From the Chicago Reader (December 11, 1992); also reprinted in Movies as Politics. — J.R.

MALCOLM X

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Spike Lee

Written by Arnold Perl and Spike Lee

With Denzel Washington, Angela Bassett, Albert Hall, Al Freeman Jr., Delroy Lindo, and Spike Lee.

“At the top of 1968, over the vehement protests of my family and my friends, I flew to Hollywood to write the screenplay for The Autobiography of Malcolm X. My family and my friends were entirely right; but I was not (since I survived it) entirely wrong. Still, I think that I would rather be horsewhipped, or incarcerated in the forthright bedlam of Bellevue, than repeat the adventure — not, luckily, that I will ever be allowed to repeat it: it is not an adventure which one permits a friend, or brother, to attempt to survive twice. It was a gamble which I knew I might lose, and which I lost — a very bad day at the races: but I learned something.” — James Baldwin, The Devil Finds Work (1976)

“If the complexity that was Malcolm X survives this moment as only a T-shirt or a trademark, then it is no wonder that Clarence Thomas has emerged as the perfect cooptive successor–an heir-transparent, a product with real producers; the new improved apparition of Malcolm, the cleaned-up version of what he could have been with a good strong grandfather figure to set him right. Clarence X gone good.

“Clarence Thomas is to Malcolm X what ‘Unforgettable. The perfume. By Revlon’ is to Nat King Cole. A sea change of intriguing dimension, like when Eldridge Cleaver came back from Algeria preaching the good news of free enterprise and started marketing trousers with codpieces and barbecue sauce. Or when Ray Charles proclaimed that, while he sang ‘America the Beautiful’ at the 1988 Republican National Convention, he would have done it for the Democrats ‘if they had paid me some money. I’m just telling the truth.'” — Patricia J. Williams in Malcolm X: In Our Own Image (1992)

Both of these quotations help to show how and why, given what we all have to work with — three decades of mythmaking and contradictory appropriations; tons of shameless Spike Lee hype and shamefaced white guilt converging in ecstatic interface; miles of media jive and ancillary products devoted to black pride and manhood and inner-city role models — there’s no possible way that Malcolm X could be completely accurate and truthful. Let’s be real: the fact that this movie exists at all automatically overwhelms almost anything that might be said about it.

“Malcolm constitutes the quintessential unfinished text,” notes Marlon Riggs in Malcolm X: In Our Own Image — an excellent recent collection edited by Joe Wood, that is already cited above. “He is a text that we, as Black people, can finish, that we can write the ending for, that we can give closure to — or reopen — depending on our own psychic and social needs.” Considering the diverse passions and biases reflected in the 15 black contributors to this book, it is easy enough to see what Riggs means, and not at all easy for a white writer like myself to feel like a legitimate voice in this debate.

But the root difficulties of coming to some kind of terms with Malcolm X in 1992 are still plainly shared by everyone. If James Baldwin’s lost gamble has improbably mutated into Spike Lee’s bluff and triumph, extenuating circumstances and interfering noise prevent us from thinking straight about it: there are simply too many interests to be placated, prejudices to be honored and exercised, euphemisms and compromises (and sometimes lies) to be glossed over, heated emotions to be respected, feathers unruffled, industry palms greased. If you genuinely believe that there’s no contradiction in making an Oscar-lusting movie with big-studio backing and wanting to tell the unvarnished truth about Malcolm X — if, in other words, Baldwin is wrong and Lee is right — then I can only say that Warners has done an even better job than usual of selling you the Brooklyn Bridge with butter-flavored cholesterol sprayed all over it.

Lee dramatizes the fusion of — and confusion between — business and art better than any other American filmmaker who comes to mind. I certainly don’t begrudge him his marketing talent, including selling “Malcolm” products to white kids on Melrose Avenue in LA: he’s not doing anything the big corporations wouldn’t. When he inherits the talented Denzel Washington as his star from a package previously assembled for director Norman Jewison — an actor who seems too handsome, too dark-skinned, and too elegant for the part — I can sympathize and wish him well. (Larry Fishburne, for one, would almost certainly have been better casting.) Or when Lee calls Warner Brothers a plantation while clamoring for a higher budget and doing everything he can to emulate and imitate JFK, I can both see what he means and appreciate his ability to milk the press, the studio, and the audience at the same time. (He may be no David Lean, but there are times when his show-biz religiosity and his total lack of self-consciousness remind me of Cecil B. De Mille.) I can even understand, if not exactly appreciate, the reasons he occasionally conflates himself with Malcolm X as a controversial outspoken figure, apparently regarding his own life at times as a similar process of getting from one damned press conference to the next.

