From Sight and Sound, Winter 1982/1983, and reprinted in my collection Placing Movies. It was initially commissioned by Peter Biskind for American Film, who decided not to run it and paid me a kill fee, so I sent it next to Penelope Houston, who accepted it without hesitation. Originally, this piece was designed to be run with my translation of a brief, early piece by Barthes (“Au Cinemascope,” originally published in Les Lettres Nouvelles, February 1954). To my frustration, after Sight and Sound secured the rights to run this piece, they wound up omitting it due to lack of space, but it has subsequently appeared online in at least two places: here and here (the latter on this site). — J.R.

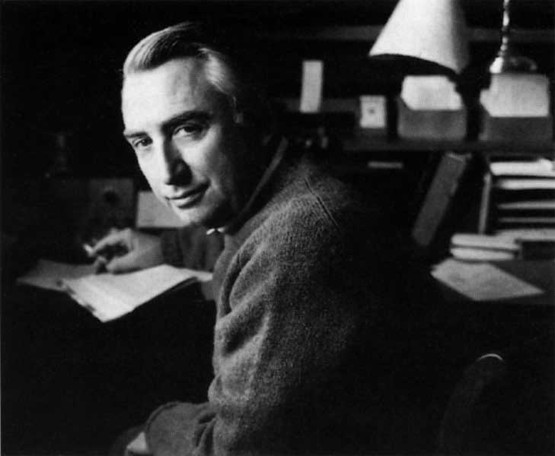

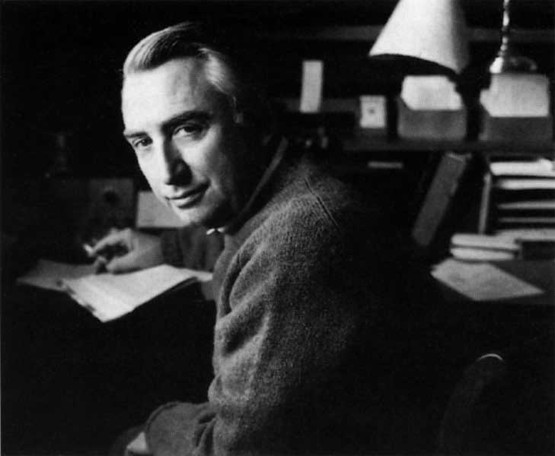

One reason for looking at the late Roland Barthes’ writings about film is that we all tend to be much too specialized in the ways that we think about culture in general and movies in particular. Far from being a film specialist, Barthes could even be considered somewhat cinephobic (to coin a term), at least for a Frenchman. Speaking to Jacques Rivette and Michel Delahaye in 1963, he confessed, “I don’t go very often to the cinema, hardly once a week” — inadvertently revealing the French passion for movies that can infect even a relative nonbeliever. Read more

Written for the catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna (June-July 2017). — J.R.

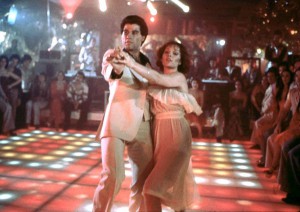

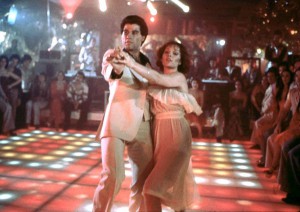

Dave Kehr has aptly described it as a “1977 update of Rebel Without a Cause” and a “small, solid film, made with craft if not resonance”. But it’s also a dance musical and the hit that catapulted John Travolta to stardom after a brief career in theater and on television (notably on Welcome Back, Kotter).

There’s a manic-depressive side to most musicals—a tendency to navigate mood swings from depression to exhilaration and back again–that’s observable in everything from Swing Time to The Band Wagon to La La Land. Saturday Night Fever takes that pattern to an unusual extreme in the way it oscillates between a view of Brooklyn’s Bay Ridge neighborhood as a version of hell on earth whose residents devote all their waking hours to humiliating one another and the heavenly, utopian lift and glory of dancing at one of its discotheques called 2001 Odyssey. Most people who fondly remember this movie are likely to focus on the latter and think less about the former, but it’s the relation between these two registers that gives the movie its energy.

The screenplay by Norman Wexler (Joe, Serpico, Mandingo) is derived from an article in New York magazine (“Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night”) whose author, British rock critic Nik Cohn, admitted two decades later was more invented than observed. Read more

An essay commissioned by Masters of Cinema in the U.K. for their DVD of Fritz Lang’s Spione, released in 2005. This is reprinted in my collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition (University of Chicago, 2010). — J.R.

If Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen (1924) anticipates the pop mythologies of everything from Fantasia to Batman to Star Wars, his master spy thriller of four years later seems to usher in some of the romantic intrigues of Graham Greene, not to mention much of the paraphernalia of Ian Fleming, especially in their movie versions. No less suggestively, the employments of paranoia and conspiracy by less mainstream artists such as Jacques Rivette (Out 1) and Thomas Pynchon (Gravity’s Rainbow) seem rooted in the seductively coded messages, erotic intrigues, and multiple counter-plots of Spione.

One is also tempted to speak of Alfred Hitchcock, who certainly learned a trick or two from Lang —- though in this case the conceptual and stylistic differences may be more pertinent than the similarities. One could generalize by saying that Hitchcock is more interested in his heroes while Lang is more interested in his villains, and the different approaches of each director in soliciting or discouraging the viewer’s identification with his characters are equally striking, especially if one contrasts the German films of Lang with the American films of Hitchcock. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 27, 2004).

On February 12, 2018, Ken Jacobs sent me the following email:

Dear Jonathan,

I first came upon writing on STAR SPANGLED TO DEATH a week ago. Sorry.

Appreciate what you had to say except, naturally, for your take on my Muslim comment. So I must’ve failed to make clear my despising of all religions with their bloody track records. I go so far as to consider the to-do about Nazis overblown: a momentary political organization that, employing Ford up-to-date industrial methods, accomplished the actual near-fulfillment/”final solution” to 2 000 years of strenuous Christian degradation, torture and outright slaughter of Jews. “Race” had just been invented maybe a century earlier but murdering Jews was an enduring Christian project. (Nor were Nazis killing any other “race”.) A fact to remember about WW2: Christians murdered Jews. A land war coupled to a religious “war” and the war they were allowed to win by USA as long as they could keep costing the Soviets. Don’t get me started….

I’m remembering one line in the film about “a bedtime story gone amok”. That is my take on these force-fed beliefs given helpless children wired up to believe, needing to believe if they’re to survive (“no, you can’t run into traffic”).

Read more