From the Chicago Reader (March 9, 1990); revised in October 1995 for my collection Movies as Politics. — J.R.

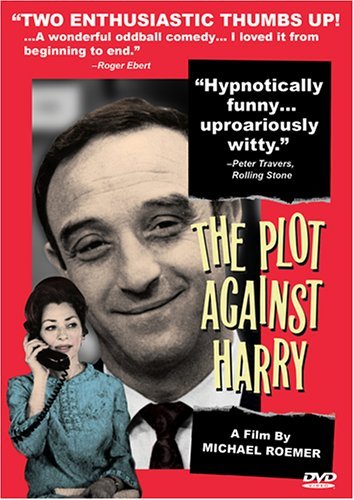

THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY *** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Michael Roemer

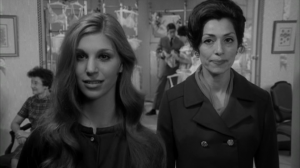

With Martin Priest, Ben Lang, Maxine Woods, Henry Nemo, Jacques Taylor, Jean Leslie, Ellen Herbert, and Sandra Kazan.

I hate stars. There’s a part of our culture that devotes itself ceaselessly to producing, promoting, and consuming them, and a lot of people would have you believe that they rule our consciousness — our politics, our fantasies, our ideas, our conversation, our art and entertainment. But one of our best-kept and most precious secrets is that a great deal goes on in our culture and in our lives that has nothing, absolutely nothing, to do with stars and everything to do with ordinary people.

Insofar as we can distinguish between illusion and reality — and the popularity of someone like Reagan suggests that we neither can nor want to very much — ordinary people, not stars, form the fabric of our daily existence; and most movies, simply by virtue of the fact that they have stars, ignore, deny, and impugn that fabric. An inordinate amount of energy in our society is devoted to proving that stars (Reagan or Bush, Cruise or Streep, Madonna or Jagger, Trump or Warhol, Spielberg or Sontag) are ordinary people just like you and me, when it might be more useful to prove that ordinary people — the people we live with — are the stars that actually belong in our constellations.

“Ordinary people” sounds like a pejorative term, a put-down, but in fact it’s a category of individuals that is infinitely wider and more varied than a category like “stars,” which is narrow to the point of tedium. Yet we act as though stars are as wide as the galaxy (when they’re usually no bigger than TV screens) whereas we consider ourselves small, earthbound, and insignificant — we who can make stars appear or disappear at will, simply by buying tickets or flicking switches or turning our heads.

***

Part of what’s great about THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY, a low-budget black-and-white picture made between 1966 and 1968 and released only this year [1990], is that it has absolutely nothing to do with stars. A star didn’t write it or direct it, and no one resembling a star appears in it. The writer-director, Michael Roemer, a German Jewish refugee, made his first feature at Harvard in 1947, A TOUCH OF THE TIMES — conceivably the first independent feature ever made at an American university, but you won’t find it listed in any film histories, and no one I know has ever seen it. Most of the remainder of his career has been spent in comparable (if occasionally prestigious) anonymity: on numerous documentary crews, as producer and/or director of countless films for public television, as occasional film critic, and, since the early 70s, as professor of film and American studies at Yale. Except for THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY, the only film of his that I’ve seen is NOTHING BUT A MAN, a fiction film about southern blacks that attracted a fair amount of attention in 1964 but hasn’t been revived too often since then.

Roemer criticizes NOTHING BUT A MAN today as narrow and somewhat sentimental, and so it is; but a quarter of a century later, it still towers over the other films of that period (with the exception of Cassavetes’s SHADOWS) by white men about black life: TAKE A GIANT STEP; ONE POTATO, TWO POTATO; BLACK LIKE ME; HURRY SUNDOWN — the list is mainly terrible. NOTHING BUT A MAN, featuring Ivan Dixon and Abbey Lincoln, may not be enough — its approach to its subject is relatively genteel and circumspect — but it’s a long way from terrible.

After the success of NOTHING BUT A MAN, Roemer had a chance to become a star — he was offered several scripts by major studios, most of them about blacks — but he and his longtime collaborator, Robert M. Young (who cowrote, coproduced, and shot NOTHING BUT A MAN), decided to remain independent. Then, in 1966, the Seattle-based conglomerate King Broadcasting offered Roemer complete freedom to make an independent feature of his own choosing and to have final cut on it, and Roemer embarked on the project that became THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY — a comedy influenced by the relatively straight, realistic style of Chicago’s Second City about a not-quite-successful, second-generation Jewish American.