But when Lee manages his art by choice like a boorish and aggressive businessman, with seeming indifference to the aesthetic consequences, I start to have doubts. When he begins his movie with a speech by Malcolm X and clips of the Rodney King video and shots of an American flag burning down to an X and a full serving of Terence Blanchard’s overloaded score, all delivered more or less at once and at full blast, I’m forced to conclude that he doesn’t respect any of these ingredients enough to allow them to be heard or seen with close attention — which is another way of saying that he doesn’t really respect his audience either. Later in the film, he offers a comparable MTV fruit salad of another Malcolm X speech, shots of Malcolm thinking (as if to remind us briefly of what he won’t let us do ourselves), John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” and archival footage of Martin Luther King and police violence during the civil rights movement.

Like someone wearing a belt and suspenders at the same time, Lee doesn’t want to leave anything to chance — he avoids silence (the ultimate taboo) in all his films — so the very idea of being able to listen briefly to the beautiful “Alabama” as opposed to being sprayed with it by a fire hose never comes up. One would like to think that Lee would be capable of presenting Malcolm X’s various messages without feeling obliged to advertise them, along with the caps and T-shirts.

A postmodernist Brooklyn provincial, Lee tends to lose his bearings whenever he strays very far from the present and his home turf — one reason why Do the Right Thing, which sticks to a single block of Bed-Stuy over one recent summer day, remains his best movie. When he settles on what he knows, both a world and characters come into view, even if they’re perceived through a miasma of wallpaper music and endless show-off camera moves. When he doesn’t know as much about what he’s filming, the empty technique and the salad dressing take over, ejecting us from his material and straight into the Spike mystique, which is strictly business, not art. This is undoubtedly why the first hour or so of Malcolm X — set mainly during the early 40s in Boston and Harlem, with brief flashbacks to Michigan — probably contains the least reality of any Lee feature to date, although there are plenty of fancy zoot suits and glitzy crane shots to distract us from the overall lack of conviction.

To be fair, the movie does have a visual plan built around various uses of black and white: check out, among other things, cinematographer Ernest Dickerson’s interesting and inventive uses of blinding sunlight in the opening Roxbury sequence, absolute darkness when Malcolm is in solitary confinement, and the black-and-white stripes of light through a venetian blind when Malcolm confronts Elijah Muhammad about his sexual transgressions. But the possibility of finding or creating any recognizable sort of social reality in Roxbury or Harlem in the 40s, apart from images in other bad movies, seems not only beyond Lee’s range but beyond his comprehension or interest.

Consider Roxbury’s Roseland Ballroom, where Malcolm Little, then known as “Red,” worked for a time as a shoeshine boy, and which takes up about ten pages in the Autobiography. This pungent section inspired one of the giddiest flights of fancy in the novel Gravity’s Rainbow, but it’s hard to know how this richly evoked world could have been captured on film, even if Lee had devoted a whole feature to it. Any hope that this world or a shadow of it would make it to the screen was immediately jettisoned once Lee opted for a musical comedy production number in this setting.

It’s a move clearly designed to show us only what Lee can do; all it can do for the Roseland or Malcolm X’s life at this point is to trivialize them and make them more remote, even with a Lionel Hampton look-alike leading the band. So it’s irrelevant to note that this sequence improves on the production numbers in School Daze — unless we decide, as some critics apparently have, that Lee’s career rather than Malcolm X’s life should be the key reference point of this movie.

Fortunately, the movie gets much better once its hero lands in prison, and ideas and rhetoric — most of it supplied by the Autobiography — fill in some of the various cavities in the screen left by the period, settings, and characters. As soon as Malcolm finds a language and a new surname to go with his first pair of glasses, the movie acquires a voice, and even though Lee rarely allows this voice to speak more than sound bites, it still has plenty to say. And toward the end of the film, when Lee arrives at the assassination, he finally achieves some of the filmmaking power that his flashy technique has been striving for, wedded for once to his subject matter.

