From Paris Journal, Film Comment, Summer 1972 (excerpt). –J.R.

Nearly two decades have elapsed between the making of Samuel Fuller’s PARK ROW and its premiere at the Cinema Mac-Mahon. In the interim, Fuller has gone from being a cause célèbre in France to a critical industry in England, where no less than three books on his films have already appeared. A major limitation of this overkill, which is threatening to “assimilate” Douglas Sirk as its next victim, is its absolute humorlessness — a quality that was rarely present in Godard’s or Luc Moullet’s writing on either director in the 50s. Reviewing Sirk’s A TIME TO LOVE AND A TIME TO DIE, Godard affirmed that “ you have to talk about this kind of thing…deliriously, you can be quietly, or passionately delirious, but delirious you have to be, for the logic of delirium is the only logic that Sirk has ever bothered about.” In addition to being about as delirious as the London Times, most of the English writing about Sirk and Fuller suffers from myopia as well. Compare Moullet’s three half-pages on Sirk’s THE TARNISHED ANGELS (Cahiers du cinéma #87) to Fred Camper’s 25 pages in the recent Sirk issue of Screen: the former, for all its giddiness, develops a persuasive stylistic link between Faulkner’s rhetoric and Sirk’s mobile camera; the latter, for all its sobriety, fails to mention the words “Faulkner” or “Pylon” even once. Read more

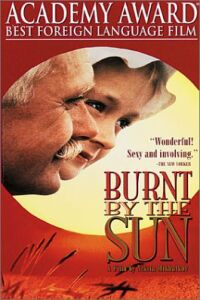

From the May 1, 1995 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Trying to figure out why this interminable, hammy piece of Russian nostalgia by Nikita Mikhalkov (director, cowriter, associate producer, and star) won the Oscar for best foreign film of 1994 and the grand jury prize at Cannes, I came up with four hypotheses: (1) there are no Asians in it; (2) set over one long summer day in the country in 1936, it provides a wake-up call about the dangerously underhanded doings of Joseph Stalin; (3) the hero appears to be well over 60; and (4) the elegiac Chekhovian style recalls Ingmar Bergman by way of Woody Allen, thus making the film seem trebly familiar. Indeed, apart from intermittent bursts of Edouard Artemiev’s bombastic music, this 134-minute period piece offers the ideal opportunity for a long, peaceful snooze. With Oleg Menchikov, Ingeborga Dapkounaite, and Nadia Mikhalkov. In Russian with subtitles. (JR)

Read more

Written for the December 2022 issue of Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. — J.R.

I’ve recently been working on a book that collects my uncollected film, literary, and jazz criticism, ordering all my inclusions chronologically so that they’re allowed to commingle, meanwhile exploring ways that all three of these art forms (film, literature, music) can inform and reflect one another. Because this project rejects the “targeting” mentality ruling academic presses and their all-powerful publicists—which follows the Reaganite economic principle of exploiting and exhausting markets that already exist, not proposing new ones—it took me some time to find a publisher.

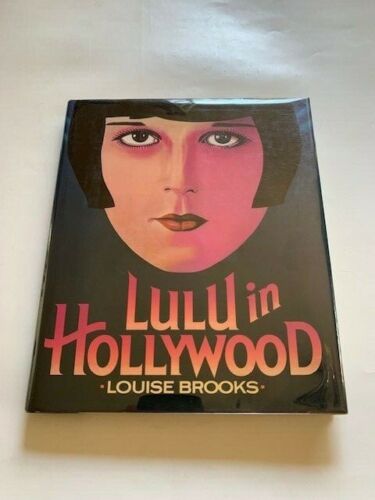

Still more recently, I’ve been rereading Louise Brooks’ informative, thoughtful, and beautifully written Lulu in Hollywood, a collection of essays combining autobiography with criticism, film history with social and fashion history, and even a certain kind of fiction with non-fiction.

The latter combination requires some explanation. While recounting her memories of her own acting in films (especially Beggars of Life and Pandora’s Box) and of Humphrey Bogart, Charlie Chaplin, W.C. Fields, Greta Garbo, Lillian Gish, the neglected director Edmund Goulding, and the even lesser known Pepi Lederer (lesbian niece of Marion Davies, older sister of screenwriter Charles Lederer, and close friend of Brooks who committed suicide at the age of 25), Brooks renders scenes in such fulsome and intricate detail—extended dialogue, facial expressions and gestures, locations, furnishings, clothes, food and drink at meals—that it quickly becomes apparent that she must be fleshing out whatever she can remember with imagined specifics. Read more

Participant:

Jonathan Rosenbaum, critic (joinathanrosenbaum.net) and sometime educator (FilmFactory, KinoKlub in Split), United States

Films:

1.

The Banshees of Inisherin, Martin McDonagh, 2022

Memoria, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2021

Men, Alex Garland, 2022

Potemkinistii, Radu Jude, 2022

Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, 2021

I have conflicted relations to all five – even Memoria, the only one I’ve seen twice and which I’m still trying to understand. The Jude film is a short, and the Hamaguchi feature beautifully juxtaposes three formally and thematically related shorts.

The Banshees is the first McDonagh film I’ve halfway liked–much as Tár, its big-city near-equivalent in social critique, is the first Todd Field film I’ve halfway liked. But the facile defeatism of both features depresses me: small-town stupidity and brutality motored by a colossal sense of entitlement, big-city smarts comparably preening and braying through the brutality of celebrity culture. Both register like bad jokes told with enough sarcastic relish and wit to make them sporadically blossom out of their gnarled bitterness into something resembling good jokes

`

2.

American: An Odyssey to 1947, Danny Wu, 2022. This documentary about Orson Welles’ politics in the 30s and 40s doesn’t even have a distributor yet, but it taught me a lot. Read more