After making a PBS documentary that he and Young were already committed to (FACES OF ISRAEL), Roemer spent a year of research on HARRY that included working as a caterer’s assistant at bar mitzvahs and Jewish weddings on Long Island, following an attorney around Manhattan law courts, investigating the New York numbers racket, interviewing a call girl, and visiting a lingerie showroom. Most of another year was devoted to writing a script (with Roemer and Young regularly and concurrently taking on other jobs to pay the rent), followed by extensive casting carried out by Roemer himself. Martin Priest, a professional who played a small part as a southern bigot in NOTHING BUT A MAN, was cast early on in the lead part of numbers racketeer Harry Plotnick (and a comparison of the two radically different performances reveals that Priest is a consummate pro). But for many of the other parts, Roemer went looking for non- and semiprofessionals, and came up with some remarkable finds, all of them decidedly unstarlike.

For the role of Harry’s former brother-in-law, Leo Perlmutter, who runs a kosher catering business, Roemer found Ben Lang, an auditor for the New York State Department of Labor who had studied acting in the early 50s; many members of the cast are wonderful, but along with Priest, Perlmutter is my personal favorite. For the part of Jack Pomerance, the treasurer of a temple and president of its catering committee, he found a businessman who ran a maid service and acted in his spare time. A songwriter, entertainer, and occasional collaborator with Duke Ellington named Henry Nemo wound up in the part of Harry’s flunky, Max (and it is Nemo’s own song, “Holding On to a Love,” that’s sung on a tacky set by someone behind the wheel of a fake car in the climatic telethon sequence). Harry’s ex-wife, Kay, was played by a psychoanalyst (Maxine Woods), his son-in-law, Mel, was played by a Brooks Brothers salesman (Ronald Coralian), his daughter, Millie, was played by a housewife (Margo Solin); Millie’s fiancé was a cabdriver, Harry’s granddaughter was Roemer’s own daughter, and one of the call girls was played by an actress, Hollis Culver, who is today known as Holly Solomon, owner of the famous Holly Solomon Gallery in Manhattan. Other parts were taken by lawyers,

publicists, and various professional actors (Sally Kirkland is an extra in the telethon sequence, and Zack Norman does a walk-on), including Yiddish stage veterans recruited from an old folks’ home.

After shooting the film in locations all over New York (and in a hotel lobby in New Haven), Roemer edited the film and then screened it a few times for the cast, crew, and friends. No one laughed, many found it hard to follow, and some actively disliked it, so King Broadcasting, with the resigned consent of Roemer — believing he had made a failure — shelved the picture and wrote it off as a tax loss.

About twenty years later, while putting together a complete set of his films on video to give to his children, Roemer was surprised to find the technician in charge of the video transfer laughing uproariously. Belatedly concluding that the film might not be a failure after all, Roemer remixed the sound track, struck a new 35-millimeter print, and halfheartedly submitted the film to both the New York and Toronto film festivals. Both accepted it within the same week.

***

Part of the grace and beauty of THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY stems from the fact that although it has at least three dozen characters and a complicated plot, it glides past the viewer with the greatest of ease. The movie covers what happens over the few days after Harry Plotnick emerges from nine months in prison. The basic tone is comic and satiric, but the comedy and satire almost never take the form of outright gags; they come across as affectionate rather than scathing or malicious — though a wealth of social criticism is implied throughout.

Harry, who is worth about $130,000, finds that he’s getting phased out of the numbers racket by competition, a turn of events spurred by the defection of one of his main operators. As he struggles in vain to regain his foothold, he gets chastised by his parole officer and passes out in the lobby of his hotel; taken to a hospital, he’s told that he has an enlarged heart.

Harry decides to go legit and wants to buy the kosher catering business where his former brother-in-law, Leo, works. The business services a temple and Harry needs to secure the rabbi’s approval of the purchase, so Leo arranges for Harry to be inducted into his lodge, the Mystic Knights of the Sojourners (after Harry donates $2,000 to their children’s hospital), and to appear on a call-in radio show as a reformed racketeer. Then Harry discovers that his books are being audited and that Max, his flunky, has recorded all the payoffs to cops over the past twelve years; Max sets fire to the books and is arrested for arson. Harry collapses a second time in a TV studio during a telethon and, believing that he’s dying, takes the rap for the arson and donates $20,000 to the telethon. Taken to another hospital, he’s told that contrary to his earlier diagnosis he doesn’t have an enlarged heart but an acute case of constipation. About to return to prison for a year, he asks his ex-wife whether she’ll visit him on Sundays, and she shakes her head.

Family gatherings and family-related activities comprise much of the film’s action, as do Harry’s repeated and largely unsuccessful efforts to ingratiate himself with his family — including his older sister, Mae (Ellen Herbert), his former wife, Kay, and his daughters, Margie (Sandra Kazan) and Millie. Implicit throughout most of this is the sense that the respectable society that Harry wants to rejoin is every bit as corrupt and as venal as the rackets, but the film is so intimately acquainted with its chosen milieu that this point never has to be underscored or spelled out in any detail; it’s simply there to be recognized — or not, if the spectator chooses to overlook it. Perhaps the closest the film ever comes to making an ironic commentary (apart from the grotesqueries of the lodge induction, the telethon, and a dog obedience school) is a scene at the home of Margie and Mel, where Harry is being unjustly accused of the arson in the foreground while in the background, on the floor, his granddaughter is looking through a series of nude photos that her father has taken of her mother. Roemer cuts briefly to a closer shot of the granddaughter, but even here there’s nothing strident or obtrusive about the point that’s being made: Roemer simply cuts to a closer shot so we don’t miss what the other characters in the scene are ignoring.

