Here are five more of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007). — J.R.

Scene

1957 / Paths of Glory – Timothy Carey kills a cockroach.

U.S. Director: Stanley Kubrick. Cast: Ralph Meeker, Timothy Carey.

Why It’s Key: A quintessential character actor achieves his apotheosis when his character kills a bug.

To cover up his vain blunders, a French general (George Macready) in World War I orders three of his soldiers (Ralph Meeker, Joe Turkel, Timothy Carey), chosen almost at random, to be court-martialed and then shot by a firing squad for dereliction of duty, as an example to their fellow soldiers. When their last meal is brought to them, they can mainly only talk desperately about futile plans for escape and the hopelessness of their plight. Then Corporal Paris (Meeker) looks down at a cockroach crawling across the table and says, “See that cockroach? Tomorrow morning, we’ll be dead and it’ll be alive. It’ll have more contact with my wife and child than I will. I’ll be nothing, and it’ll be alive.” Ferrol smashes the cockroach with his fist and says, almost dreamily, “Now you got the edge on him.”

We’re apt to laugh at the absurdism and grotesquerie of the moment — especially Timothy Carey’s deadpan delivery, as if he had a mouthful of mush and was soft-pedaling the phrase like Lester Young on his tenor sax. One of the creepiest character actors in movies, he doesn’t fit the period; even if we accept him as a French soldier, accepting him as one in World War I is more of a stretch, because he registers like a contemporary beatnik. That’s also how he comes across in East of Eden, One-Eyed Jacks, The Killing, or The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. But for precisely that reason, he gives the line the existential ring it deserves.

Scene

2006 / Offside — The singing of the Iranian national anthem at the end.

Iran. Director: Jafar Panahi.

Why It’s Key: Panahi shows how he can be a populist without compromising his politics.

It’s near the end of this raucous and pointed Iranian comedy, and a bunch of young girls, who disguised themselves as boys in order to sneak into a soccer match in Tehran where girls are strictly forbidden, have been caught and arrested by reluctant cops and taken off in a kind of paddy wagon. Then the news suddenly breaks that the home team has won, meaning that Iran qualifies for the World Cup, and girls and cops alike are so overcome with joy that the girls are temporarily set free, celebratory sparklers and sweets are passed around, and the strains of the national anthem are heard on the soundtrack.

What does one make of this final detail? Up until now, this deft fusion of laughter and suspense, documentary and fiction, has functioned a bit like a comic and highly commercial remake of Panahi’s earlier (and banned) The Circle (2000) — a much artier work of protest against the oppression of women in Iran. Could the anthem be viewed as some sort of concession to the mullahs, who wound up banning this movie anyway — even though it may conceivably have helped inspire the President, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, to try to revise the law and admit girls into sporting events, at least until the mullahs overruled him? Not at all. Because the version of the national anthem being sung here is an older, pre-Revolutionary one, deliberately stirring the sort of nationalistic feelings that the mullahs have been suppressing in favor of promoting pan-Islamic identity.

Scene

1960 / Paris Belongs to Us – The screening of Metropolis.

France. Director: Jacques Rivette. Cast: Betty Schneider, François Maistre.

Why It’s Key: It’s the first film quotation in a New Wave feature, and far from gratuitous.

Exactly two hours into Jacques Rivette’s ambitious, 141-minute first feature, a complex and paranoid intrigue about Paris bohemians, we suddenly, and without warning, see the great “Tower of Babel” sequence from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. As this visionary sequence concludes, with the hands of rebels reaching up towards Heaven, the film breaks, exposing a blank white screen. We find ourselves in a living room, where Rivette’s heroine Anne (Betty Schneider), her brother Pierre (François Maistre), and many others have been watching the film.

It’s a perfect symbolic representation of the tormented Parisian world Anne has encountered over the course of the plot — populated by a struggling theater group rehearsing Pericles and such exiles as a recently suicided Spanish composer and a victim of American McCarthyism, and characterized by intimations of a real or imagined worldwide conspiracy that Anne has stumbled upon. In short, it’s a chaotic Tower of Babel that hovers over a frightening void. And just as the jumble of languages produces incoherence, the mix of all colors produces white, yielding a blank screen.

The epigraph of Rivette’s haunting feature is “Paris belongs to no one,” and just as Betty’s perception shifts back and forth between a surfeit and an absence of information, and Paris figures as either a comforting possession or a threat, Rivette’s metaphysics alternates between a paranoid universe where everything signifies and an absurdist universe where nothing has meaning. In this film by a film critic, Metropolis’s Babel becomes the clinching cross-reference that clarifies the starkness of Rivette’s design.

Scene

1959 / The Indian Tomb – Debra Paget dances with a fake cobra.

West Germany/France/Italy. Director: Fritz Lang. Cast:

Debra Paget. Original title: Das indische Grabmal.

Why It’s Key: Unabashed erotic kitsch from a visionary filmmaker.

