Here is my first-person reportage of the last laps of the original event, hurriedly written for the April 2, 1965 issue of the Bard Observer. I’ve only done a little bit of light editing on this text. — J.R.

Notes on the March to Montgomery

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

(Note: because of the haste with which this article was written, and because of its close proximity in time to the event itself, I cannot claim to be attempting anything definitive here, either in terms of impression or opinion. The following reactions are immediate and fragmented ones written only a few days after the march, and as such must suffer the defects of hurried writing and tentative suppositions. –- J.R.)

I

We arrived in Montgomery by Wednesday afternoon, following Highway 80 through the middle of town and heading towards St. Jude. a Catholic hospital complex on the city’s outskirts whose property was being used as a campsite for the marchers. We drove a rented Avis car; the Hertz people in Atlanta, when they overheard what we were up to, had told us that they had no cars available, but being hospitable Southern folk had driven us over to their competitors a few blocks away. The rain which had persisted for most of the day was beginning to slack off, and we were looking forward to the prospect of marching in good weather.

This would be the second time that I would march in Montgomery. The first time had been seven or eight years ago, when I was attending an Alabama high school and as a member of the band had been required to participate in the inauguration of Governor Patterson. I remember the city as being dirty and ugly, second only to Birmingham in its sleazy grayness, but today it seemed as though the local dignitaries had given some thought to scrubbing up the main streets. Otherwise it looked the same: the downtown section still looked plain and uninspired; the state capitol still bore only the flags of Alabama and the Confederacy, and its bone-white façade gleamed as immaculately as before under the warm sun.

Entering the gates at St. Jude, we saw that cars were leaving every minute to add more people to the march, which by now was less than a couple of miles away.Bob Sack, Susan Ladmer and I got out while Peter Fuchs and my brother Alvin went off to dispose of the car, arranging to meet us at the gate entrance three hours later. After traipsing a few yards through the mud, we were shuttled by a staff member into an overcrowded car, which immediately pulled back onto Highway 80 and headed for the march.

We were let off at the end of the procession (which by now included about two thousand people) and began to march with the others. The rain had fully stopped by now and everyone seemed to be in good spirits; there was a great deal of singing, and the pace of most of the marchers was brisk. The one truly outstanding quality of the crowd was its diversity -– the people we passed and walked alongside ofranged all the way from Brooklyn housewives to Negro children from Selma. Judging from the different ages, professions, personalities and kinds of dress it seemed to be a genuine American cross-section; the only things that we all seemed to have in common were our convictions that led us to participate in the march. There was even something faintly grotesque about the hodgepodge we comprised, a certain incongruity to the mixture of types that contributed a real sense of excitement to the march. We were Everyone, the American people, not a stray bunch of outsiders on the fringe of American life. The federalized state troopers looked, in fact, like members of another planet in their painfully contracted, noncommittal faces; they stood along the road singly and in pairs, staring stiffly ahead as though nothing short of disaster could wrench an emotion out of them.

As I was later to learn, the Thursday had little in common with the march that left Selma on Sunday. Many of the marchers who had traveled the whole fifty miles assured me that the earlier days had been sheer hell, that the heckling and exhaustion had made the trek more of an ordeal than a celebration. The gaiety that followed those days often made me feel that our participation was something of a cheat; the others had worked long and hard for their meal and we were stepping in at the last minute for a free dessert.

But that knowledge was to come later, and at the present we felt thoroughly virtuous about our role in the march. We were moving through a Negro neighborhood now, which meant that our audience was basically a sympathetic one; as we passed a Negro school that had recently let out, it was interesting to see a gradation in the children’s faces that went from suspicion to curiosity to approval to outright enthusiasm. Unlike the state troopers, there wasn’t a passive face in the bunch. Many of the schoolchildren waved to us cheerfully and we waved back; a few stepped off the curb to join in with us. “What yall do-in?” a little Negro boy asked me as he leaped into the procession. We tried to explain some of it to him and he laughed ecstatically. “Montgom-rih ain’t nevah gonna be the same again!”a woman shouted to us from a front lawn. “No-sir,” a teenager shouted back. “No-ma’m, it sure ain’t!”

Some of the marchers were smeared with a white lotion to protect against sunstroke; a few actually fainted from exhaustion and from time to time we would hear an ambulance scream past us. Appointed marshals wearing blue armbands would run along the edge of the march and exhort us like carnival barkers – “Six abreast, keep it six abreast and don’t fall back, free-dom, free-dom,” serving as combination drill sergeants and inspired cheerleaders before running off to see about another segment of the crowd.

When we marched onto the grounds of St. Jude a few minutes later, the liveliest of the marchers were still unready to unwind, and they marched directly into one of the circus tents and started to clap out a freedom chant; two hours later, when I happened to enter the tent again, I noticed that the chant was still going strong.

