From the Chicago Reader (December 7, 1990). — J.R.

MISERY

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Rob Reiner

Written by William Goldman

With James Caan, Kathy Bates, Richard Farnsworth, Frances Sternhagen, and Lauren Bacall.

Although it didn’t impress me too much when I first saw it, The King of Comedy has gradually come to seem the most important and resonant of Martin Scorsese’s features, largely because of all it has to say about the values we place on both stars and fans in contemporary society. Part of what makes it so pungent is the casting: by all rights, talk-show star Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis) should be the “hero” and his crazed kidnapper-fans Rupert and Masha (Robert De Niro and Sandra Bernhard) the “villains”; but De Niro after all is a charismatic star in his own right, while Lewis has long been someone Americans love to hate. The same kind of twist on stereotypes occurs in the story: Rupert is an obnoxious loser and Masha a borderline psycho, but Langford’s offstage persona is so morose and unpleasant that next to him they seem like models of humanity. To make matters even more disturbing, Masha clearly regards Langford as a substitute for her own neglectful parents, and Rupert’s climactic stand-up comedy debut, won as a ransom for kidnapping Langford, largely consists of contemptuously trashing his own family and background. Read more

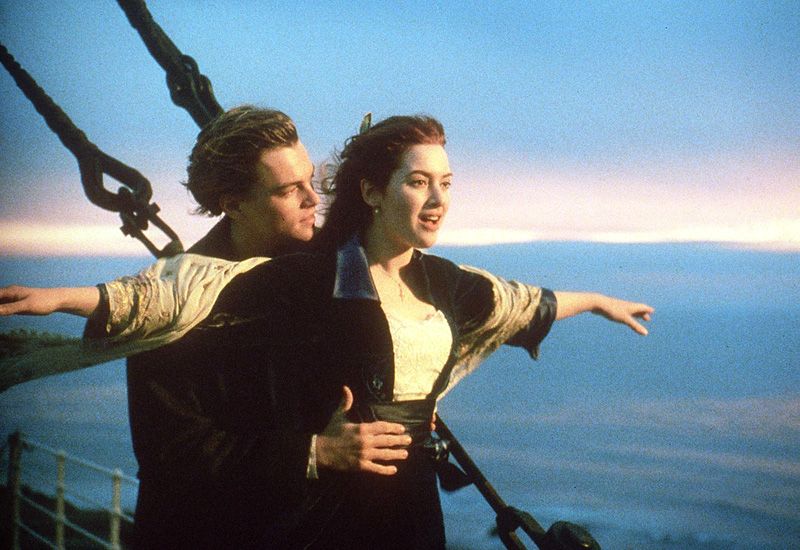

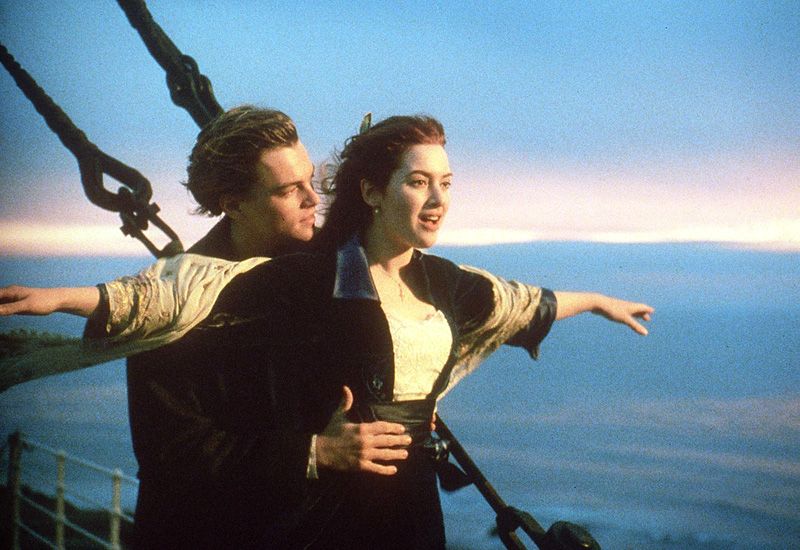

From the Chicago Reader (December 19, 1997). — J.R.

Titanic

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by James Cameron

With Leonardo DiCaprio, Kate Winslet, Billy Zane, Kathy Bates, Frances Fisher, Gloria Stuart, Bill Paxton, Bernard Hill, and Suzy Amis.

