From the Chicago Reader (November 20, 1987). — J.R.

The four films to date of independent Chicago filmmaker Peter Thompson form two diptychs: not films to be shown simultaneously side-by-side, but successive works whose meanings partially arise out of their intricate inner rhymes and interactions. Two Portraits (1982), which has already had limited exposure in Chicago, describes the filmmaker’s parents: Anything Else, devoted to Thompson’s late father, combines stop-frame images of him, in an airport and outdoors, with a painful recording of his voice taken in a hospital and a multifaceted verbal portrait delivered by his son; Shooting Scripts juxtaposes the filmmaker’s mother, Betty Thompson, reading from her own diaries with a minimalist view of her sleeping on a beach chair, alternating stop-frames with privileged moments of movement. Together these films create a rich tapestry, but the more recent hour-long pair, Universal Hotel and Universal Citizen (1987), receiving their premiere here, create a still more ambitious and dense interweaving of objective and subjective elements. As Thompson puts it, this diptych deals with three main themes: “the emotional thawing of men by women, the struggle to disengage remembrance from historical anonymity, and nonrecoverable loss.” In the first film, Thompson describes his involved research about medical experiments in deep cold conducted on a Polish prisoner and a German prostitute by Dr. Read more

Written for A Man Called Ermanno: Olmi’s Cinema and Works, published by Edições Il Sorpasso (in Lisbon) in May 2012. A French translation of this essay has been published in Trafic #91, automne 2014. — J.R.

For me, the cinema is a state of mind and a process of analysis from a series of detailed observations.

— Ermanno Olmi, from a 1988 interview (1)

1

Ermanno Olmi first became well known as a filmmaker during the period in the early 1960s when the Nouvelle Vague and, more specifically, François Truffaut’s formulation of la politique des auteurs, were near the height of their international influence. Yet it seems that one factor that has limited Olmi’s reputation as an auteur over the half-century that has passed since then is his apparent reluctance and/or inability to remain type-cast in either his choice of film projects or in his execution of them. Indeed, the fact that he repeatedly eludes and/or confounds whatever auteurist profile that criticism elects to construct for him in its effort to classify his artistry results in a periodic neglect of him followed by periodic “rediscoveries”. And these rediscoveries are confused in turn by the fact that each rediscovery of Olmi’s work seems to redefine his profile rather than build on the preceding one. Read more

Published, in a slightly shorter version, in the August 2014 Sight and Sound. — J.R.

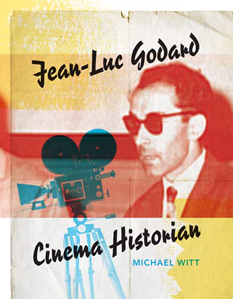

JEAN-LUC GODARD, CINEMA HISTORIAN

By Michael Witt. Indiana University Press, 276pp. £20.65.

paperback, ISBN 9780253007285

Reviewed by Jonathan Rosenbaum

There has been a slew of important books lately devoted to post-60s Godard, including Daniel Morgan’s Late Godard and the Possibilities of Cinema, Jerry White’s Two Bicycles: The Work of Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville, and Godard’s own Introduction to a True History of Cinema and Television, translated by Timothy Barnard — the latter including Michael Witt’s introductory, 55-page ‘Archaeology of Histoire(s) du cinéma’. But none seems quite as durable, both as a beautiful object and as a user-friendly intellectual guide, as Witt’s superbly lucid, jargon-free book about Histoire(s) du cinéma, Jean-Luc Godard, Cinema Historian.

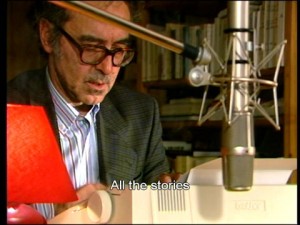

Copiously illustrated with frame enlargements that complement the text without ever seeming redundant, this examination of the philosophical, historical, and aesthetic underpinnings of Godard’s masterwork isn’t only about a four and a half-hour video; it’s also about the work’s separate reconfigurations as a series of books, a set of CDs, and a 35-millimeter feature of 84 minutes (Moments choisis des Histoire(s) du cinéma). Read more