This appeared in the November 18, 1988 Chicago Reader. I’d probably rank this film higher now. — J.R.

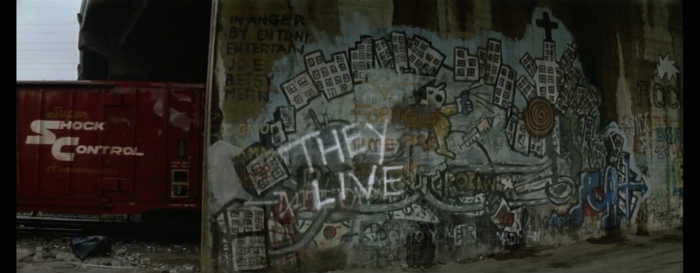

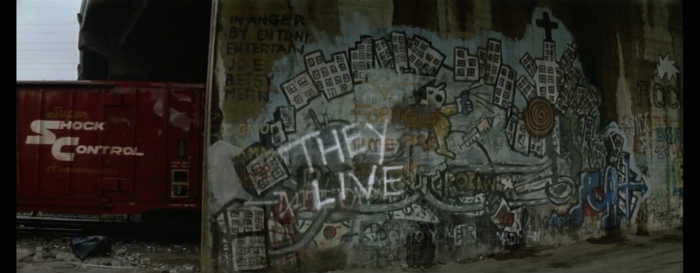

THEY LIVE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John Carpenter

Written by “Frank Armitage” (John Carpenter)

With Roddy Piper, Keith David, Meg Foster, George “Buck” Flower, Peter Jason, and Raymond St. Jacques.

John Carpenter has managed to remain one of the few genuinely personal writer-directors left in genre moviemaking, having returned to relatively low-budget features with last year’s Prince of Darkness after the debacle of Big Trouble in Little China. From his clean ‘Scope compositions to his throbbing minimalist scores, he projects a simplicity of conception and a usually deft approach to story telling and straight-ahead action that are both refreshing and reassuring in an era of filmmaking when these modest virtues can no longer be taken for granted. As a disciple of Howard Hawks, he might even be said to preserve a scaled-down version of some of the familiar Hawks trademarks: cranky individualist heroes, flaky male/female relationships, camaraderie among professionals, confined spaces, and usually clear lines of demarcation between friends and foes.

All of these qualities are present to some degree in They Live, a paranoid science-fiction thriller about alien invaders loosely based on a short story by Ray Nelson. Read more

Written for the catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna (June-July 2017). — J.R.

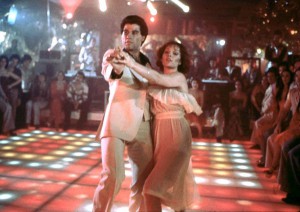

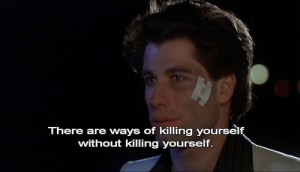

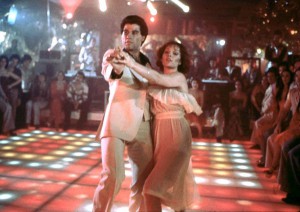

Dave Kehr has aptly described it as a “1977 update of Rebel Without a Cause” and a “small, solid film, made with craft if not resonance”. But it’s also a dance musical and the hit that catapulted John Travolta to stardom after a brief career in theater and on television (notably on Welcome Back, Kotter).

There’s a manic-depressive side to most musicals—a tendency to navigate mood swings from depression to exhilaration and back again–that’s observable in everything from Swing Time to The Band Wagon to La La Land. Saturday Night Fever takes that pattern to an unusual extreme in the way it oscillates between a view of Brooklyn’s Bay Ridge neighborhood as a version of hell on earth whose residents devote all their waking hours to humiliating one another and the heavenly, utopian lift and glory of dancing at one of its discotheques called 2001 Odyssey. Most people who fondly remember this movie are likely to focus on the latter and think less about the former, but it’s the relation between these two registers that gives the movie its energy.

The screenplay by Norman Wexler (Joe, Serpico, Mandingo) is derived from an article in New York magazine (“Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night”) whose author, British rock critic Nik Cohn, admitted two decades later was more invented than observed. Read more

From the Chicago Reader, October 29, 1995.