For the rest of the afternoon we milled around in the steadily accumulating crowd and talked to other marchers. There were clearly people present from everywhere — bankers from Michigan, students from California, business men from the Midwest, teachers from New England, ministers from the South. The overall composition seemed to be mainly oriented towards the middle-class, although to say this of any0 American group does not make it very descriptive. One could quickly establish a rapport with anyone else without awkwardness or self-consciousness; I was especially surprised to find no traces of animosity towards white liberals on the part of Negroes. animosity of the sort that frequently manifests itself in the North in such areas as the plays of Leroi Jones and certain chapters of S.N.C.C. The commonest type ofintroduction was, “Where are you from?” Between high school and college students, a frequent conversation opener was, “Did you tell your parents?”

Suppers began to be distributed at four o’clock. The fifty-milers were given priority over the others, but once the distribution was in full swing there was no evidence of impatient waiting or pushing. Paper bags containing sandwiches, fruit and cookies were given out to whoever wanted them: many people who had brought their own food shared it with other marchers. A stocky Negro man stood with a few helpers on an improvised platform littered with cans and jars of food. loaves of bread, and sandwiches wrapped in cellophane, opening cans as they were handed to him and passing them down to the people below. “Who wants the juice fo I take out the peaches?” he called down, and a small line of Negro schoolgirls shot up their hands. With meticulous care he poured out the juice into paper cups and handed them out with a grin.

The entertainment rally that night was scheduled to start around eight but was delayed for about an hour and a half; when the program did begin, confusion reigned for the first hour while Harry Belafonte, the emcee, tried to get onlookers off the stage and technicians were trying to set the amplifiers at the proper level. Once the program got onto its feet it progressed smoothly until it ended two and a half hours later. The list of celebrities ranged from Leonard Bernstein to Nipsey Russell; there is little point in recounting the entire list here* except to mention that it probably constituted the most impressive entertainment program ever presented in Alabama and, ironically, was taking place on a muddy field rather than a concert hall. The leading white citizens of Montgomery or Birmingham could not have attracted so many “names,” unsolicited or otherwise, but it was pleasing to know that the Negroes of Selma could. Along with President Johnson’s quote of “We Shall Overcome” in his recent speech before the Senate, the rally seemed to portend an important new trend in the civil rights movement: contrary to the attitudes that prevailed before, the members of the movement were now recognized as part of the status quo. The Establishment had done more than take us under their wing; they had fully committed themselves to joining us.

We slept for most of that night on the muddy field, aided by ponchos and blankets. We had set down our gear several hours before, and had complete confidence (that was not violated) that we could leave it there unguarded for hours at a time and not worry about theft. We met with a light drizzle around three a.m. and shortly afterwards were woken again by a staff member who asked us to meet at the road with some of the others so we could be taken to new sleeping quarters. After about thirty minutes of waiting, we were herded into a large truck and taken to a Negro church that lay about a half mile away from St. Jude by a dirt road.

We relocated our sleeping gear on a narrow patch of ground on the side of the Church; in the adjacent yard a rooster w.as crowing repeatedly, which made it apparent, along with the steady flux of talk that murmured inside the church and out, that this was not a night for sleeping. Three of us stepped into the church and saw bodies stretched everywhere – on the pews, in the aisles, in every corner where there was space to sit. Directly below the altar was a table bearing hot coffee and cookies for anyone who felt like having any. Shortly after dawn, we were offered the use of a hose to wash our faces by a man who lived next door to the church, and a few minutes later we walked back to St. Jude and waited for the march to begin.

The Thursday march, like the rally the previous night, began much later than its scheduled time (an unpredictability that prompted one racist Alabama newspaper to coin the term C.P.T. –- meaning “Colored People’s Time” – in reference to various scheduled events connected with the march). We had originally thought that the march to the state capitol would move directly down Highway 80, but it turned out to be routed quite differently; we walked instead directly through the Negro section of Montgomery, which gradually became a lower-class, then a middle-class white district, finally entering the main street of the business section which led directly to the capitol.

Our routing seemed to be strategically worked out in two ways: by passing through the Negro section first, we were obviously making a strong impression on the Negro community of Montgomery; this was apparent enough from the amount ofenthusiasm we encountered on our way to the city. A secondary benefit of this planwas the effect this enthusiasm had on the marchers themselves; by the time we reached downtown Montgomery, there were plenty of immediate reasons for us all to be in good spirits.

Negroes waved to us from their front lawns, from the curbs and from the sidewalks. Scores of children sat perched on porch railings like crows, raising their hands in unison to us as we passed. A few of the Negro children in the march became worried about possible repercussions of their participation, and I saw a few drop out during the first few blocks, but these were only a few, and the general impression was that there were more people joining us along the way than leaving us.

As we entered the white neighborhood, the faces of the observers became passive and impenetrable. I expected to see several looks of overt hostility, but there were not very many; most of the faces appeared to be caught in stalemates between opposite reactions that resulted in bland expressions. To display any appreciation for what we were doing (and we did receive a small number ofapproving looks from white observers) meant alienation from their friends and neighbors; but to display any hatred for us meant conforming to a national stereotype of the white Southerner, an image that the white bystanders seemed just as eager to avoid.