I suppose there’s something faintly ridiculous about a $200-million movie that argues on behalf of true love over wealth and even bandies about a precious diamond as a central narrative device — like Citizen Kane’s Rosebud — to clinch its point. Yet for all the hokeyness, Titanic kept me absorbed all 194 minutes both times I saw it. It’s nervy as well as limited for writer-director-coproducer James Cameron to reduce a historical event of this weight to a single invented love story, however touching, and then to invest that love story with plot details that range from unlikely to downright stupid. But one clear advantage of paring away the subplots that clog up disaster movies is that it allows one to achieve a certain elemental purity.

This movie tells you a great deal about first class on the ship, a little bit about third class, and nothing at all about second class. According to Walter Lord’s 1955 nonfiction book about the sinking of the Titanic, A Night to Remember, which includes a full passenger list, 279 of the 2,223 passengers were in second class, and 112 of them survived. Read more

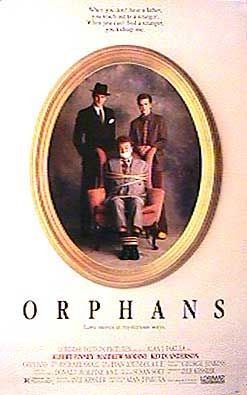

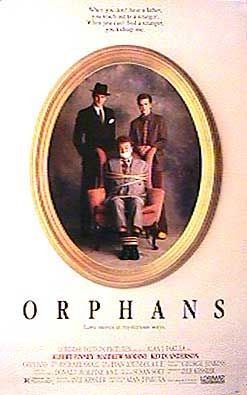

From the Chicago Reader, September 25, 1987. — J.R.

ORPHANS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Alan J. Pakula

Written by Lyle Kessler

With Albert Finney, Matthew Modine, Kevin Anderson, and John Kellogg.

Although the conventional Hollywood wisdom about adapting plays into movies is that plays should be “opened up,” the practical effect of this is often roughly equivalent to letting the air out of tires: the air may circulate more freely, but the wheels no longer turn. Fortunately Alan J. Pakula is a sensible enough man to recognize this danger, and the best thing that can be said about his movie of Orphans is that, by and large, he has allowed the original play to remain a play. Indeed, only by respecting the integrity of the original has he managed to adapt it into a fairly successful movie.

A contemporary play set in the present, Lyle Kessler’s Orphans has a distinctly uncontemporary, even old-fashioned flavor to it. Largely concerned with intense family relationships and feelings — between brothers, and between father and sons — it has virtually no traces of sadomasochism, which alone suffices to make it unfashionable as theater in this post-Pinter era. In a time when Sam Shepard’s laconic Marlboro ads are experienced as existentially authentic, and Wallace Shawn’s intricate lacerations and varieties of self-loathing are regarded as cathartic, Kessler’s primal depictions of brotherhood and fatherhood, without the usual smirking ironies, are simple and direct to the point of embarrassment. Read more

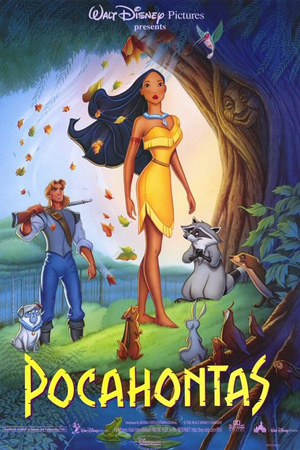

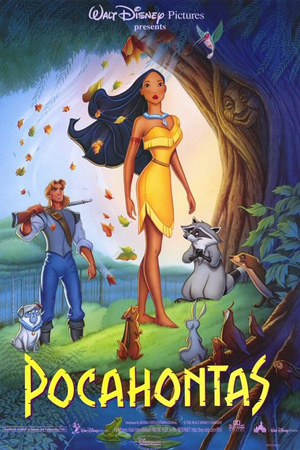

From the Chicago Reader (June 30, 1995). — J.R.

Pocahontas

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Mike Gabriel and Eric Goldberg

Written by Carl Binder, Susannah Grant, and Pillip LaZebnick

With the voices of Irene Bedard, Judy Kuhn, Mel Gibson, David Ogden Stiers, Linda Hunt, Russel Means, Christian Bale, Billy Connolly, and Joe Baker.

American history without Smith and Pocahontas is hard to imagine. If the void were there, something else — yet something similar — would have to fill it. — Bradford Smith, Captain John Smith: His Life & Legend

I assume we’re still some years away from the abolition of state-supported schools and the gleeful handing over of our entire system of education to the Disney people. But some of the studio’s clever promotions for Pocahontas might make you conclude that some such changes have already taken place.