As the Chicago International Film Festival moves into its second week, two more films with distributors have been added to the list. Persuasion — a thoughtful, intelligent adaptation of the Jane Austen novel that provides a welcome alternative to Merchant-Ivory — is replacing Deathmaker and is being handled by Sony Pictures Classics. Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead, filling the “surprise” film slot, is on all counts the dumbest Hollywood movie I saw in Cannes last May — an egregious Tarantino spin-off with everything the mainstream press is screaming for: a simple (even stupid) contrived plot, intimations of deranged and nonsensical violence, macho stances, movie stars, a fancy title, and the Miramax logo. It has nothing to do with reality and everything to do with someone pointing at Reservoir Dogs and saying, “Let’s have another one of those.” Under the circumstances, I guess the performances are OK.

Last week I suggested that the focus of this year’s retrospective, Lina Wertmuller — the recent recipient of the festival’s Golden Hugo for lifetime achievement — was a bizarre choice that might have been made interesting if the festival had issued a monograph explaining why her work was still worth defending or had some special relevance to the 90s. Read more

My “Global Discoveries on DVD” column for the Winter 2015 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

For now the truly shocking thing was the world itself. It was a new world. and he’d just discovered it, just noticed it for the first time.

— Orhan Pamuk, The Black Book

I: Some Conspicuous Absences

As a rule, this column has been preoccupied with what’s available in digital formats, but I’d like to start off this particular quarterly installment with a list of some of the things that aren’t available, at least not yet. This alphabetical checklist is by no means even remotely exhaustive and is entirely personal, based on a few of my recent experiences:

Alain Resnais (two titles): The two most glaring lacunae here are Resnais’ first major film and the last of his features, neither of which can be found yet with English subtitles. Les Statues meurent aussi (Statues Also Die, 1953), written by Chris Marker, a remarkable half-hour essay film about African sculpture, also qualifies as his own first major film work –- its beautiful and corrosive text is the first one Marker chose to print in his (still untranslated) two-volume 1967 collection Commentaires. It appears that the film’s unavailability on DVD or Blu-Ray in subtitled form can be attributed to two forms of censorship -– French political censorship when the film first appeared (which lasted for several decades), and North American capitalist censorship (which is apparently still in force). Read more

I’d like to beat the drum a little for a terrific new book just published by University of California Press, Catherine Benamou’s It’s All True: Orson Welles’s Pan-American Odyssey, which is far and away the definitive book on It’s All True, Welles’s doomed documentary project about Latin America in the 1940s. Maybe the fact that the same publisher is bringing out a book of mine about Welles in a couple of months gives me a special interest in the subject; I should also note that Benamou, who’s been working on her book for well over two decades, is an old friend. (She also arranged recently for the purchase of two major Welles collections by the University of Michigan, which are going by the name “Everybody’s Orson Welles.” I was privileged to be the first visitor to this mountain of material in Ann Arbor last summer, which is where I collected the stills used on my own book jacket.)

Some readers may be put off a bit by Catherine’s academic language, but the fact remains that so much fresh and even startling information is available here—information that corrects countless myths—that if you care about Welles at all, you can’t afford to ignore this book.

Read more

This originally appeared in the twelfth issue of Camera Obscura (Summer 1984). I’m delighted that a DVD of Sally Potter’s overlooked, neglected, and scandalously undervalued masterpiece is finally available, from the British Film Institute. I wrote a short essay for the accompanying booklet. –J.R.

The Gold Diggers: A Preview

Sally Potter’s much heralded British Film Institute production has been encountering a lot of resistance since it premiered at the London Film Festival late last year. When I saw it at the Rotterdam Film Festival in early February, its presence even there was regrettably nominal: screened only once, and in the Market rather than as a festival selection, it was received rather coolly, and many of the critics present left well before the end. Finding the film visually stunning, witty, and pleasurably inventive throughout, I can only speculate about the reasons for the extreme antipathy of my colleagues.

Historically, The Gold Diggers demands to be regarded as something of a proud anomaly. While it contains many familiar echoes of avant-garde performance art (including music, dance, and theater), its only recognizable antecedent in the English avant-garde film tradition appears to be Potter’s own previous Thriller. (An English language film which is international in conception as well as execution, it is marginal in the best and most potent sense of that term.) Read more

Edward Yang’s most accessible movie (2000) follows three generations of a contemporary Taipei family from a wedding to a funeral, and while it takes almost three hours to unfold, not a moment seems gratuitous. Working with nonprofessional actors, Yang coaxes a standout performance from Wu Nien-jen as N.J., a middle-aged partner in a failing computer company who hopes to team up with a Japanese game designer and who has a secret rendezvous in Tokyo with a girl he jilted 30 years earlier; other major characters include the hero’s eight-year-old son, teenage daughter, spiritually traumatized wife, comatose mother-in-law, and debt-ridden brother-in-law. The son, who becomes obsessed with photographing what people can’t see, may come closest to being a mouthpiece for Yang, who seems to miss nothing as he interweaves shifting viewpoints and poignant emotional refrains, creating one of the richest families in modern movies. In Mandarin with subtitles. 173 min. (JR) Read more

