Commissioned by the French quarterly Trafic for its 102nd issue (Summer 2017). — J.R.

1. Jarmusch as dialectician

For some time now, Jim Jarmusch has been operating as an

autocritical dialectician in his fictional features. Politically as

well as commercially, The Limits of Control offers a sharp

rebuke to his preceding film, Broken Flowers, by following

Bill Murray as a protagonist — a bored and diffident Don Juan

roaming across the United States to visit four of his former

lovers, in order to discover which one he impregnated with

a son — with Isaach de Bankolé as a protagonist, a hired

assassin in Europe pursuing Bill Murray in the role of Dick

Cheney as he hides out in a bunker until the assassin

finally strangles him with a guitar string. But even more

striking is the radical contrast between Jarmusch’s most

elitist feature (and in many ways my least favorite), Only

Lovers Left Alive, about a romantic, middle-aged married

couple played by Tilda Swinton and Tom Hiddleston —

vampires named Adam and Eve who evoke junkies, rock

stars, and Pre-Raphaelite artists, living on separate

continents in Tangier and Detroit — and Jarmusch’s

most populist feature (and one of my favorites),

Paterson, about a younger romantic couple living together

in Paterson, New Jersey, a bus driver named Paterson

(Adam Driver) who writes poetry in his spare time and a

housewife named Laura (Golshifteh Farahani) who cooks,

specializes in creating black and white décor and clothing,

and is learning to play the guitar.

The dialectical contrast between the last two films goes much

further than the above description implies. Each of the romantic

and mutually devoted married couples in these two films has

a stronger and more dominant partner — the wife (Swinton) in

Only Lovers Left Alive, the husband (Driver) in Paterson —

who’s focused on literature while her or his partner is more

involved with music and plays the guitar. (Consequently, those

American critics, myself included, who have complained that

the wife in Paterson is treated somewhat condescendingly as

an artist who fetishizes black and white have conveniently

overlooked that a similar charge could be lodged against the

narcissistic, childish, and even more self-absorbed husband

in Only Lovers Left Alive.) The characters in the first film

are split between stars and/or performing artists on the one

hand (Adam, Eve, Christopher Marlowe, a Lebanese singer)

and devoted groupies, fans, and assistants on the other;

most of the stars are vampires and most of the others are

defined (or at least described) as “zombies”, whereas all

the characters in the second film are perceived as social

and cultural equals and all of them could be described

as creative artists of one kind or another, whether they

know it or not (This includes even a hapless, lovelorn

suitor named Everett who threatens to shoot himself

with a toy gun, staging a violent crisis in a bar; and

even the married couple’s bulldog, Marvin, qualifies

as a punk artist of sorts when he shreds the notebook

of Adam containing all of his handwritten poetry.) The

only “stars” evoked in Paterson are a few local

celebrities, living (Iggy Pop) and dead (Lou Costello,

Allen Ginsberg), whose photographs decorate the

walls of a mainly black bar that Paterson frequents

when he walks his dog.

2. Jarmusch as minimalist

“I think the world has enough chaos to keep it going for the

minute,” Christopher Marlowe (John Hurt) declares to Eve

in Tangier—a statement that recalls a repeated statement

in The Limits of Control, “The universe has no center and

no edges.” Both of these somewhat terrified statements

appear to motivate Jarmusch’s carefully sustained and

articulated minimalism as a calculated gesture against

chaos, even though Marlowe himself, depicted here as the

pseudonymous author of Hamlet, is hardly any sort of

minimalist himself, any more than William Carlos

Williams, the implied resident guru-poet of Paterson, is,

especially in the sprawling and Whitmanesque book-

length poem that gives the film its title.