There was a curious unreality about the whole experience of marching through Montgomery. Figuratively speaking. we were all looking directly into the television cameras and the white citizens were looking away, but neither of us was really looking at each other with any scrutiny. It seemed at times that Montgomery was not a city at all but an elaborately constructed set built for the national news media, a façade that represented Montgomery to the rest of the country but not a real place in its own right. On the day of the march, the leading Montgomery newspaper published a two-page ad urging citizens to stay away from the march and avoid any agitation of the marchers; coupled with this plea, predictably, was a complete repudiation of the validity of the march, but it was a kind of repudiation that exhorted the citizens of Montgomery to exercise patience and restraint – and from the look of our audience, it seemed that this ideal was pretty well adhered to.

Our arrival at the state capitol was the climax of the march, and everything that followed seemed less important. Most of the people were too tied to listen to the speeches with any close concentration, and the general look I saw around me was one of weary satisfaction that we had finally arrived. As we looked behind us down the hill and saw thousands more converge on the capitol, we were able to maintain the easy illusion that today we owned the city of Montgomery; it was not very comforting to think of how any of us might feel standing alone on the same street the following day.

II

One disillusioning fact about the march for me was that I had felt that the mere sight of twenty-five thousand people marching for what they believed in would carry a certain conviction to the white people of Alabama. One look at the slanted news coverage in my hometown (Florence, Alabama) convinced me that this effect would be minimal if present at all. It seemed that our march had had a considerable effect on the rest of the country, but to much of the state of Alabama, who questioned our sincerity, our motives, and our morals, we were still little more than an oversized group of parading beatniks. (2013 note: To this day, I recall that at least one prominent Southern newspaper at the time maintained that many of the marchers had decided to participate in the event because of the free meals.)

Two days after the march, we spent a somewhat frustrating three hours talking to a reporter in Florence who had heard about most of the event. During the first hour, we all felt ourselves on the edge of exploding, and the reporter smiled back at us with relaxed geniality and stuck firm to his convictions. In defense of a headline that the march was overrun by beatniks, he told us that he had talked to several marchers who were indeed beatniks. I asked him what a beatnik was. He replied, “Well I couldn’t give you an all-time definition, but I would say a fella with a beard and scraggly hair.” I asked him what a female beatnik was. He laughed at that. “Well I don’t know,” he said, “you got me on that one.”

A great deal of our conversation proceeded in this fashion. The reporter told us that he knew “for a fact” that the Northern press had unfairly distorted the march, that many Northern reporters had told him personally that they had left out unfavorable details about ,the march in their stories in order to give a sympathetic picture. “Now I believe in tellin the whole truth,” he said. We asked him if only unfavorable details constituted the “whole truth”, and he smiled at us and said, “Well, I told it the best way I could. You take the Northern papers, they were tellin it the way they wanted to see it, but I was only reportin on what I saw.”

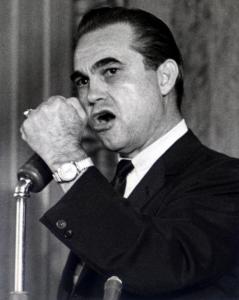

The unavoidable resentment that many white Alabamians now feel about the march and other demonstrations is not simply racism (although it occasionally sounds that way in the press and in public announcements); a considerable part of it is directed against outside intervention, federal and otherwise. The uniqueness of a George Wallace and the source of his state-wide popularity is not racism — that has been used by essentially every Alabama politician, popular and unpopular, during the last few decades. What provokes Wallace’s enthusiastic following in Alabama is his hostility to the federal government, his angry contention that Alabama is not going to be “pushed around” any longer. I had an opportunity to hear one of his campaign speeches in my hometown several years ago when he was running for governor, and I remember that his speech was seething with hate, but nine-tenths of it was directed at the federal government and the North (which most Southerners see as being almost identical entities) rather than the Negro.

The reasons for Alabama’s endorsement of this hostility are easy enough to understand. For generations the state has suffered from an acute inferiority complex in national terms; nearly every Alabamian knows that his state is retarded economically, educationally, and culturally. The one factor about his state that he can cling to with pride is his tradition, and it has been George Wallace’s political coup to confuse this tradition with the whole question of state’s rights. There is something exciting to a white Alabamian about seeing his representative standing in front of the state university and screaming his head off before the rest of the nation; in Wallace the white Alabamians have a voice to give perfect vent to their frustrations. It is significant, however, that when we arrived at the state capitol, Wallace did not step out and scream at us; he is apparently much more assured when he can scream at abstractions. Perhaps it is also significant, and doubly tragic, that when the marchers stood up and lifted their American flags to sing the Star Spangled Banner, the Alabama Legislature, which sat on the steps of the capitol, remained seated.

*Just a partial list, culled from my book Moving Places: Joan Baez, James Baldwin, Mai Britt, Sammy Davis, Jr., George Kirby, Peter Lawford, Mike Nichols and Elaine May, Tony Perkins, Nina Simone (singing “Mississippi Goddam,” which I heard at this event for the first time), Frank Sinatra, and Shelley Winters. And, unless my memory is playing tricks on me, I believe that Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward appeared also.