An eye-opening documentary (2003) by Nancy Kates and Bennett Singer about the most sophisticated and charismatic of the civil rights leaders, enhanced by insights about why he became the most neglected. A onetime singer in Josh White’s quartet, the Carolinians, a communist between 1938 and ’41, and a conscientious objector imprisoned during World War II, Rustin (1912-’87) helped to school Martin Luther King in pacifismand persuaded him at an early stage not to own guns. Ultimately Rustin was driven to the margins of the movement for being outspokenly gay and refusing (on tactical grounds) to oppose the war in Vietnam. Without overemphasizing either of these factors, this intelligently balanced account offers a complex and nuanced portrait of a complex and nuanced individual. 84 min. (JR) Read more

This fascinating personal essay (2003) by Canadian filmmaker Ann Marie Fleming investigates the life of her great-grandfather, the Chinese vaudeville performer Long Tack Sam (1895-1961) — one of the greatest magicians in the world (and one of the key mentors of Orson Welles), who was also an acrobat, though he’s mainly forgotten today. In fact, he circled the globe so many times and experienced so much that recounting his life in many ways means recounting the 20th century. Fleming, an animator and storyteller as well as a documentarian, draws extensively on her own varied talents to approach this elusive topic from many different angles, and her speculations are often as interesting as her findings. Indeed, the way Long Tack Sam keeps sliding out of her and our grasp, even though we wind up feeling that we know him in some fashion, is part of this film’s magic. 90 min. (JR) Read more

In this personal and poetic 2003 video documentary, Babette Mangolte—possibly the best cinematographer now working in experimental cinema (she’s also shot major films by Chantal Akerman, Richard Foreman, Jean-Pierre Gorin, Marcel Hanoun, Sally Potter, Jackie Raynal, Yvonne Rainer, and Michael Snow)—interviews the three leading performers from Robert Bresson’s wondrous 1959 Pickpocket. Bresson wanted to convey directly, without acting, the spiritual essence of individuals, which is why he called his performers interpreters or models. These three were clearly marked by the experience of working for him, and as Mangolte moves from France to Austria to Mexico meeting them she seems as responsive to their self-aware vibrancy and as respectful of their mysteries as Bresson was. 89 min. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 12, 1996). — J.R.

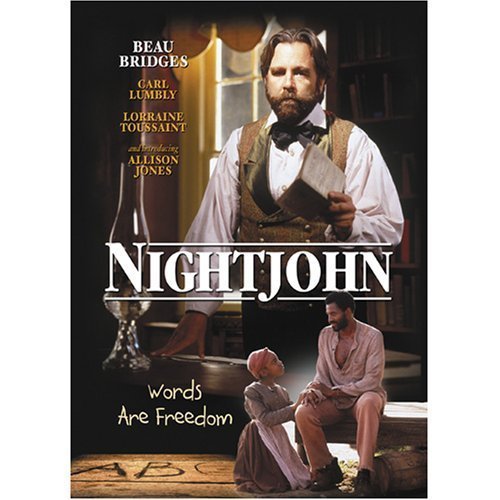

Nightjohn

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Charles Burnett

Written by Bill Cain

With Carl Lumbly, Lorraine Toussaint, Beau Bridges, Allison Jones, Bill Cobbs, Kathleen York, Gabriel Casseus, Tom Nowicki, and Joel Thomas Traywick.

Words are freedom, old man. ‘Cause that’s all that slavery’s made of: words. Laws, deeds, passes: all they are is words. White folks got all the words, and they mean to keep them. You get some words for yourself and you be free. — the character Nightjohn

I think a strong case can be made that Charles Burnett is the most gifted and important black filmmaker this country has ever had. But there’s a fair chance you’ve never heard of him because he isn’t a hustler, he’s never had a mainstream success, and all his work to date has been difficult to pigeonhole. Born in Mississippi in 1943, though raised since infancy in Los Angeles, he was one of several key black filmmakers — including Larry Clark, Julie Dash, Haile Gerima, and Billy Woodbury — to attend UCLA’s graduate film program in the 60s and 70s. His first film to circulate widely, the remarkable 1977 Killer of Sheep, won prizes in 1981 at Berlin and Sundance (before it was known as Sundance) and was one of the first titles selected for the Library of Congress’s Historic Film Registry. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 25, 1991). — J.R.