Considering all the gaps, ambiguities, and contradictions that continue to circulate around Malcolm’s life and death, it probably shouldn’t be too surprising that there are almost as many mysteries surrounding the history of this movie’s script. According to Lee in By Any Means Necessary, his latest thrown-together movie tie-in book, “[James] Baldwin wrote the first script. At the time he was really drinking heavily, and eventually another writer named Arnold Perl helped him finish it.” The way that Lee casually throws in a reference to Baldwin’s drinking is characteristically unreflective and ungenerous; I’m not aware that Baldwin, heavy drinker or not, needed collaborators to help “finish” any of the articles or books he wrote over the same period.

Perl, a TV writer, playwright (The World of Sholem Aleichem), and occasional screenwriter (Cotton Comes to Harlem), was blacklisted during the McCarthy era and died in 1971. According to a friend of his whom I recently spoke to, Perl had already written his own screen adaptation of Malcolm X’s autobiography before Baldwin was hired by Columbia Pictures. He subsequently wrote and produced The Documentary of Malcolm X, nominated for an Oscar in 1972.

And according to Baldwin in The Devil Finds Work, who never mentions Perl by name, “Near the end of my Hollywood sentence, the studio assigned me a ‘technical’ expert, who was, in fact, to act as my collaborator. . . . Each week, I would deliver two or three scenes, which he would take home, breaking them — translating them — into cinematic language, shot by shot, camera angle by camera angle. This seemed to me a somewhat strangling way to make a film. . . . As the weeks wore on, and my scenes were returned to me, ‘translated,’ it began to be despairingly clear (to me) that all meaning was being siphoned out of them.”

Baldwin then describes a key instance of this — a short scene set in Small’s Paradise in Harlem in which Malcolm, still fresh from the country, first meets West Indian Archie, “the numbers man who introduced Malcolm to the rackets.” In Baldwin’s version, while Malcolm orders a drink at the bar, Archie and his friends, sitting at a nearby table, make jokes about his naivete while obliquely acknowledging that they all used to be like him themselves; then, after Malcolm stumbles over Archie’s shoes, Archie invites him to sit down at his table. In Perl’s version, Baldwin reports, Malcolm’s stumbling over Archie’s shoes precipitated an angry showdown — “a shoot-out from High Noon, with everybody in the bar taking bets as to who will draw first.” The studio approved this expansion, and Baldwin, patiently explaining the irrelevance to reality and common sense of such a scene, explains how, after he saw what was being done to his work by both Perl and the studio, he eventually “walked out, taking my original script with me.”

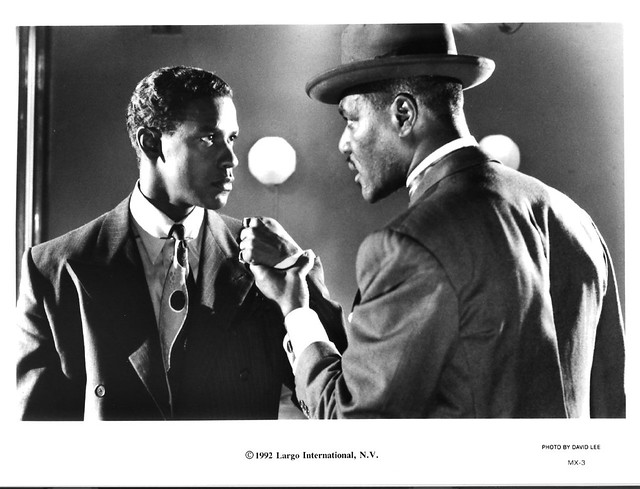

That script, entitled One Day, When I Was Lost, was published 20 years ago and recently reprinted. Lee never mentions it or any of Baldwin’s dissatisfactions with what was done to it in By Any Means Necessary, which includes the fourth draft of the script he used, credited to Baldwin, Perl, and himself, in that order. The final movie, which differs from this fourth draft in many respects, credits only Perl and Lee because Baldwin’s sister Gloria, the executor of his estate, asked that her brother’s name be removed. It’s easy to sympathize with her decision; as the scene in Small’s Paradise now unfolds, Perl’s High Noon showdown is made to look like social realism. A big bully collides with Malcolm at the bar, derides him for not saying “Excuse me,” calls him an “old country nigger,” knocks off his hat, and adds, “What’s you gonna do? Run home to your mama?” Malcolm grabs a whiskey bottle, smashes it to smithereens against the guy’s jaw, and says, “Don’t you ever in your life say anything against my mama.” Then he retrieves his hat from a pretty and adoring woman at the bar, tenderly caresses her cheek, and orders a whiskey. Archie (Delroy Lindo) at his table in the next room is so awed by all this that he quickly contrives to buy Malcolm’s drink. It’s a quintessential Oscar-movie moment — complete with macho childishness, violent excess, and a comfortable indifference to history, setting, and character. If Baldwin’s name were still on the picture, he’d undoubtedly be spinning in his grave.