Consider the “special collector’s issue” of the kids’ magazine Disney Adventures devoted to “Pocahontas: The Movie, The Stars, The Real-Life Story,” complete with ads for some of the spin-off products. It afforded me almost as much food for thought as the two hours I spent in a library reading through historical accounts of what “really” happened in the wilds of Virginia in the early 17th century. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 28, 2006). — J.R.

Scoop

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Woody Allen

With Scarlett Johansson, Allen, Ian McShane, Hugh Jackman, Fenella Woolgar, and Julian Glover

Unlike some of his more commercial contemporaries — including Harvey Weinstein pets Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino — Woody Allen has always had the final cut on his movies. But then what are the corporate honchos risking with this indulgence? They know familiarity is one of many things that draw us to movies, and they know with Allen not to expect any surprises. Unfortunately the industry often behaves as if familiarity were the only attraction.

Match Point, Allen’s best movie to date, was criticized in some quarters because it transplanted many of his concerns from New York to London and because it had an uncharacteristic seriousness and precision. Scoop, its lame successor, is also set in London and also costars Scarlett Johansson as another American greenhorn (a journalism student instead of an aspiring actress) who becomes involved with another wealthy Englishman who has a country estate. And once again there’s the plotting of the murder of a girlfriend that calls to mind Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy. Read more

From Filmmaker, Fall 1993 (vol. 2, #1). – J.R.

One reason why quieter, less obviously trendy North American festivals like those in Denver, Honolulu, and Vancouver attract me more as a critic than the hit-making events held in Sundance and Telluride is that they offer a genuine alternative to the feeding frenzies that accompany most current movie launchings — an atmosphere conducive to looking at movies without the usual starstruck distractions . By the same token, one advantage of Locarno over bigger and better publicized competitive European festivals like Cannes, Berlin and Venice is that it takes place in a more relaxed ambience, a space to think in.

Held in a lakeside resort town in the Italian speaking part of Switzerland in early August, where nightly outdoor screenings in the Grand Piazza for up to 7,000 spectators are the main public events, the festival also boasts exhaustive retrospectives, a Critics Week devoted to documentaries, an annual assortment of films about film, and many other sidebars and special events. One of the many specialty items this year was a series of clever, elaborate commercials for Bris Soap made by Ingmar Bergman in the early 50s. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 1989). — J.R.

CASUALTIES OF WAR

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Brian De Palma

Written by David Rabe

With Michael J. Fox, Sean Penn, Don Harvey, John C. Reilly, John Leguizamo, Thuy Thu Le, and Erik King.

“It is, of course, immediately evident that there is a possible position omitted from the fierce debate between the hawks and the doves, which allegedly tore the country apart during these trying years: namely, the position of the peace movement, a position in fact shared by the large majority [over 70 percent] of citizens as recently as 1982: the war was not merely a ‘mistake,’ as the official doves allege, but was ‘fundamentally wrong and immoral.’ To put it plainly: war crimes, including the crime of launching aggressive war, are wrong, even if they succeed in their ‘noble’ aims. This position does not enter the debate, even to be refuted; it is unthinkable, within the ideological mainstream.” — Noam Chomsky, “The Manufacture of Consent” (1984)

I’ve never been much of a Brian De Palma fan, but it would be silly to deny that Casualties of War shows his talents, such as they are, at their near best — disregarding for the moment what he does with them. Read more

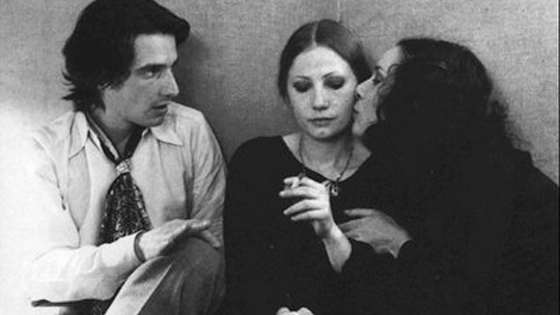

From the Chicago Reader (January 22, 1999). For my earlier take on this film, written when it was released in London, go here. — J.R.

