in 1922 when the Turks reclaimed that enclave, an invasion resulting in fires that destroyed three-fifths of the city. The first shot of Citizen Langlois is of Smyrna in flames, and Cozarinsky views it as a key to Langlois’ character as compulsive archivist –- not so much his “Rosebud” as the furnace consuming the cherished sled. Richard Roud recounts in his Langlois biography, A Passion for Films, that the Langlois family had a suitcase containing all their valuables when they fled, and in the film we hear Langlois describe a recurring dream that haunted his childhood in which he was unsuccessfully trying to save the treasure in a burning city. Film images that burst into flames are one of Citizen Langlois’s motifs,and when towards the end one such occurrence is shown in reverse, the intact image that emerges phoenix-like comes from a lost treasure, later alluded to the film’s wonderful closing line: “Mary Meerson has said, ‘[Josef von Sternberg’s] The Case of Lena Smith will reappear one day when mankind deserves it!'”

Along with Lotte Eisner and Marie Epstein, Meerson is one of the three “women in Henri Langlois’ life” to whom the film pays homage, all of them significantly exiles as well. Thanks to Langlois, the Cinémathèque was less a place than a cause — not simply a stronghold, but an occasion for getting films screened — and this devoted trio were not so much custodians as sisters of mercy in that endeavor.

Aping its subject with its own gathering of disparate materials — the gathering of wedding bouquet in L’Atalante, Jonas Mekas’ film record of Langlois’ reunion with Hans Richter, glimpses of Le Métro (Langlois’ own short film, shot in 1953 with Georges Franju), footage of the New Wave brigade demonstrating on Langlois’ behalf, tributes from such figures as Michel Simon, Lillian Gish, Hitchcock, and Truffaut — Citizen Langlois amply describes the contours of its intertextual subject while steering clear of certain specifics. Not a word is breathed about Langlois’ homosexuality, and aspects of his paranoia are skimped. But the man is there and recognizable. The first glimpse we have of him is already definitive: in his office in the mid-Sixties, he answers the phone to explain that Henri Langlois is out and will be back later in the day.

— Film Comment, September-October 1995