Structured rather like an Alain Resnais film, and therefore anything but Oscar-ready, One Day, When I Was Lost is a poetic, personal reading of the Autobiography that, as Terrence Rafferty has remarked in the New Yorker, “plays beautifully in the reader’s mind” — a work that Perl and Lee have successively plundered in order to yield something unpoetic, impersonal, and conventionally commercial. Malcolm’s stint in prison, the part of the movie that comes closest to Baldwin’s original script, is probably the most didactic stretch in both works, and in the movie it certainly carries some of Baldwin’s power (though paradoxically, the most potent and poetic part of this section — a meditation on the dictionary definitions of “black” and “white” — is not in Baldwin’s version).

Perhaps the most beautiful part of Baldwin’s script, its handling of colloquial black speech, is missing from much of both the Autobiography and the movie, perhaps for related reasons. As John Edgar Wideman points out in a fascinating essay on the Autobiography included in the collection Malcolm X: In Our Own Image, which focuses on Alex Haley’s scrupulous invisibility as a mediator of Malcolm’s voice and narrative, “Haley finesses potential problems by sticking to transparent, colorless dialect.” But if Haley’s colorless dialect and Baldwin’s funky dialect both conjure up living, breathing worlds, Lee’s jazzy stylistic flourishes in a void can at best only conjure up rhetorical attitudes — most of them middle-class responses to a working-class hero with a working-class audience.

I don’t mean to suggest, however, that Baldwin’s original script is flawless as a recounting of Malcolm’s life and death. Lee is right to criticize the “last act” of the Perl rewrite (a criticism which applies also to Baldwin’s original) for the absence of Elijah Muhammad as a character — still alive when these scripts were written — as well as its neglect of other factors relating to Malcolm’s eventual martyrdom, such as possible roles played by the FBI. (On the other hand, casting John Sayles as one of the FBI agents wiretapping Malcolm’s phone immediately trivializes this theme for the sake of some nudging film-buff gratification — another form of product placement.) Unfortunately, many of the obfuscations that Lee objects to are still central parts of the movie and have apparently been retained because a more truthful version would have led to embarrassing difficulties with Malcolm’s family.

For starters, it should be noted that it was Malcolm X’s own brothers and sisters in Detroit and Chicago who brought about his conversion to the Nation of Islam when he was in prison, which is made perfectly clear in the Autobiography. None of this is alluded to in Baldwin’s version, which invents a fellow prisoner and father figure — called Luther in the original script and Baines (Albert Hall) in the movie — and most reviewers and other publicists have been going along with this deception by calling this character a “composite.” (It’s true that Malcolm’s self-education in prison was inspired by a fellow inmate — an “old-time burglar” he calls “Bimbi,” who also tutored him in “some little cellblock swindles” — but it’s rather cavalier to assume that any character, much less this one, could represent a combination of “Bimbi” and Malcolm’s siblings — and Elijah Muhammad himself in the case of Luther — without some major distortions. And furthermore, the narrative functions performed by Luther/Baines’s son Sidney in the movie make the distortions even more elaborate.)

The fact that some of Malcolm’s siblings remained Muslims after their brother broke with Elijah Muhammad — and that, according to Marshall Frady’s recent article in the New Yorker, two of his brothers publicly denounced Malcolm as “a man who was no good” even after his death — raises questions that Lee obviously prefers to avoid. He similarly neglects to follow up on the claim made to him by Yusuf Shah, the former head of the Fruit of Islam, and reported in By Any Means Necessary that Malcolm had at different times shown interest in marrying two secretaries whom he much later discovered Elijah Muhammad had impregnated — a situation heavy with oedipal implications that increases one’s sense of familial betrayal.