THE SHELTERING SKY ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Written by Mark Peploe and Bertolucci

With Debra Winger, John Malkovich, Campbell Scott, Jill Bennett, Timothy Spall, Eric Vu-An, and Paul Bowles.

Ever since the 60s the adjective “personal” has been frequently used in relation to commercial movies, and it has almost always been used as an expression of praise. As a reaction to the relatively “impersonal” directorial styles of a Fred Zinnemann, Stanley Kramer, or David Lean, the celebration of the “personal” styles of directors such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, and Alfred Hitchcock ushered in a critical bias that favored the director’s subjective involvement in his or her material — an involvement that is often autobiographical in its implications (such as Ford’s feelings for the Irish and the military, or Hitchcock’s sexual repression and his fear of imprisonment) — over the self-effacement that has often been regarded as both the norm and the ideal of conventional filmmaking.

But in order to argue that the films of supposedly “invisible” stylists like Hawks were highly personal, many auteurists wound up overstating their case, arguing in effect that any director with a discernible “personality” was automatically better than any director without one. Read more

From The Independent: Film and Video Monthly, November 1985 — J.R.

Having attended festivals of many shapes and sizes around the world, I can think of none that is more conducive to the serious viewing of original, offbeat work than the Rotterdam Film Festival. While Rotterdam lacks the global media coverage and accompanying hoopla of a Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Filmex, or Berlin, the festival offers filmmakers a congenial and sympathetic setting. Significantly, American independents as diverse as Jim Jarmusch and Mark Rappaport — as well as European figures like Manoel de Oliveira and Raul Ruiz — made their mark there long before they were treated to New York Film Festival premieres.

A cash prize is awarded each year to a film selected by the Dutch critics. Most recently, it went to Ruiz’s Manoel à l’ïle des merveilles (see two stills above), a French-Portuguese television co-production shot in 16mm, comprising three 50-minute episodes. However, the overall spirit of the festival is anything but competitive, and as a rule the critics prize will go to a film that the critics feel is deserving of special attention rather than an audience favorite. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 24, 1995). — J.R.

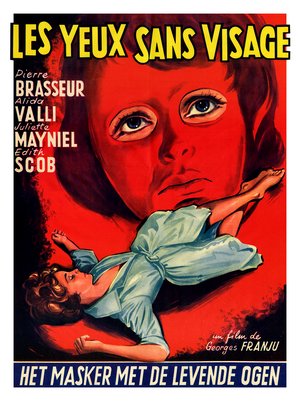

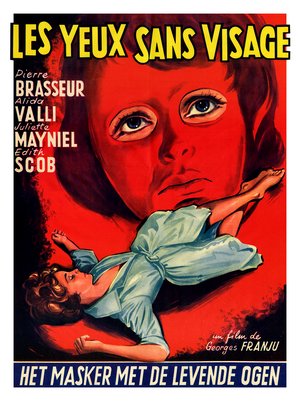

Eyes Without a Face

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Georges Franju

Written by Jean Redon, Pierre Boileau, Thomas Narcejac, Claude Sautet, Pierre Gascar, and Franju

With Edith Scob, Pierre Brasseur, Alida Valli, Juliette Mayniel, Béatrice Altariba, François Guerin, Alexandre Rignault, and Claude Brasseur.