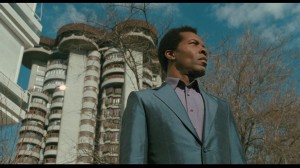

Even the nameless minimalist hero-protagonist of The Limits

of Control, played by Isaach de Bankolé — as centered and as

edgy as Lee Marvin in Point Blank, one of Jarmusch’s likely

reference points, whose simple directness is offered as a salutary

corrective to faceless multicorporate corruption — is a bit of a

dilettante when it comes to appreciating art at Madrid’s Museo

Reina Sofia or flamenco dancing at a bar in Seville. The same

applies to Forest Whitaker’s Ghost Dog, an earlier version of

a minimalist black hitman, with his taste for literature that

highlights multiplicity and complexity — The Wind in the

Willows, The Souls of Black Folk, Rashomon, Frankenstein

— as well as his more minimalist guidebook, Hagakure or

The Way of the Samurai.

Yet it’s part of the beauty and power of Jarmusch’s

minimalism as he’s developed it in Paterson that it seems

bountiful rather than deprived, an embarrassment of

everyday miracles that yields an exquisitely uncluttered

film about commonplace clutter — the kind that accumulates

during a mainly ordinary week in the life of a New Jersey bus

driver who also writes poetry, and one in which the ordinary

flow of time is given an uncommon degree of orchestration:

varying degrees of slow or fast motion — the hero’s loping

walk, the rushing second-hand of his wristwatch–

superimposed over images of his poems as they’re being

slowly composed or recomposed, word by word on screen,

and his lyrical reveries about cherished people and places,

which periodically evoke the Vigo of L’Atalante.

3. Jarmusch as fantasist

Like Leos Carax, Jarmusch is a filmmaker of romantic and

poetic fantasy conceits in which a certain nostalgie de la boue

always plays a part. But unlike Carax, Jarmusch’s sense of

fantasy is always grounded in at least a superficial sense of

banal reality; even his century-old vampires occupy the

recognizably mundane quarters of Detroit and Tangier.

Paterson is of course less obvious as a fantasy than Only

Lovers Left Alive, yet its utopian vision of small-town

America as a friendly multiracial community in which

every person appears to be some sort of artist is clearly

sustainable only as a defiant poetic conceit that flies in

the face of a Trump-led America, however gentle its

multiple articulations might be. Furthermore, the

preponderance of twins who keep turning up in

Paterson, New Jersey is as fanciful as the abnormal

and logically unjustifiable number of dog reaction

shots in the film assigned to Marvin (anticipated by

the dog reaction shots in Ghost Dog: The Way of

the Samurai).

There’s a particular moment about halfway through Ghost Dog

when Jarmusch’s strength and confidence as a fantasist

intersect with his instincts as a poet. After Ghost Dog’s rooftop

home is destroyed by Italian gangsters, he sends them a

message by carrier pigeon that’s a quote from Hagakure,

read aloud by Sonny Valerio (Cliff Gorman): “’If a samurai’s

head were to suddenly be cut off, he’d still be able to perform

one more action with certainty.’…What the fuck is that

supposed to mean?” “It’s poetry,” explains Ray Vargo

(Henry Silva). “The poetry of war.” The sheer improbability

and outlandishness of both the homing pigeon and this

understanding of poetry from a New Jersey gangster

is quintessential Jarmusch, as mannerist as a character

in a Faulkner novel speaking the same way that Faulkner

writes.

4. Jarmusch as traditionalist

In many of his previous features, Jarmusch has offered his own

eccentric versions of commercial film genres: Western (Dead

Man), hitman thriller (Ghost Dog), James Bondish spy thriller

(The Limits of Control), and horror film (Only Lovers Left

Alive). Paterson departs from this pattern by suggesting that

ordinary American lives and traditions provide the only formal

guidance needed. It’s a form of artistic maturity that suggests

that even though Jarmusch is technically a paying member of

the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, he is far too

independent and far too “East Coast” as a filmmaker to qualify

for an Oscar anytime soon.