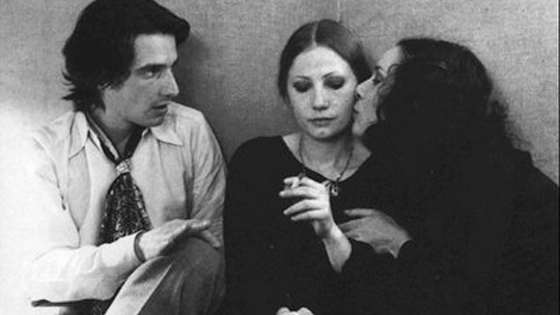

The Mother and the Whore

Rating **** Masterpiece

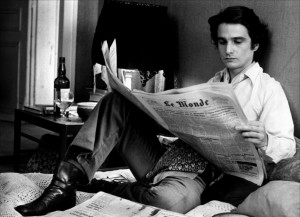

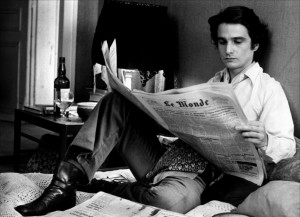

Directed and written by Jean Eustache

With Jean-Pierre Leaud, Francoise Lebrun, Bernadette Lafont, Isabelle Weingarten, Jacques Renard, Jean Douchet, and Jean-Noel Picq.

I have a friend who had a wonderful idea: he wanted to have his right hand amputated. Very seriously. Went to see a surgeon, said, ‘How much does it cost, I’m ready to pay.’ He wanted to have a porcelain hand made to replace it. And in his home, in a room, in the very center of the room, to place his real hand in formaldehyde, with a plaque reading, ‘My hand, 1940-1972’. And people would come to visit, like they’d go to an exhibit.

— Alexandre in The Mother and the Whore

Is it permissible to disapprove of a masterpiece? I find Jean Eustache’s obsessive, 215-minute black-and- white The Mother and the Whore, playing nine times this week at Facets Multimedia Center, every bit as mesmerizing today as I did when I attended the premiere at Cannes in 1973. I must have seen it four or five times since, the last time in the early 80s. Read more

My column for Caimán Cuadernos de Cine, submitted in late April for their June 2020 issue. Happily, both Her Socialist Smile and A House is Not a Home: Wright or Wrong are both readily available now via streaming.– J.R.

I suppose one could say that the coronavirus has been “good” for my web site because more people visit it now. In much the same fashion, and with an equivalent amount of innocent perversity, Donald Trump is said to be “bad” for the United States (that is, most of the people in the United States) yet “good” for television —meaning the handful of billionaires who own and control television, all of whom are felt to be distinct from the United States.

What does it mean, really, to call anything in the media (television, radio, cinema, the Internet, my web site, your web site ) “good” without matching the interests of the people who go there or live there? Like the American delusion that only three kinds of people exist in the world — Americans, anti-Americans, and prospective Americans — this means excluding most of humanity from the playing field.

I once heard that when Jonas Mekas in 1970 received the news that Nasser had just died, his first thought was to ponder whether this was “good or bad for cinema”. Read more

Fourteen years ago, the underrated (or at least undervalued) Michael Kinsley reported in The New Yorker (“The Intellectual Free Lunch,” February 6, 1995, reprinted in his collection Big Babies) on a reputable survey that found that “75 percent of Americans believe that the United States spends ‘too much’ on foreign aid, and 64 percent want foreign-aid spending cut.” (“Apparently,” Kinsley added as an aside, “a cavalier 11 percent of Americans think it’s fine to spend ‘too much’ on foreign aid.”)

The same people were asked how much of the federal budget went to foreign aid, and “The median answer was 15 percent; the average answer was 18 percent.” But “the correct answer is less than 1 percent: the United States government spends about $14 billion a year on foreign aid (including military assistance) out of a total budget of $1.5 trillion.” When asked about how much foreign-aid spending would be “appropriate,” the median answer was 5 percent of the budget; and the median answer to how much would be “too little” was 3 percent, i.e. over three times the actual amount spent.

Kinsley then adds, “This poll is less interesting for what is shows about foreign aid than for what it shows about American democracy. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 7, 1998). — J.R.

Buffalo ’66

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Vincent Gallo

Written by Gallo and Alison Bagnall

With Gallo, Christina Ricci, Anjelica Huston, Ben Gazzara, Kevin Corrigan, Mickey Rourke, Roseanna Arquette, and Jan-Michael Vincent.