Harry is basically a sad, sweet character, a classic fall guy, but Roemer doesn’t try to sentimentalize him or steer away from his more callous traits; we see him at one point trying to convince a member of a Mafia family to rough up the defector from his organization, and near the end of the film, when he discovers that he’s not about to die, he’s all too willing to take back his telethon donation if he can figure out how to get away with it. For most of the movie, he’s a figure of unbounded generosity, bestowing gifts and favors and money at every turn, but Roemer allows us to see this as both a reflex of Jewish guilt and as a pathetic attempt to win back the affection of his estranged family and associates.

The nonjudgmental tone of the film is part of what makes its very comedy so special and appealing; it is part and parcel of the richness of the world that Roemer depicts, a richness that he refuses to short-change by scoring off easy points against the characters or the milieu. It would be meaningless to call Roemer’s vantage point “objective” — he obviously cares about Harry, for instance — but his skills as a documentarist are everywhere apparent, and they give a kind of depth to his fictional world that makes this movie much closer to the better (and mainly earlier) fiction of Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, and Bernard Malamud than to the star- oriented worlds of Hollywood movies.

***

In the course of attempting to explain why Roemer’s movie took twenty years to reach us, Stuart Klawans theorizes in the Village Voice that Roemer’s elliptical storytelling and his “unwillingness to manipulate the audience . . . merely baffled people who were expecting a comedy,” and adds, “THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY reminds us of a time when Americans had greater material and moral expectations, and less willingness to think their way through a film.”

It’s a nice try, but I think he’s wrong. What “clicks” or doesn’t click with an audience is the result of so many different factors — historical, social, economic, aesthetic, promotional, emotional, intellectual, and simply circumstantial — that I would be reluctant to leap to any conclusions about why THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY didn’t make it into theaters in 1968, or why it did in 1990. Filmmakers, producers, and distributors always depend on a desperate form of guesswork to decide what audiences will like, and who’s to say that Roemer’s movie wouldn’t have been appreciated if it had been released in its own time, in spite of a few bewildered preview audiences? It’s true enough that the passage of time changes our perspective on much of what we see, and the appeal of the movie as a time capsule is not wholly irrelevant to some of the pleasures it affords us today.

But though it may be correct that Americans “had greater material and moral expectations” in 1968, it’s hard to believe that they “had less willingness to think their way through a film.” Some of the films that American audiences thought their way through in 1968 include ACCATONE; BELLE DE JOUR; LES CARABINERS; CHARLIE BUBBLES; CHINA IS NEAR; LA CHINOISE; FACES; LOVE AFFAIR, OR THE CASE OF THE MISSING SWITCHBOARD OPERATOR; PETULIA; TARGETS; 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY; and WEEKEND. It would be dotty to claim that THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY would have presented intellectual, stylistic, or conceptual challenges that were any more arduous than those posed by the dozen movies listed above; on the contrary, one can argue that on certain levels it was and is an easier film to follow and enjoy than any of these others. What is different today, in fact, is that if most of the foreign- language pictures in this list were made last year, they would not have been distributed in the United States at all — distributors would deem them too difficult and esoteric for stateside consumption.

So there’s no particular cause for self-congratulation in the fact that Roemer’s film can reach audiences today. (One shudders to think of how many good films are being kept off the market in 1990.) If there’s a lesson to be learned from this particular case, it’s that being able to see what is right in front of us is seldom a simple matter.

***

Seeing what’s right in front of us is made more difficult by a number of factors in movies, and the usual presence of stars is arguably one of them. Stars tend to command and dominate the spaces they occupy, whether these spaces are made up of other people or settings or props or other objects, and this often means that stars divert our attention from people and things that are equally (or, in some cases, more) worthy of our interest. The absence of stars in THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY allows a vast social universe to take shape before our eyes; if someone like Dustin Hoffman were playing Harry rather than Martin Priest, it’s highly questionable whether we’d be able to see as much of this universe. The issue isn’t whether Hoffman would be “as good” or “better” than Priest but whether his stardom would prevent him from doing anything quite as life-sized — or prevent us from noticing other people and things in the same frames. The sheer existence of movie stars implies that movies are and should be bigger than life, and therefore bigger than us; the absence of stars in THE PLOT AGAINST HARRY makes things more democratic and equitable, closer to our day-to-day existence.