5. Jarmusch as formalist

One of the more mysterious aspects of Paterson is whether the

form creates the content or the content suggests the form. A

good example of this question can be Franz Kafka’s “Blumfeld,

an Elderly Bachelor.” The first part of this story recounts a

comic fantasy: the grumpy title hero comes home to his sixth-

floor walk-up, and “two small white celluloid balls with blue

stripes” begin playfully following him around the room,

coordinating their moves with his and with each other’s. They

bounce after him for the remainder of the evening, and then

resume their teasing play in the morning — until he lures

them into his wardrobe and locks them inside. The second

half of the story prosaically recounts his dull morning at the

linen factory where he works, dominated by his irritation

with the two assistants who share his tiny office. This story

is remarkable not just for the fantasy that precedes the

depiction of everyday normality, but for the playful form

itself — the subtle and disquieting rhyming of the bouncing

balls with the two assistants. One wonders whether Kafka’s

concept began with the bouncing balls, the assistants, or the

echoes between the two.

There’s a similar ambiguity in many of the playful two-part

inventions of Coffee and Cigarettes. The second episode,

“Twins,” features Joie and Cinqué Lee, two of Spike Lee’s

siblings, playing twins (which they’re not in real life); their

petty bickering consists mainly of each contradicting and

echoing the other. Their dialogue with a waiter concerns

the legendary twin of Elvis Presley who died at birth and

the siblings’ charge that Elvis ripped off the music of black

musicians such as Otis Blackwell and Junior Parker

(another form of duplication). Then, five episodes later,

we get “Cousins” — a playing out of the elitist versus

egalitarian dialectic that later figures between Only

Lovers Left Alive and Paterson — in which Cate

Blanchett, within the same shots, plays both herself

(a movie star) and her (fictional) punk cousin Shelly,

seething with jealous resentment when Cate meets

her in the lobby of her luxury hotel. This is followed

first by a sketch featuring musicians Jack and Meg

White, a former couple who pose as siblings, then by

“Cousins?” — in which Alfred Molina and Steve Coogan,

meeting for tea in Los Angeles, play in a variation on the

Blanchett episode that hinges on whether these two

actors might be cousins — and, finally, by “Delirium,”

in which two other musicians, GZA and RZA, both

members of the Wu-Tang Clan (which provided the

score for Ghost Dog), introduce themselves to Bill

Murray as cousins.

The principal formal structure of Paterson is the

seven days of the week and all the daily rituals

contained in that structure (see #6, below).

Whereas the more common way of viewing such

rituals and repetitions is to view them as boring

and tedious, both Paterson and Paterson find

them pleasurable and comforting — that is to say,

musical.

6. Jarmusch as musician

As much a musician as a poet, Jarmusch is also partially

responsible for Paterson’s score, as a member of the three-person

rock band Sqürl consisting of himself, Carter Logan (Jarmusch’s

coproducer since The Limits of Control) and musical engineer

and music producer Shane Stoneback. But more generally, his

musical temperament can be felt in the numerous repetitions,

thematic variations of verbal and visual motifs, and “rhyming”

shots that abound in his films. In The Limits of Control,

virtually everyone who meets Isaach de Bankolé’s character

begins by asking him, “You don’t speak Spanish, right?”; this

usually happens in Spanish cafés where he habitually orders

two expressos, and he also exchanges match boxes with most

of the people he meets. A repeated epigram in the same film:

“Those who think they’re bigger than the rest should go to the

cemetery. There they will see what life really is: it’s a handful

of dirt.”

There are also motifs that recur in separate Jarmusch features,

such as guitars, twins (a preoccupation in his sketch feature,

Coffee and Cigarettes), and match boxes (the subject of one

of Paterson’s poems), and sometimes the same actors (Isaach

de Bankolé, John Hurt, Tilda Swinton). Paterson is constructed

around the repetitions and/or variations of motifs that occur

over a single week, starting with the sleeping or waking positions

of Paterson and Laura as each day begins, the time on Paterson’s

wrist watch that he observes just before he puts it on, the Cheerios

he has for breakfast in the kitchen, and countless other daily

rituals, including his walk to work, the habitual complaints of his

Latino boss about his own troubles at home, Paterson’s bus route,

his checking the mailbox in front of his house when he returns

home (sometimes correcting its bent position, which we eventually

discover is due to Marvin), his walking the dog, his tying of

Marvin’s leash around a pipe before entering the bar, etc. And I’ve

already mentioned the strange proliferations of twins and dog

reaction shots.

