My 1995 liner notes for the Voyager/Criterion laserdisc of Orson Welles’ Othello in its original, untampered-with form. — J.R.

There are two ways of viewing the film career of Orson Welles which have tended, by and large, to be mutually exclusive. One can regard it as a fascinating but largely frustrating attempt to make mainstream Hollywood movies — an effort that yielded one indisputable triumph (Citizen Kane) and five other brilliant if uneven studio releases (The Magnificent Ambersons, The Stranger, The Lady from Shanghai, Macbeth, and Touch of Evil) hampered by dealings with studio management. Or one can regard it as the career of a restless independent making pictures whenever and however he could, a pursuit yielding not only the aforementioned half-dozen features, but seven more — Othello, Mr. Arkadin, The Trial, Chimes at Midnight, The Immortal Story, F for Fake, and Filming Othello, not to mention substantial portions of at least half a dozen unfinished pictures as well.

These two opposing views of Welles’s career were in effect even before he got to Hollywood; in the mid-’30s, he was illegally funneling his sizable earnings as a radio actor into his state-funded stage productions with John Houseman — much as he would later help to finance his own Othello, shot piecemeal and on the run, by concurrently acting in several mainstream pictures that were being made in Europe. By the early 1940s he was already confounding the usual categories not only with Citizen Kane (an independent feature using studio facilities), but also with the abortive It’s All True, which began as a studio project and ended up as an independent one. And in the unfinished and still-unseen The Other Side of the Wind (1970-76), he was staging a no-less unruly shotgun marriage between Hollywood and independent elements, in a story about Hollywood filmmakers made under defiantly independent conditions. Unfortunately, given the resources of the multinational Hollywood apparatus as it exists today, with billions spent annually to promote only Hollywood product, the independent Welles has received scant attention, and is often seen only in relation to Hollywood norms rather than on his own terms.

In the case of Othello, Welles’ first wholly independent feature, one can even speak of two currently available versions of the film corresponding to these two careers, with the differences mainly detectable in their separate soundtracks. The original Othello has the soundtrack recorded and mixed by Welles in Europe between 1949 and 1952. The meticulously revamped version, released in 1992, was a conscious effort to bring this soundtrack more in line with contemporary mainstream tastes and procedures — a process that involved resynching the dialogue to match lip movements more closely (in part by slightly stretching or compressing the durations of individual shots), rerecording an approximation of the original score (as notated and then conducted by Michael Pendowski of the Chicago Symphony), and refashioning the sound effects in a comparable fashion. This enabled the restorers to yield a stereo soundtrack, an option unavailable to Welles.

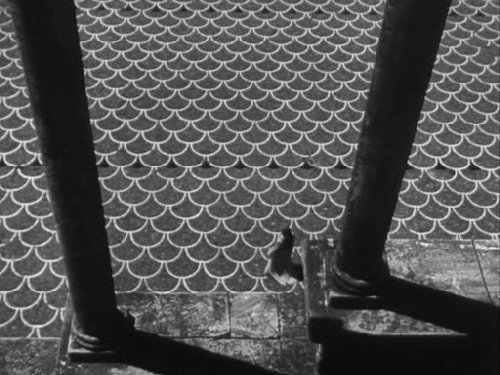

Working on Othello without the resources of Hollywood sound equipment, Welles aimed for a rawness in such sound effects as crashing waves, colliding curtain rings, and echoing footsteps. Drawing from his prodigious radio experience, he partly compensated for his inferior equipment with subtle atmospheric effects dubbed in later and integrated with the music. Welles scholar Ciro Giorgini, who recently interviewed several Othello crew members for an Italian documentary, was told by one of the production assistants that Welles stroked the strings of a piano to achieve a sound effect for the opening sequence and ordered a spinetta, an old form of harmonium, from Florence to produce other effects. Where Lavagnino’s score at one point, according to Welles, used forty mandolins at once, Pendowski’s approximation never used more than three or four. On the other hand, all of the original music composed and scored for Welles by Francesco Lavignino and Alberto Barberis and conducted by Willy Ferraro was recorded with a single microphone, whereas Pendowski had the benefit of modern recording facilities.

The “independent” Othello, which won the Golden Palm at the Cannes Film Festival in 1952 and has long been regarded as a classic in Europe, fared poorly when it opened belatedly in the U.S. in 1955, bringing in only $40,000. Reviewers, perhaps influenced by their Hollywood-trained tastes, tended to compare it unfavorably to Laurence Olivier’s Shakespeare films, finding it amateurish and self-indulgent in relation to the polish and production values of Henry V and Hamlet. Reviewers in 1992 of the refurbished version reacted much more favorably, although the tenor of most of their reviews suggested that the technical differences between the two versions were not clearly understood. Viewers and listeners of this edition — which closely approximates what Europeans saw and heard in 1952 — are invited to judge for themselves.