Brother Carl

From the Chicago Reader (November 1, 1992). Too bad that this hasn’t been made widely available either online or on disc–although I’ve just discovered that a Swedish DVD exists (see below). I much prefer it to Sontag’s previous feature, Duet for Cannibals, which recently came out in both formats. — J.R.

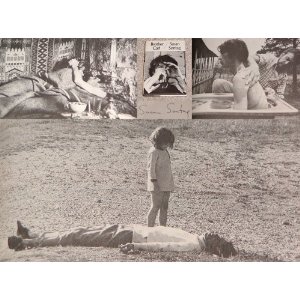

Susan Sontag’s seldom-seen second feature — filmed in Sweden like her first (Duet for Cannibals) but in English and with a cast of Swedish and French actors — shows the influence of Bergman’s Persona, Dreyer’s Ordet, and Whale’s Frankenstein as it depicts two tortured relationships, a suicide, and a miracle. The major characters include an unhappily married couple, a mainly mute former dancer (Laurent Terzieff) who occasionally suggests Nijinsky, and an autistic child. The results can’t exactly be called the work of a natural filmmaker, but they’re fascinating for anyone interested in following the themes and formal concerns of Sontag’s fiction as well as some of her essays, including “On Silence”. This is no masterpiece, but it certainly deserves more attention than it’s received (1971). (JR)