Written for FIPRESCI, specifically for their web site,from Seattle. –J.R.

The Undermining of Intimacy: Home and Everyone Else

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

As different as they are in other respects, one interesting facet shared by two tragicomic European features included in the New Directors Showcase at the Seattle International Film Festival, Ursula Meier’s Home (2008) and Maren Ade’s Alle Anderen (Everyone Else, 2009), is that they both show the gradual deterioration of intimate relationships that starts to occur between or among individuals in isolation from “everyone else”, after they start to become less isolated. In both cases, contact with the outside world seems to operate as a kind of contamination, although the possibility is posed in each case that the

sickness is already present from the outset, but needs the objectification provided by the outside world in order to become fully evident.

Meier’s Home, a second feature, introduces us to an eccentric but lovingly and happily close-knit family living in the country next to an unfinished superhighway — mother (Isabelle Huppert), father (Olivier Gourmet), older daughter (Adéläide Leroux), younger daughter (Madeleine Budd), and son (Kacey Mottet Klein) — who are gradually driven bonkers by the sound, pollution, and lack of privacy brought by passing vehicles once the superhighway opens. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 29, 1992). . — J.R.

A TALE OF THE WIND

**** (Masterpiece)

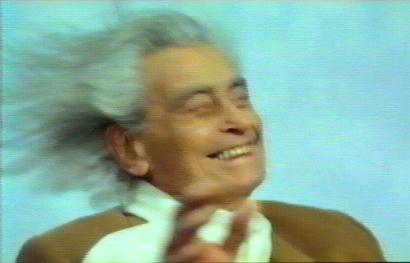

Directed by Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan

Written by Loridan, Ivens, and Elisabeth D.

With Ivens, Loridan, Han Zenxiang, Liu Zhuang, Wang Delong, Wang Hong, Fu Dalin, Liu Guillian, Chen Zhijian, Zou Qiaoyu, and Paul Sergent.

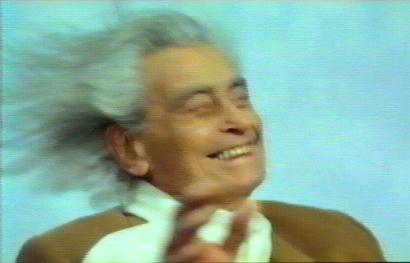

The Old Man, the hero of this tale, was born at the end of the last century, in a country where man has always striven to tame the sea and harness the wind. Camera in hand, he has traversed the 20th century in the midst of the stormy history of our time. In the evening of his life, at age 90, having survived the various wars and struggles that he filmed, the old filmmaker sets off for China. He has embarked on a mad project: to capture the invisible image of the wind.”

That’s my translation of the French opening title of A Tale of the Wind. It follows the credits, which accompany shots of a plane flying through the clouds and Michel Portal’s primitive-modern jazz score for woodwinds and percussion. After the opening passage the giant blades of a Dutch windmill fill the screen, followed by shots of a little boy in an aviator suit on a windswept lawn, apparently preparing to fly away on a small plane to China, calling to his mother. Read more

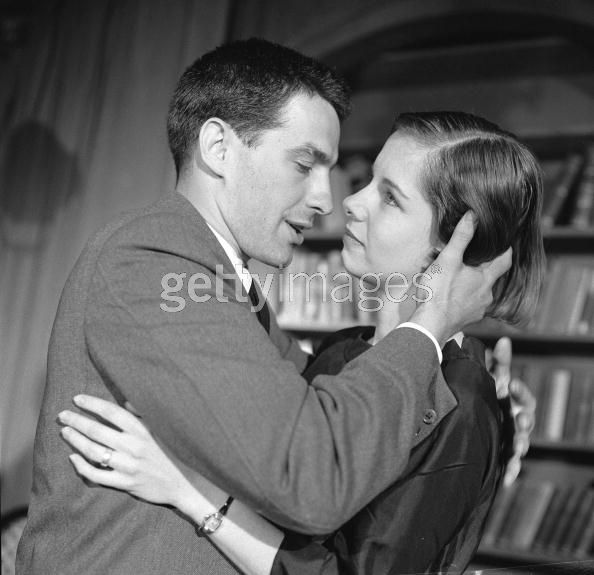

1957 was clearly a bumper year for John Frankenheimer on Playhouse 90: the eleven shows that he directed included The Ninth Day (January 10, the only one I can faintly recall having seen at the time), The Comedian (February 14), The Last Tycoon (March 14), and then a second F. Scott Fitzgerald adaptation, which I’ve just seen for possibly the first time, Winter Dreams (May 23), costarring John Cassavetes and Dana Wynter. (That’s Phyllis Love, another costar, in the above illustration.) All of which probably helps to explain why I considered Frankenheimer an auteur before I ever used that term, during my early teens, for his work on Studio One as well as Playhouse 90.

As masterful in way as The Comedian and The Last Tycoon, Winter Dreams departs from Fitzgerald’s material a lot more than The Last Tycoon by concentrating on the sort of details that the original story leaves out, involving (for instance) the hero’s parents and college room mate, and by ending many years before the story does. (The script is by James B. Cavanagh.) The tone is quite different, too; Fitzgerald’s 1922 story is a reverie whereas the adaptation is much more obviously obsessional. Read more

What’s most disconcerting about Jane Campion’s affecting evocation of Fanny Brawne and John Keats, which I caught up with tonight in Edinburgh, is that it has an exquisite soundtrack for me — erotic, tactile, essentialist in the best sense — only when Keats’ poetry remains unheard. Whether it’s being recited by Ben Wishaw as Keats or by Abbie Cornish as Brawne, the issue isn’t how or how well it’s being recited, which I have no particular quarrels with, but the fact that it gets recited at all. I was admittedly grateful in a way to hear Wishaw recite all of “Ode to a Nightingale” over the final credits, despite the distracting musical accompaniment, even while a good half of the audience was leaving the theater, because there, at least, it wasn’t competing with Campion’s filmmaking. But I’m less sure about the other employments of Keats’ writing in the film, even though the letters arguably seem more justifiable than the poetry, at least from a narrative standpoint.

One of Campion’s strongest suits has always been her eroticism, and the best part of A.O. Scott’s review in the New York Times (as it often is, for him as well as for Manohla Dargis) comes not in the review proper but in the squib at the end appended to the MPAA rating: “It is perfectly chaste and insanely sexy.” Read more

It’s been ten days since I saw the new Michael Moore film, when I was in New York. Then and now, it struck me as being inferior to Sicko, Fahrenheit 9/11, and Bowling for Columbine, yet singular none the less in a way that only a Michael Moore film can be, less for its own qualities (cinematic, political, aesthetic) than for the unique cultural function it has. In a country that essentially has no news, only a series of screeds designed to either stroke or else violently refute or ignore one’s own particular biases (pace Rachel Maddow, cued laughs and all), Moore’s movies wind up teaching us things even if we don’t see them because of the way that certain second-hand kernels of information get filtered down to us. And I certaiinly include myself in this process. Capitalism: A Love Story taught me several things I had known either nothing or very little about — perhaps most importantly, Franklin Roosevelt’s call for a “second Bill of Rights” shortly before his death that ensured the right of individuals to have a job, a decent wage, and health care. Seeing that clip of FDR giving that long-suppressed and forgotten speech is reason enough to see this film. Read more