Vincent Gallo has proved himself a good actor in many films — in Arizona Dream, The Funeral, and several Claire Denis movies. But the first feature in which he functions as director, cowriter, composer, and star is a pathological curiosity. Candidly and painfully personal, Buffalo ’66 seems to spring from the kind of fantasies that inform movies almost exclusively — though vanity publishers offer similar opportunities. For me the film creates more embarrassment than sympathy, but at least it’s a kind of embarrassment that’s instructive. Its genre — narcissistic self-hatred reconfigured as a sense of entitlement — is far from exclusive to American movies, though it’s especially common in American independent efforts. Part of the self-hatred comes from the sense that it’s a disgrace to be poor, a sense more common in this country than in most other places, and poverty gives the film a distinctive musty odor — an ambience evident in such settings as a bowling alley and a cheap motel room. Read more

Sergei Eisenstein’s controversial, unfinished trilogy, with a Prokofiev score and a histrionic, campy (albeit compositionally very controlled) performance in the title role by Nikolai Cherkassov (1945). The ceremonial high style of the proceedings has been interpreted by critics as everything from the ultimate denial of a cinema based on montage (under Stalinist pressure) to the greatest Flash Gordon serial ever made. Thematically fascinating both as submerged autobiography and as a daring portrait of Stalin’s paranoia, quite apart from its interest as the historical pageant it professes to be, this is one of the most distinctive great films in the history of cinema — freakishly mannerist, yet so vivid in its obsessions and expressionist angularity that it virtually invents its own genre. 184 min. In Russian with subtitles. (JR)

Read more

Read more

This is the uncut version of a book review written for Stop Smiling no. 27 in 2006 (“Ode to the Midwest”), which had to be cut at the last minute due to space problems. My thanks to editor James Hughes for granting me permission to print the fuller version here. –J.R.

ICONS OF GRIEF: VAL LEWTON’S HOME FRONT PICTURES by Alexander Nemerov. Berkeley: University of Calornia Press, 2005. 213 pp.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Most film criticism has been hampered by the habit of dealing with narrative movies strictly and exclusively in terms of their stories. What’s overlooked by this practice is the fact that virtually all films are made up of nonnarrative as well as narrative elements—what might be described as both persistence and fluctuation, or nonlinearity as well as linearity. Even though we often prefer to think we experience movies only as unfolding narratives—which is apparently why what most people mean by “spoilers” always relate to plot and not to formal moves—how we remember these movies is part of that experience, and this partially consists of static images.

Consequently, it could be argued that we need more art historians writing about movies and fewer literary critics who operate from the model of narrative fiction. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 4, 2005). — J.R.

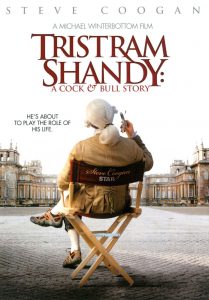

Laurence Sterne’s 18th-century masterpiece The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman is still the best of all avant-garde novels, and most of the fun of watching this screen version is wondering how writer Martin Hardy and director Michael Winterbottom will adapt what’s plainly unadaptable. They manage to anticipate almost every possible objection (even finding a cinematic equivalent for Sterne’s purposely blank page). This farce eventually runs out of steam, devolving into a protracted docudrama about actor Steve Coogan (who plays the title hero as well as his father), but until then this is a pretty clever piece of jive. With Rob Brydon (as Toby), Dylan Moran (as Dr. Slop), Keeley Hawes, and Shirley Henderson. R, 94 min. Century 12 and CineArts 6, Pipers Alley.

Read more

Read more

From the July 1, 2005 Chicago Reader.To celebrate a lovely new restoration coming out. — J.R.

Bert Stern’s film of the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival (1960; his only film) features Thelonious Monk, Louis Armstrong, Eric Dolphy, Chuck Berry, Dinah Washington, Mahalia Jackson, Anita O’Day, Gerry Mulligan, Chico Hamilton, and many others. Shot in gorgeous color, it’s probably the best feature-length jazz concert movie ever made. Despite some distracting cutaways to boats in the opening sections, it eventually buckles down to an intense concentration on the music and the audience’s rapport with it as afternoon turns into evening. Jackson’s rendition of “The Lord’s Prayer” is a particularly luminous highlight. Stern doesn’t seem to know what distinguishes mediocre from good or great jazz — he didn’t even bother to film Miles Davis at the same festival, and he allows a stupid announcement about boats to cover up part of a Monk solo — so all three get equal amounts of his attention. But he’s very good at showing people listening. 85 min. Gene Siskel Film Center. Read more