Thanks to such strategic avoidances, a great deal of the movie’s energies seem to be devoted to marshaling offscreen sound bites to play over aerial shots of crowds (in keeping with the De Mille movies Lee emulates) rather than delving too deeply into Malcolm X’s psyche or personal life. And when it comes to making any ideological distinctions — such as dealing directly with the reactionary misogyny of certain Muslim teachings, highlighted in Malcolm’s intercut parallel dialogues with Betty Shabazz (Angela Bassett) and Elijah Muhammad (Al Freeman Jr.) and in a prominent banner at one of the rallies (“We Must Protect Our Most Valuable Property — Our Women”) — the movie can mainly only hem and haw and look the other way, waiting for Malcolm’s next press conference to come into view.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X may be the best book ever written about what it means to be black and American — even better than Richard Wright’s Native Son and Black Boy or James Baldwin’s early essays. For its mercurial intelligence, its value as social and cultural history, its stinging power as critique and indictment, its indelible character sketches, its moral and polemical rage, its dialectical sense of development, its meticulous self-scrutiny as seen through several overlapping identities and self-portraits, and its feeling for atmosphere and detail, it is clearly one of the most valuable of all 20th-century American autobiographies.

The cheapest paperback edition is $5.95 — a buck less than what it costs to see Malcolm X in Chicago, and $7 less than By Any Means Necessary. And the immediate pleasure of reading it will last more than twice the length of the movie.

The possibility that the movie will encourage some people to read the book has to be weighed against the fact that it will provide many others with a perfect excuse not to go anywhere near it, bolstered by the unshakable (if unjustifiable) confidence that, thanks to Spike Lee, they now know what the Autobiography consists of, sort of. And even though it costs us about a dollar more to purchase this pseudoknowledge than it does to expose ourselves to the genuine experience of the book itself, we all know which choice Entertainment Tonight has already made for us, well in advance.

I’m not claiming that The Autobiography of Malcolm X, great as it is, is any model of fact checking and truth telling. Sometimes myths and simplifications are necessary tools in political struggles. It makes more sense, for instance, to claim that the civil rights struggle started when a black woman spontaneously refused to relinquish her seat on a bus to a white man in Montgomery, Alabama, than to state that this action was planned well in advance — by Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr., among others — at a meeting held in Monteagle, Tennessee.

Similarly, as various scholars have shown, the Autobiography, which certainly had political purposes of its own, is guilty in spots of hyperbole and invention. There are documented reasons to at least question such matters, left unquestioned by Lee, as the nature and extent of Malcolm’s early criminal career, whether Malcolm’s father’s house was really burned by the Klan, and whether years later Malcolm’s own house was burned by the Muslims. (The movie is somewhat more open about the degree to which Malcolm may have been complicitous in his own assassination and martyrdom by deliberately avoiding certain security precautions.) Even so, the Autobiography is valuable as myth, and one can easily understand Lee’s desire to preserve that myth. On the other hand, the political agenda of this movie cannot by any stretch of the imagination be equated with that of the Autobiography, much less Baldwin’s original script. Let’s consider how each of them end. The Autobiography, not counting Ossie Davis’s eulogy, has two endings. The first comes from Malcolm: “If I can die having brought any light, having exposed any meaningful truth that will help to destroy the racist cancer that is malignant in the body of America — then, all of the credit is due to Allah. Only the mistakes have been mine.” The second comes from Alex Haley in his lengthy epilogue: “It still feels to me as if [Malcolm X] has gone into some next chapter, to be written by historians.”

The movie — again, not counting Ossie Davis’s eulogy, which is heard over archival footage of Malcolm (mixed in with a few matching black-and-white shots of Denzel Washington a la JFK) — also might be said to have two endings, though Lee originally wanted it to have only one: the following text by Malcolm X as recited by Nelson Mandela: “We declare our right on this earth to be a man, to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.” Mandela refused to speak the last phrase, so Lee cuts to Malcolm X himself saying it.

On the face of it, Lee’s ending might sound more radical than either Malcolm X’s or Haley’s. But if we consider that By Any Means Necessary is also the title of Lee’s book about his efforts to get his movie made, the implied equation between the rights of all black people to be considered human beings and the desire of privileged hotshot Lee to make a big-budget movie based on other corny period biopics can only be seen as a business move, not as an ethical or artistic statement worth repeating. To paraphrase Haley, it feels to me as if Malcolm X himself has gone into some next chapter, now written by Warner Communications. If Spike Lee, who signs this text, thinks that either he or Malcolm wrote it, he has rocks in his head; radical sound bites or not, most of the heart and guts of this movie was written by Hollywood studios years before he was born. But maybe you have to believe such nonsense if you want to get ahead.