The strangest by far of Jacques Rivette’s films (1976), and perhaps the last gasp of the modernist strain that infused his work from L’amour fou to Out 1 to Celine and Julie Go Boating, this is a violent and unsettling fusion of a female pirate adventure (filmed on some of the same locations used for The Vikings and inspired in part by Lang’s Moonfleet, but set in no particular place or period), mythological fantasy, Jacobean tragedy (with many lines borrowed from Tourneur’s Revenger’s Tragedy), experimental dance film (with live improvised music from a talented trio of musicians), and personal psychodrama. The eclectic cast includes Geraldine Chaplin, Bernadette Lafont, Kika Markham (Two English Girls), and a few members of Carolyn Carlson’s dance company. While the mise en scène and locations are often stunning, the film seems contrived to confound conventional emotional reactions of any sort. It’s a movie where the casual slitting of someone’s throat and the swishing sounds of Lafont’s leather pants are made to seem equally relevant — a world apart from Rivette’s more recent La belle noiseuse. Yet Rivette’s feeling for duration, immediacy, and moods of menace are fully present here, and days or weeks after you see this chilling conundrum of a movie, sounds and images may come back to haunt you. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 21, 2000). My thanks to my editor on this piece, Kitry Krause, for (among many other things) coming up with my title. — J.R.

Time Regained ***

Directed by Raul Ruiz

Written by Gilles Taurand and Ruiz

With Marcello Mazzarella, Catherine Deneuve, Emmanuelle Béart, Vincent Perez, John Malkovich, Pascal Greggory, Marie-France Pisier, Christian Vadim, Arielle Dombasle, Chiara Mastroianni, and the voice of Patrice Chéreau.

[A few years ago], I refused to direct Remembrance of Things Past. I wrote to the woman producer [Nicole Stéphane] that no real filmmaker would allow himself to squeeze the madeleine as though it were a lemon and in my opinion only a film butcher would have the nerve to put Proust through the mincer.

A few weeks later she obtained the agreement of the Verdurin salon, that is to say, René Clement. Come to think of it, is Proust burning in [the book-burning fires of my film] Fahrenheit 451? No, but this omission will soon be corrected.

— François Truffaut, “The Journal of Fahrenheit 451” (1966)

I read Remembrance of Things Past all the way through more than 35 years ago, shortly before Truffaut registered his scorn about the very notion of a film version (Stéphane eventually got the film made in 1984, Volker Schlšndorff’s dispensable Swann in Love). Read more

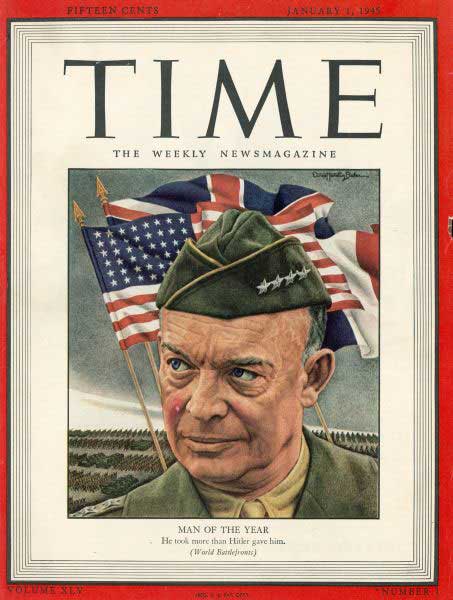

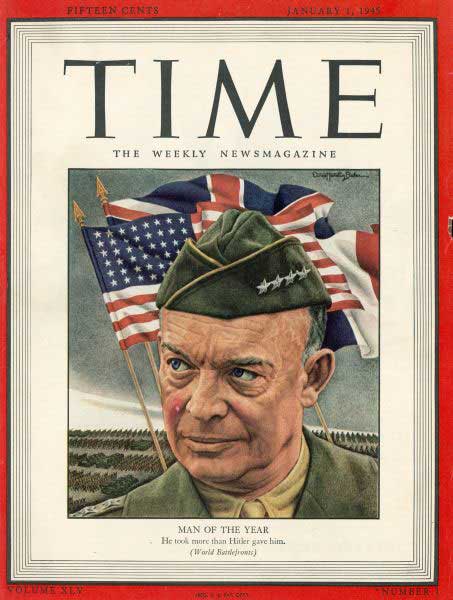

- Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. This is not a way of life at all in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.

