From The Village Voice (May 13, 2008). — J.R.

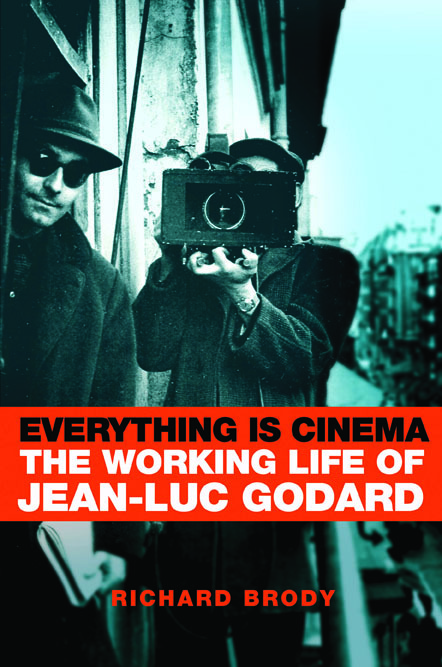

Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard

By Richard Brody

Metropolitan Books, 701 pp., $40

Will we ever get a critical biography of Welles, Kubrick, or Eastwood as good as Brian Boyd’s two volumes on Vladimir Nabokov? Probably not. Novelists basically have friends, relatives, and editors to be interviewed, but with high-profile movie directors, one also has to contend with countless employees, potential as well as actual. And the complications introduced by showbiz gossip about mythical and controversial figures are endless: While these stories make for compulsive reading, they interfere with criticism and scholarship.

With all that extra and unwieldy baggage in tow, a biographer may find it impossible to create a critical through-line that’s both persuasive and comprehensive. Even in the best books of this kind, either the life overrides the films (as in Joseph McBride’s Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success) or the criticism trumps the biography (as in Chris Fujiwara’s Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall). And taking on a maven as prolific, innovative, and constantly changing as Jean-Luc Godard, biographer Richard Brody is clearly asking for trouble.

Perhaps the most impressive thing about Brody’s Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard is that it’s 700 large-format pages long, yet winds up seeming too short — a tribute to both the author and his 77-year-old subject. Read more

From the Summer 2004 issue of Cineaste. — J.R.

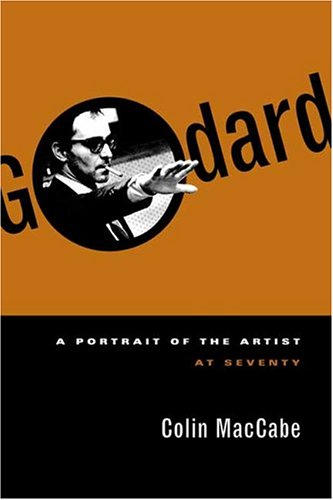

Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy

by Colin MacCabe. Filmography and picture research by Sally Shafto. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003. 432 pp, illus. Hardcover: $25.00.

This isn’t an authorized biography of Jean-Luc Godard. But it appears to have qualified briefly as a book that might have become one after Colin MacCabe first embarked on it in the mid-Eighties. “Two years later,” he reports in his Preface, “he” — meaning Godard — “asked me how the work was progressing and this encouraged me to bury my own doubts and to prepare a very detailed treatment. By the early nineties, however, it was clear that Godard no longer had any faith in the project.”

MacCabe says nothing to explain this change of heart and loss of faith. A look, however, at one version of his detailed treatment — “Jean-Luc Godard: A Life in Seven Episodes (to Date),” published in Raymond Bellour’s 1992 Museum of Modern Art collection Jean-Luc Godard Son + Image, 1974-1991 — provides a plausible reason, especially if one zeroes in on the following passage in the second episode: “The South American journey came to an end [in Rio] when Godard’s father once again refused to support his son any longer. Read more

From the August 2, 1991 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

The last film of F.W. Murnau, who was probably the greatest of all silent directors (he didn’t live long enough to make sound films, as he died in an auto accident only a few days after work on the musical score of this masterpiece was completed). Filmed entirely in the South Seas with a nonprofessional cast and gorgeous cinematography by Floyd Crosby (fully evident in this fine restoration), this began as a collaboration with the great documentarist Robert Flaherty, who still shares credit for the story, though clearly the German romanticism of Murnau (Nosferatu, The Last Laugh, Sunrise) predominates, above all in the heroic poses of the islanders and the fateful diagonals in the compositions. The simple plot is an erotic love story complicated by the fact that the young woman becomes sexually taboo when she is selected by an elder (one of Murnau’s most chilling harbingers of doom) to replace a sacred maiden who has just died. The two “chapters” of the film are titled “Paradise” and “Paradise Lost,” and another theme is the corrupting power of “civilization” — money in particular — on the innocent hedonism of the islanders. Read more