7. Jarmusch as poet

Jarmusch studied poetry at Columbia University with New

York School poets Kenneth Koch and David Shapiro, and

reportedly has written some poetry as well, but only one of the

poems heard and seen in Paterson was written by him — “Water

Falls,” attributed to a ten-year-old girl whom Paterson meets

by chance while walking home and who reads it aloud to him.

All the other poems in the film, apart from William Carlos

Williams’ “This is Just to Say” (read by Paterson to his wife) and

some rapper poetry recited in a laundromat, were written by

Ron Padgett (another New York School poet) — four pre-existing

poems and three others written for the film, all seven attributed

to Paterson.

In many respects, Paterson is more concerned with the activity

of writing poems than it is with the social functions of poems as

cultural objects, and Jarmusch’s preoccupation with his hero’s

creative processes is central to his focus on all the other people

in Paterson whom he encounters or (as a bus driver) overhears

among his passengers. All these people are viewed as artistically

creative in one way or another, but without the egotism or

ambition or desire for fame that we often associate with artists.

This is especially true of Paterson himself; his wife chides him

for not making copies of his poems, which exist only in his notebook,

and there’s no evidence that he has any desire to publish them.

After Marvin shreds his notebook, Paterson, during a conversation

with a Japanese poet whom he meets by chance, even denies being

a poet himself, insisting that he’s only a bus driver. But after the

Japanese poet gives him an empty notebook as a parting gift, one

feels that he has once again accepted “poet” as part of his identity.

In a 1996 interview that I once had with Jarmusch, we had the following exchange:

Rosenbaum: In a recent essay about the dumbing down of American movies, Phillip Lopate writes, “Take Jim Jarmusch: a very gifted, intelligent filmmaker, who studied poetry at Columbia, yet he makes movie after movie about low-lifes who get smashed every night, make pilgrimages to Memphis where they are visited by Elvis’s ghost, shoot off guns and in general comport themselves in a somnambulistic, inarticulate, unconscious manner.”

Jarmusch: I don’t know, man. Once I was in a working-class restaurant in Rome with Roberto [Begnini] at lunchtime. They had long tables where you sit with other people. We sat down with these people in their blue work overalls, they were working in the street outside, and Roberto’s talking to them, and talking about Dante and Ariosto and twentieth-century Italian poets. Now, you go out to fucking Wyoming and go in a bar and mention the word poetry, and you’ll get a gun stuck up your ass.That’s the way America is. Whereas even guys who work in the street collecting garbage in Paris love nineteenth-century painting.

Like many of the details in Paterson, this suggests

that the evidence of almost nonstop artistic creativity

that one witnesses in Paterson, New Jersey is neither

plausible nor realistic but a poetic and utopian vision

about what the town might be — or perhaps what it

already is, hidden under the surface, or maybe also

what it once was (given the film’s implicit but

omnipresent sense of nostalgia), before diverse

middle-class and capitalist anti-art reflexes hid it

from view.

To a large degree, this is what makes the film’s poetic vision so

precious: the sense that America as a community of friendly

artists is not so much an impossibility as a transcendental

potentiality, buried just beneath the surface of everyday

activities — a “lost America” that conceivably could be found

again, much as Paterson himself temporarily loses and then

rediscovers it. In this respect, Paterson is the precise,

dialectical opposite of my other favorite Jarmusch feature,

Dead Man, where not even an accountant named William

Blake (Johnny Depp) understands the significance of his

name, which is understood and appreciated only by a Native

American who is himself labeled by his fellow tribesmen

as Nobody.