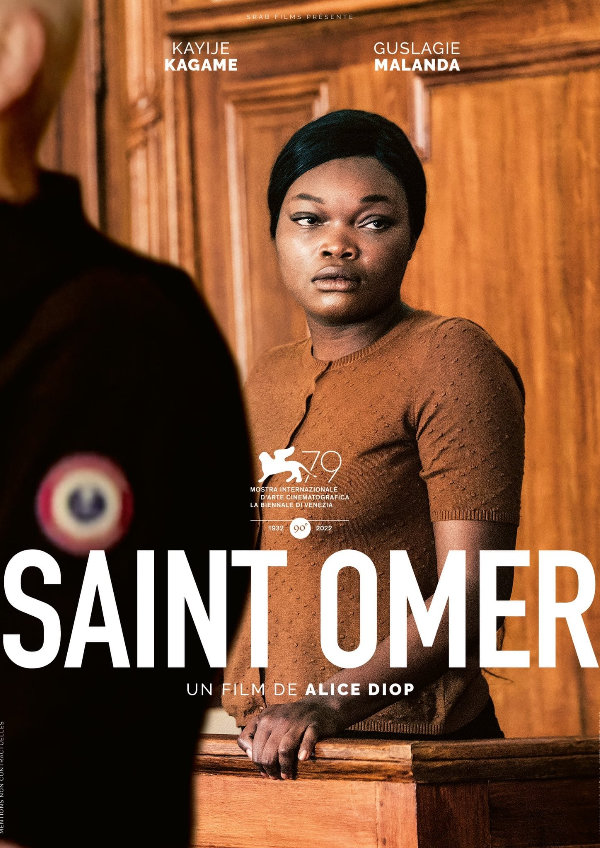

Like almost every other year within recent memory, I wind up seeing a masterpiece after I can vote for it or include it in any poll. Alice Diop’s first fiction feature is a classical example of a film that asks questions more than provides answers, and one of its best ways of posing or suggesting questions is not cutting to a reverse angle whenever you’re expecting it to. This is a film carried largely by its close-ups and its dialogue, and many of its reverse angles are between its two protagonists, two young and black Senegalese women in France who never meet, although they do exchange glances at one climactic, privileged moment. It’s a film devoted to a trial whose outcome is never recorded, but it has generated enough questions by the end to make a verdict seem either impossible or superfluous. Consciously or not, it carries more than one echo of Ousmane Sembene’s great La noire de… (Black Girl, 1966). [1/3/2023]

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1992). — J.R.

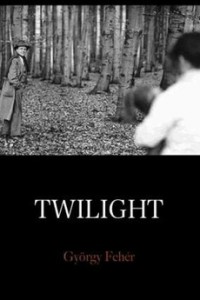

A dirgelike Hungarian thriller by Gyorgy Feher about the search for a serial killer whose victims are little girls. The striking visual style (high-contrast black-and-white cinematography by Miklos Gurban) and creepy pacing tend to dominate the plot so thoroughly that I found myself tuning the narrative out and not being terribly worried about what I was missing. While the slow-as-molasses dialogue delivery and camera movements superficially suggest Tarkovsky (or, closer to home, Bela Tarr’s Damnation), Feher’s script and mise en scene are considerably more mannerist — employed more to conjure an atmosphere than to convey a particular vision or a distinctive moral universe. The closest American equivalent to this sort of exercise might be Rumble Fish: sumptuous visuals that impart more filigree than substance (1990). (JR)

Read more

Read more

Written for the Vancouver International Film Festival, and published September 30, 2006. — J.R.

Read more

Read more