From Omni (September 1983). — J.R.

For a conceptual artist who’s more often concerned with representation than with straight entertainment, Canadian filmmaker Michael Snow can be a pretty jokey fellow. In fact, of all the avant-garde artists I know, he may well be the one who laughs the most and the hardest. His longest and craziest movie — the 260-minute, encyclopedic “Rameau’s Nephew” by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen — contains a grab bag of assorted puns, puzzles, and adages, from lines like “eating is believing” and “hearing is deceiving” to a mad tea party where words and sentences recited backward are then reversed to sound vaguely intelligible. Even “Wilma Schoen” in the title is an anagram for Snow’s name. One of his shortest works, the eight-minute Two Sides to Every Story, is projected on two back-to-back screens, simultaneously showing the same events in the same room from opposite angles.

Just as typical, in the living room of Snow’s house in Toronto, where I recently interviewed him, is a front door that isn’t in use — or rather is in use, but not as a front door. Over the side facing inside the room is a life-size color photograph of a painting of the same door. A concept of a front door in place of a real one? A statement about representation instead of a portal to walk through? Perhaps a bit of both. But there’s another detail in the photograph that makes the whole thing funnier and stranger: a gigantic hand in the foreground holding a lit match. This image is many times larger than life, totally contradicting the supposed equivalence between the real door and the represented door.

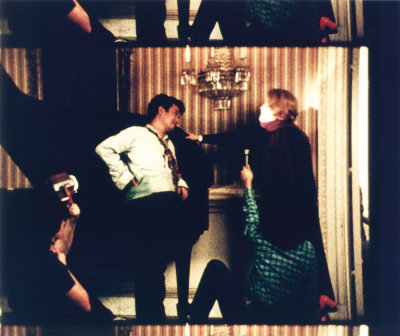

Perceptual and conceptual gags of this kind abound in Snow’s work. Sometimes they’re amazingly literal: After making an epic film trilogy in the late Sixties and early Seventies about possible ways of moving the camera — zooming, panning back and forth, and rotating every which way — he built a set on rollers for a section of another film (Presents, 1981). Then he used a couple of forklifts to jerk the whole flimsy construction to and fro so that the camera wouldn’t have to budge an inch. In the ensuing slapstick mayhem (a needle on a Bach record skips wildly, walls and furniture shake, objects crash to the floor, actors are buffeted about), something about the perception of movement — as well as the intimate relationship between creation and destruction — is being explored.

Just a few short subway stops away from Snow’s house is the best known and most popular of all his works, Flight Stop. It isn’t a movie, but it makes many people think of one. Located in the largest enclosed shopping mall on the continent, Eaton Center, which reportedly attracts more visitors annually than Niagara Falls, this photographic sculpture consists of 60 fiberglass geese, each suspended from three wires and glued to a contoured photograph of a real goose. Extended over about six stories, the geese seem to be landing in formation, and there’s something eerily cinematic about the overall spread, as if each bird were a separate stop-frame in a dispersed simulation of animated flight.

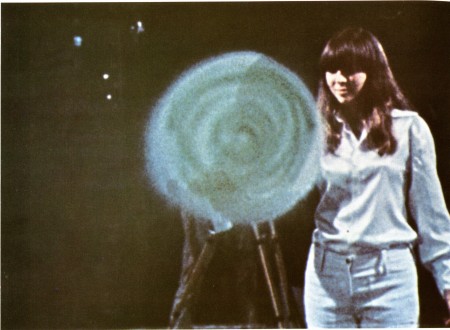

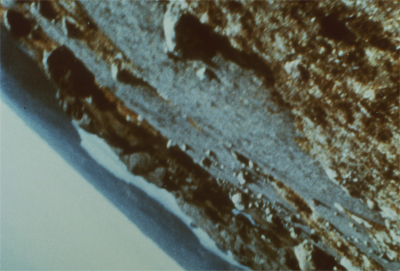

For epic visual breadth, perhaps the only Snow creation to rival Flight Stop is the three-hour film, La Région Centrale (The Central Region, 1971), in which a computer-operated camera spins in endlessly changing configurations around an uninhabited mountain landscape in northern Quebec. It probably wouldn’t be an exaggeration to call this film one of Snow’s least popular works — it certainly has the fewest laughs. But that’s largely because it’s so scary. There’s a direct assault on the senses, including one’s center of gravity, as the flip-flopping camera makes circular patterns at variable speeds that no human being could possibly duplicate, producing an experience roughly akin to riding a demonic ferris wheel. “I wanted to make the film a condensed day,” Snow explained. “It isn’t, really, but it does start in daylight, and then there’s sunset and sunrise, and it’s over at something like eleven.”