- –Dwight D. Eisenhower, from a speech to the American Society of Newspaper Editors, April 16, 1953

Read more

Written for FIPRESCI, specifically for their web site,from Seattle. –J.R.

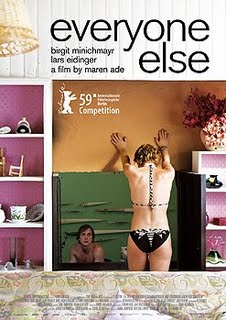

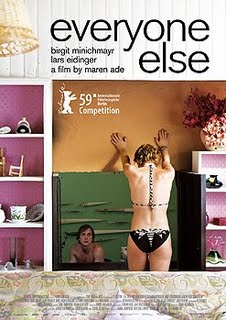

The Undermining of Intimacy: Home and Everyone Else

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

As different as they are in other respects, one interesting facet shared by two tragicomic European features included in the New Directors Showcase at the Seattle International Film Festival, Ursula Meier’s Home (2008) and Maren Ade’s Alle Anderen (Everyone Else, 2009), is that they both show the gradual deterioration of intimate relationships that starts to occur between or among individuals in isolation from “everyone else”, after they start to become less isolated. In both cases, contact with the outside world seems to operate as a kind of contamination, although the possibility is posed in each case that the

sickness is already present from the outset, but needs the objectification provided by the outside world in order to become fully evident.

Meier’s Home, a second feature, introduces us to an eccentric but lovingly and happily close-knit family living in the country next to an unfinished superhighway — mother (Isabelle Huppert), father (Olivier Gourmet), older daughter (Adéläide Leroux), younger daughter (Madeleine Budd), and son (Kacey Mottet Klein) — who are gradually driven bonkers by the sound, pollution, and lack of privacy brought by passing vehicles once the superhighway opens. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 29, 1992). . — J.R.

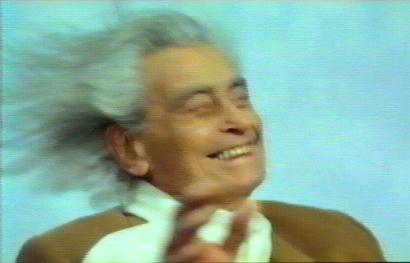

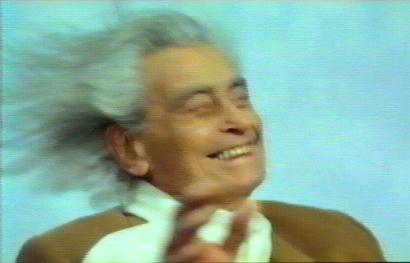

A TALE OF THE WIND

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan

Written by Loridan, Ivens, and Elisabeth D.

With Ivens, Loridan, Han Zenxiang, Liu Zhuang, Wang Delong, Wang Hong, Fu Dalin, Liu Guillian, Chen Zhijian, Zou Qiaoyu, and Paul Sergent.

The Old Man, the hero of this tale, was born at the end of the last century, in a country where man has always striven to tame the sea and harness the wind. Camera in hand, he has traversed the 20th century in the midst of the stormy history of our time. In the evening of his life, at age 90, having survived the various wars and struggles that he filmed, the old filmmaker sets off for China. He has embarked on a mad project: to capture the invisible image of the wind.”

That’s my translation of the French opening title of A Tale of the Wind. It follows the credits, which accompany shots of a plane flying through the clouds and Michel Portal’s primitive-modern jazz score for woodwinds and percussion. After the opening passage the giant blades of a Dutch windmill fill the screen, followed by shots of a little boy in an aviator suit on a windswept lawn, apparently preparing to fly away on a small plane to China, calling to his mother. Read more