There are two erotic temple dances performed inside a cave by Seetha (Debra Paget) — the betrothed of the Maharajah of Eschnapur, the hero’s employer — in Fritz Lang’s two-part 1959 remake of an exotic fantasy he coscripted with Thea von Harbou back in 1920. Thirty-odd minutes into The Tiger of Eschnapur, she performs at the foot of a huge statue of a goddess, briefly writhing within the palm of her outstretched hand. And forty-odd minutes into The Indian Tomb, long after Seetha has fallen into a romantic relationship with the hero, she has to prove her innocence to the temple priests by dancing with a cobra. The cobra rise and then lunges to strike her, but the Maharajah kills it first, offending the priests by violating their sacred rites.

This has all the earmarks of high camp because the cobra, clearly a tawdry prop, is being pulled around with wires, and Paget is wearing a silver-colored bikini that’s fit for a Las Vegas showgirl. But for all its kitschiness, this scene isn’t camp at all because Lang believes in what he’s showing on some level, and gives the scene the hypnotic intensity of a private obsession. In Seetha’s first dance, both the Maharajah and the hero (more briefly) figure as the voyeurs of her performance, but the second time, even though the Maharajah is present, Lang’s mise en scene implies that the only voyeurs who matter are neither the Maharajah nor the priests, just Lang and us — the only gods who really matter.

Scene

1928 / Spione – The hero’s bath is prepared.

Germany. Director: Fritz Lang. Cast: Paul Hörbiger.

Why It’s Key: A calm oasis of peace and luxury in the midst of a tight, sinister thriller.

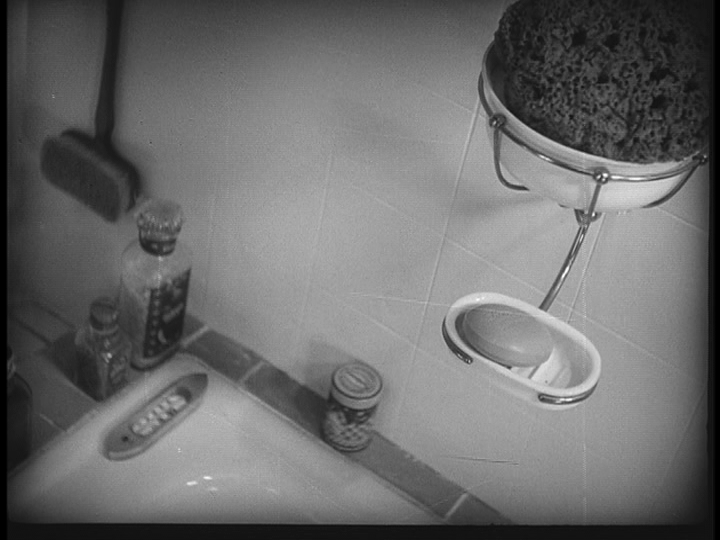

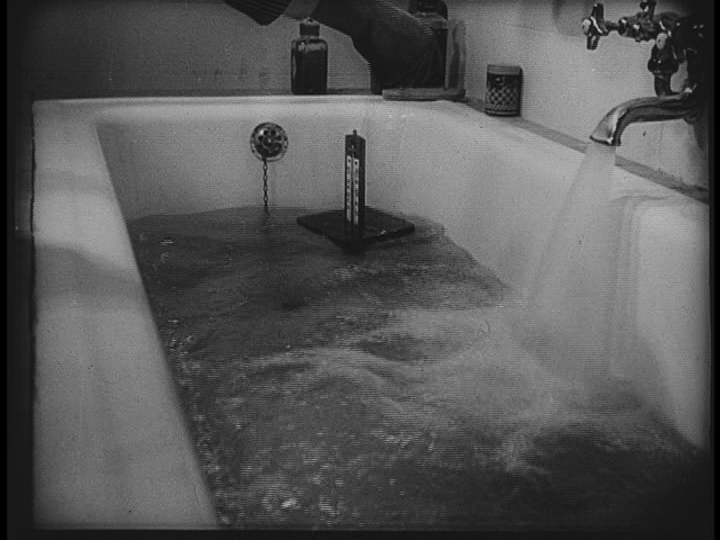

It’s a brief montage of four shots, sandwiched in the middle of a sequence packed with action and intrigue, offering us an elliptical breather in the midst of Lang’s most suspenseful thriller. Two hands emerge from the foreground in close-up to turn on a bathtub’s spigots; a hand places a fresh bar of soap in the soap dish; a fresh towel is draped over the towel rack; and a fancy thermometer is dipped in the tub’s water by the same hand, pulled out so the temperature can be checked, then set afloat while bath salts are sprinkled in the water.

From the sleeve of a striped jacket, we know the hands belong to the hero’s valet (Paul Höbiger), dutifully preparing his master’s bath. Just before, the hero (Willy Fritsh) — a detective identified in the credits as “No. 326,” disguised as a filthy tramp — has returned to his hotel suite via roof and fire escape, only to be greeted by a sexy spy (Greda Maurus) who’s just shot a man in the next room whom she claims was attacking her and run to 326’s room for refuge. In fact, this is a seductive ruse; she’s been sent by the villain to 326’s room to find information about a secret treaty, and just after the bath montage, we see her find and steal a document from his desk while he’s still bathing and dressing. So the hero’s bath is never shown or depicted, yet Lang evokes it vividly and even luxuriously through the elaborate way his servant prepares it.