From the Chicago Reader (December 4, 1998). — J.R.

The Sentinel

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Arnaud Desplechin

Written by Desplechin, Pascale Ferran, Noemie Lvovsky, and Emmanuel Salinger

With Salinger, Thibault de Montalembert, Jean-Louis Richard, Valerie Dreville, Marianne Denicourt, Bruno Todeschini, and Laszlo Szabo.

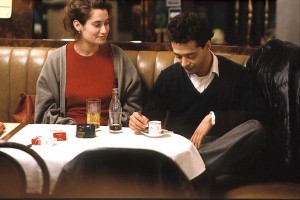

Anyone who saw the three-hour My Sex Life…or How I Got Into an Argument (1997) when it showed at the Film Center last year knows that, for better and for worse, writer-director Arnaud Desplechin, born in 1960, has a generational voice, speaking for and about French yuppies in their late 20s and early 30s. The same is true of his only previous feature, The Sentinel (1992), an eerie 139-minute espionage thriller that has been accruing a cult reputation here and abroad (it’s playing this week as part of Facets Multimedia’s New French Cinema Film Festival). My Sex Life, for all its virtues, was a bit conventional and bland, but The Sentinel is genuinely crazy and a lot more interesting, mainly because it has a meatier subject: the end of the cold war and what this means to French yuppies.

“French yuppies” sounds condescending, but a lot more than the Atlantic Ocean separates Americans from the worldview of the French. It’s been a long time since we’ve lived through a foreign invasion or occupation, and the sheer size of our country, like the size of Russia or China, deprives us of the more international perspective Europeans have.

“We live on top of a billion corpses,” says Mathias (Emmanuel Salinger), the hero of The Sentinel. “It’s as if we spit on them. We want to forget them.” He’s speaking about the casualties of the cold war, but he doesn’t use “we” the way Americans would, even when discussing the cold war. For one thing, he includes other Europeans and perhaps even Americans; when we say “we” we mean only Americans. (Case in point: A recent editorial in the Nation reports that UN sanctions against Iraq cause up to 7,000 infant deaths a month. This implies that “experts” have decided that writing off this many babies is necessary to achieve a “healthier” situation in the Middle East, though if someone reached that conclusion about 7,000 American babies a month for the greater good of North America, we might pause a little longer. Of course when the French say “we” they aren’t including Iraqis either.)

There’s a more global use of “we” in Jacques Rivette’s first feature, Paris Belongs to Us, made 40 years ago in the depths of the cold war; the tragedies that film alludes to include the communist invasion of Hungary as well as the blacklist that turned some Americans into exiles. Indeed, part of what kept me interested in The Sentinel was all the ways it echoes and contradicts the despairing paranoia of Rivette’s film. I was especially intrigued by all the changes both films ring on the meaning of “we” and “us,” beginning with Rivette’s beautiful title.

Both films are structured around interlocking but separate groups of young people in Paris, who are connected by a central character on an obsessional quest. In Paris Anne is a naive Sorbonne dropout looking for an “apocalyptic” recording of guitar music by a Spanish exile who killed himself for unknown reasons, music she wants to contribute to an ambitious but underfunded stage production of Shakespeare’s Pericles. In The Sentinel Mathias, who’s less naive — the son of a deceased French diplomat in Germany who comes to Paris to study forensic medicine — discovers that someone has put a man’s severed head in one of his suitcases, and he spends most of the remainder of the film trying to discover who the man was.

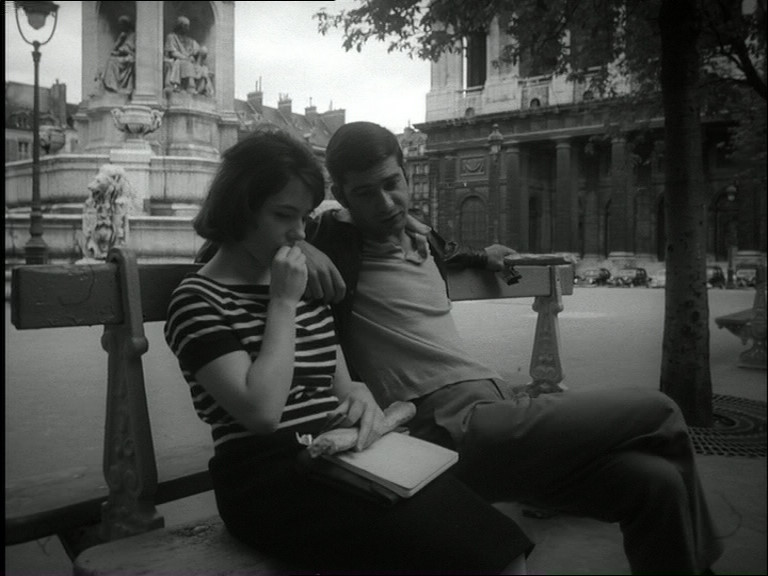

Both quests intersect with art as well as politics (The Sentinel adds science to the mix): Mathias’ sister Marie (Marianne Denicourt) is seen rehearsing classical songs, and his sometime girlfriend studies art history — rough parallels to the characters who have theater rehearsals in Rivette’s film. (Both films also highlight extended quotations from Shakespeare in English: The Tempest in Paris, Hamlet in The Sentinel.) Both heroes encounter corruption on both sides of the cold war and become increasingly implicated in the intrigues and counterintrigues and increasingly angry about their largely unwitting involvement. Yet in striking contrast to the familiar poetic Paris encountered by Rivette’s characters, Desplechin offers a Paris drained of lyricism and historical nuance, with little atmosphere — only a succession of colorless interiors and exteriors.

Is this because Desplechin wants to comment on the drabness of the present, or is it because he has no lyricism of his own? How much is because of the class difference between Rivette’s bohemians and Desplechin’s yuppies? It’s creepy but characteristic that this movie becomes most energized when Mathias is alone with the severed head — an amazingly convincing prop that, as some French critics have noted, is used in relation to the mystery plot the way the photograph is used in Blowup. The Sentinel also does a lot with the metaphorical relationship between making surgical incisions and defining national borders — it opens with an account of Churchill and Stalin in Yalta cynically slicing up eastern Europe — yet when it comes to creating a multinational milieu, which Paris Belongs to Us evokes so well, it seems stranded in a no-man’s-land that seems French by default. Paradoxically its hero seems starved for the kind of metaphysics that menaced the characters in Rivette’s film; without a clear system of good and evil — which one character associates with Cain and Abel — even difficult moral decisions seem to rule out the world at large.

A few Russian characters turn up in the plot, including a Russian Orthodox priest, and much is made of the Jewishness of one of Mathias’ fellow interns. But no Americans or Germans of any consequence figure in the story, and only a couple of familiar French character actors — Jean-Louis Richard and Laszlo Szabo — link the milieus of this film to an older France. In other words, Desplechin has cultivated a historical and geographical conscience that we’re unlikely to find in an American movie, but his remoteness from the lived experience of those vast reaches is part of what this thriller is ultimately concerned with. Like the terse and quasi-abstract chapter headings that structure the narrative–titles such as “remorse,” “the ambassadors,” “my best enemy,” and “lone rider” — The Sentinel is limited as well as defined by an overall sense of being stranded, suggesting that the cold war, for all its horrors, offered a sense of time and place that younger generations no longer find accessible.