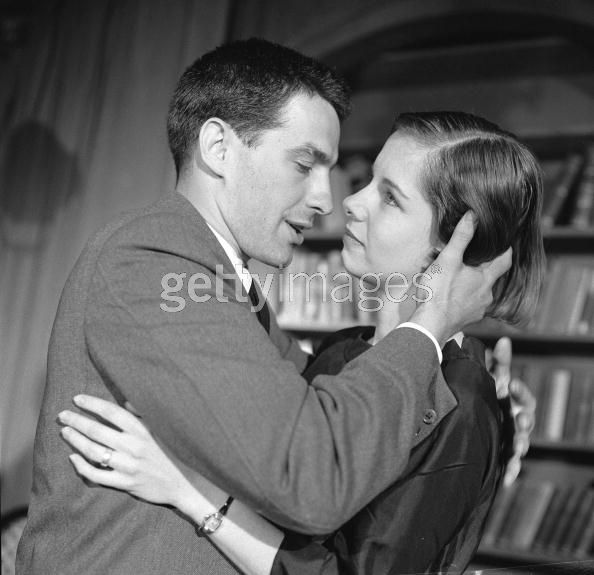

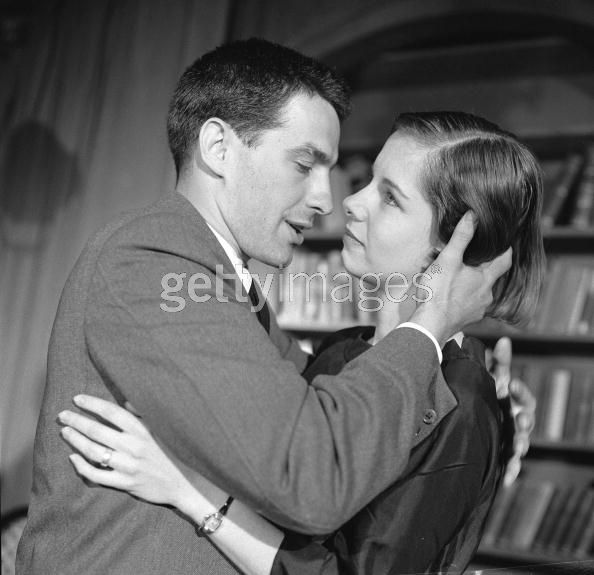

1957 was clearly a bumper year for John Frankenheimer on Playhouse 90: the eleven shows that he directed included The Ninth Day (January 10, the only one I can faintly recall having seen at the time), The Comedian (February 14), The Last Tycoon (March 14), and then a second F. Scott Fitzgerald adaptation, which I’ve just seen for possibly the first time, Winter Dreams (May 23), costarring John Cassavetes and Dana Wynter. (That’s Phyllis Love, another costar, in the above illustration.) All of which probably helps to explain why I considered Frankenheimer an auteur before I ever used that term, during my early teens, for his work on Studio One as well as Playhouse 90.

As masterful in way as The Comedian and The Last Tycoon, Winter Dreams departs from Fitzgerald’s material a lot more than The Last Tycoon by concentrating on the sort of details that the original story leaves out, involving (for instance) the hero’s parents and college room mate, and by ending many years before the story does. (The script is by James B. Cavanagh.) The tone is quite different, too; Fitzgerald’s 1922 story is a reverie whereas the adaptation is much more obviously obsessional. Read more

What’s most disconcerting about Jane Campion’s affecting evocation of Fanny Brawne and John Keats, which I caught up with tonight in Edinburgh, is that it has an exquisite soundtrack for me — erotic, tactile, essentialist in the best sense — only when Keats’ poetry remains unheard. Whether it’s being recited by Ben Wishaw as Keats or by Abbie Cornish as Brawne, the issue isn’t how or how well it’s being recited, which I have no particular quarrels with, but the fact that it gets recited at all. I was admittedly grateful in a way to hear Wishaw recite all of “Ode to a Nightingale” over the final credits, despite the distracting musical accompaniment, even while a good half of the audience was leaving the theater, because there, at least, it wasn’t competing with Campion’s filmmaking. But I’m less sure about the other employments of Keats’ writing in the film, even though the letters arguably seem more justifiable than the poetry, at least from a narrative standpoint.

One of Campion’s strongest suits has always been her eroticism, and the best part of A.O. Scott’s review in the New York Times (as it often is, for him as well as for Manohla Dargis) comes not in the review proper but in the squib at the end appended to the MPAA rating: “It is perfectly chaste and insanely sexy.” Read more

It’s been ten days since I saw the new Michael Moore film, when I was in New York. Then and now, it struck me as being inferior to Sicko, Fahrenheit 9/11, and Bowling for Columbine, yet singular none the less in a way that only a Michael Moore film can be, less for its own qualities (cinematic, political, aesthetic) than for the unique cultural function it has. In a country that essentially has no news, only a series of screeds designed to either stroke or else violently refute or ignore one’s own particular biases (pace Rachel Maddow, cued laughs and all), Moore’s movies wind up teaching us things even if we don’t see them because of the way that certain second-hand kernels of information get filtered down to us. And I certaiinly include myself in this process. Capitalism: A Love Story taught me several things I had known either nothing or very little about — perhaps most importantly, Franklin Roosevelt’s call for a “second Bill of Rights” shortly before his death that ensured the right of individuals to have a job, a decent wage, and health care. Seeing that clip of FDR giving that long-suppressed and forgotten speech is reason enough to see this film. Read more