From the September 1, 1994 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

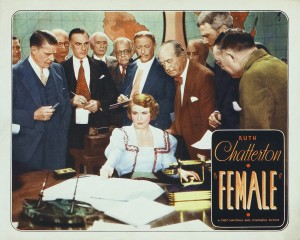

Ruth Chatterton and George Brent, a real-life married couple at the time of this 1933 feature, star as the tyrannical head of a major auto company and the independent-minded guy who comes along to challenge her and win her heart. Before it (and its heroine) abjectly cop out in the closing minutes, this hour-long precode feature offers a bracing feminist fever dream of a young woman commanding a huge corporation and a stable of attractive young men, whom she invites over to her house for one-night stands. Breezily directed by Michael Curtiz and William Dieterle; with Johnny Mack Brown, Ruth Donnelly, and some very sumptuous set design — Depression fantasy of the good life at its most hyperbolic. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From American Film (November 1981). — J.R.

Old Wave Saved from Drowning

By Sandy Flitterman and Jonathan Rosenbaum

Think of French cinema, and the New Wave springs immediately to mind. This association is hardly accidental. History, it is often said, gets written by the victors. And the victories recounted in the standard film histories — whether they are critical successes or box-office triumphs — are inevitably at the expense of other movies, individuals, or social trends that presumably failed to scale the same heights.

But the New Wave, like other movements in film history, is significant not only for what it gave us — films like Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, Godard’s Breathless, and Resnais’ Hiroshima, mon amour — but also for what it took away, for the films it rebelled against, repudiated, buried in the dustbin of history. Now a fascinating new program of forty-six subtitled French films made between 1930 and 1960 helps sketch out the rudiments of just such an alternative history.

This group of films, appropriately entitled “Rediscovering French Film,” has been put together by New York’s Museum of Modern Art in cooperation with the French government and, after premiering in Manhattan this month, is scheduled to travel next year to Washington, Berkeley, Los Angeles, Houston, and Chicago. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 3, 1989). Twilight Time has recently (2014) released this film on Blu-Ray, with many extras. — J.R.

The point of director Jimmy Murakami and screenwriter Raymond Briggs’s rather original English animated feature is to get us to think the unthinkable — to imagine the aftereffects of a nuclear holocaust. But rather than force this bitter pill on us, they create a very funny and believable elderly English couple, Jim and Hilda Bloggs. These two are still mired in memories of World War II, but when nuclear war hits they are eager to do all the proper things and to follow the instructions in the government booklets correctly. Rather than stretch this fable out to a global scale, the filmmakers make all their essential points by sticking to this isolated couple in their country cottage, following them step-by-step through the experience. Aided by a realistic style of animation that incorporates some live action, by occasional stylistic changes that allow for more abstraction in some fantasy interludes, and by the expert speaking voices of John Mills and Peggy Ashcroft, the movie succeeds impressively. It’s rare that a cartoon carries the impact of a live-action feature without sacrificing the imaginative freedom of the pen and brush, but this one does — and does so well that we are even persuaded to accept the didactic framework. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 21, 2005). Alas, I’ve never been any sort of Shakespearean scholar, and if I’d read the devastating take-down of this film by Ron Rosenbaum (no relation) in The Shakespeare Wars, published the following year, I’m sure I would have been far less tolerant….It’s worth adding, however, that Ron Rosenbaum isn’t any sort of Orson Welles scholar when he accepts the 1997 version of his Othello as a “restored” version — or when countless other commentators call the 2014 perpetuation of that version, with Welles’ own choices of music and sound effects replaced by uninformed simulations, any sort of “restoration”. (Welles’ own two versions of Othello — that is to say, with his own soundtracks — were thoroughly suppressed until Criterion eventually released them both.) — J.R.

Director Michael Radford (Nineteen Eighty-Four, Il postino) begins his adaptation of the Shakespeare play with a precise date and a brief documentary about anti-Semitism in 16th-century Venice; this doesn’t have much to do with the playwright or his audience, but it provides a social context for what follows. Al Pacino avoids his usual bombast, giving his Shylock some shading, and Jeremy Irons is fine as Shylock’s legal opponent, Antonio. Read more