In order to make the film, Snow enlisted the help of Montreal technician Pierre Abeloos, who designed a machine that used audio tapes to program the camera’s 360-degree movements without any direct human contact. Then Snow went out looking for a wild location, where nothing man-made was visible, finally settling on an area near Sept-Iles, on the Gulf of St. Lawrence. renting a helicopter, he flew there with three crew members, installed Abeloos’s machine on a remote mountain plateau, and hid from camera range with the others for five cold days in September while the film was being shot.

Why was it so vital to have nothing human either in front of the camera or behind it? “On the one hand, I wanted to have the machine make the film,” Snow told me. “But on the other hand, I wanted to make what you see more yours than the cameraman’s or the director’s, in a way. Even though the height of the camera is the usual human standing height, five feet or so, it makes for a kind of experience that’s not anthropomorphic; it’s an experience that comes explicitly from the machinery.”

“Ultimately,” Snow went on, “the director or the artist is removed just one step in this particular case. Because it is directed. And it is controlled. But the control is not that control of directing your heartstrings. It makes the wilderness yours in one sense, because there’s such a distance between the means of recording it and the kind of thing that the wilderness is. And it also brings into question the whole process of the perception of nature.”

Forever resourceful in reusing material, Snow later remounted Abeloos’s machine in a video-installation piece with four monitors. “The camera goes in the center and you can set it for different patterns. It’s really nice; the National Gallery of Canada bought it. It’s called De là. Obviously it’s a completely different thing from the film, because you get involved in watching the machine move and seeing the kind of drawing that it makes on the monitors, relating the movement to the kinds of images that are produced.”

Something of a prankster and philosopher at the same time, Snow, in his mid-fifties, has a flair for starting off with an unlikely or outrageous idea and somehow making it work. In his first major film (Wavelength, 1967), 40-odd minutes long, he begins with a stuttering camera zoom across an 80-foot Manhattan loft: not much action, as most movies go. but he uses this central concept like a clothesline on which to hang abstract notions about space, time, color, waves, death, storytelling, and representation. (Characteristically, the shooting took him a week and the editing, a couple of weeks, “but I did spend a lot of time musing — a year.”) In Snow’s most recent film (So Is This, 1982), with roughly the same running time, he has the brass to fill his silent screen with nothing but one printed word after another; his imagination and resources keep audiences amused and involved all the way through.

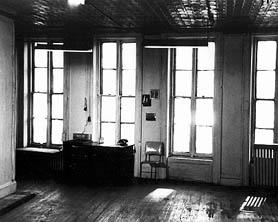

How does he pack so much into so little? In Wavelength, the zoom’s journey across the loft — joined on the soundtrack by a sine wave gradually moving from its lowest note to its highest — starts uneventfully. But as the camera approaches the four double windows and intervening wall space of the other side of the loft, a man is heard breaking into the building and walking upstairs. He staggers into the frame and drops dead on the floor — just before the zoom blithely lurches past him.

Still later, a woman enters, discovers the moribund body, and phones her boyfriend while the camera steadily approaches one of the photographs posted on the central wall space. The photo proves to be a picture of sea waves. The sound of an approaching police siren merges with sine wave, which by now has risen from 50 to 12,000 cycles per second.

As prosaic as all this sounds, Snow has been passing his painterly image through many changes along the way. He uses a variety of color filters, film stocks, superimposed flashbacks of earlier stages in the zoom, and qualities and degrees of processing and light exposure to keep the film moving like a kaleidoscope; yet it seems to be practically standing still. (Many of the same technical variations in Wavelength are used to comparably fluid effect on the single words in So Is This.) In Snow’s elegant description of the movie’s progress, “The space starts at the camera’s — spectator’s — eye, is in the air, then is on the screen, then is within the screen — the mind.” He has also described the film as a “pun on the room-length zoom to the photo of sea waves, through the light waves, and on the sound waves.”

A simpler and wittier forward camera movement defines a 1976 Snow short called either Breakfast or Table Top Dolly. In this case, a camera fronted by a sheet of see-through plastic slowly creeps across a table, converting an artistic still-life of groceries — eggs, orange juice, sugar, Dixie cup, plates, and fruit — into a sticky, gooey mass of garbage while the sounds of dishwashing are heard offscreen. A movie about consumption? If eating is believing and hearing is deceiving, you had better believe it.