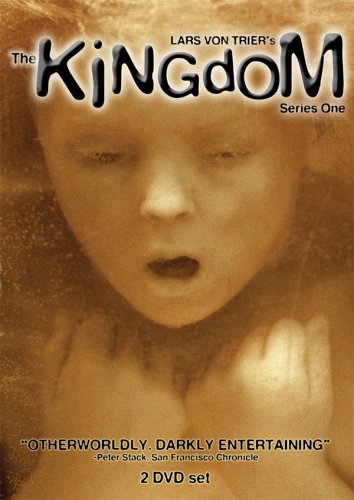

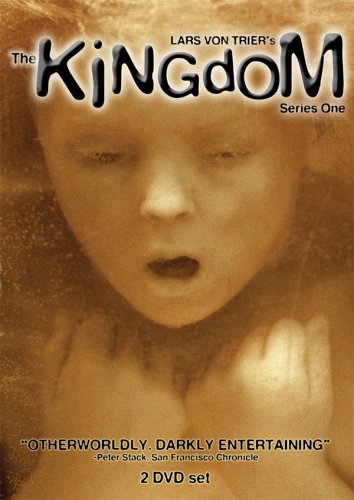

The Kingdom

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Lars von Trier and Morten Arnfred

Written by von Trier, Niels Vorsel, and Tomas Gislason

With Ernst Hugo Jaregard, Kirsten Rolffes, Ghita Norby, Soren Pilmark, Holger Juul Hansen, Annevig Schelde Ebbe, Jens Okking, Otto Brandenburg, Baard Owe, and Birgitte Raabjerg.

They’re both arty European fantasy meditations on the medical profession — that’s about all that Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1959) and Lars von Trier’s The Kingdom (1993) have in common, apart from the fact that they’re both opening here the day after Thanksgiving. The differences between them are much more instructive. Franju’s Les yeux sans visage is a poetic, compact (88 minutes) black-and-white French horror picture about skin grafting that premiered inauspiciously in the United States 32 years ago in a dubbed and reportedly mangled version known as The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus; happily, Facets Multimedia is showing it in its original form and subtitled. Read more

From the January 29, 1988 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

SLEEPWALK

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Sara Driver

Written by Driver and Lorenzo Mans

With Suzanne Fletcher, Ann Magnuson, Dexter Lee, Steven Chen, Tony Todd, Richard Boes, and Ako.

The French term fantastique — which emcompasses science fiction, comic strips, Surrealism, sword and sorcery tales, and many other forms of fantasy — suggests an attitude toward the imagination that is distinctly different from the Anglo-American model. In our more empirical culture, reams of verbiage are devoted to distinguishing science fiction from fantasy, and legislating certain laws of etiquette to govern both — rules of internal consistency and narrative coherence decreeing that all breaches with recognizable reality stem from the same premises, whether these premises be scientific, purely fanciful, or some mixture of the two.

The French tend to be freer and looser about such matters, which helps to explain why such films as Les visiteurs du soir, Picnic on the Grass, Last Year at Marienbad, Je t’aime, je t’aime, Alphaville, Fahrenheit 451, Celine and Julie Go Boating, and Deathwatch pose to English and American temperaments certain problems that are not posed by The Wizard of Oz, Things to Come, It’s a Wonderful Life, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Exorcist, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Blade Runner. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 30, 1996). — J.R.

Foxfire

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Annette Haywood-Carter

Written by Elizabeth White

With Hedy Burress, Angelina Jolie, Jenny Lewis, Jenny Shimizu, Sarah Rosenberg, and Peter Facinelli.

Escape From L.A.

Rating *** A must see

Directed by John Carpenter

Written by Carpenter, Debra Hill, and Kurt Russell

With Russell, Stacy Keach, Steve Buscemi, Peter Fonda, George Corraface, and Cliff Robertson.

Tin Cup

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Ron Shelton

Written by John Norville and Shelton

With Kevin Costner, Rene Russo, Cheech Marin, and Don Johnson.

It’s already pretty clear from reviews and head counts that Escape From L.A. is something of a box-office loser and Tin Cup something of a winner. And although I wrote what follows about Foxfire before I knew its commercial fate, my suspicions were confirmed with such a vengeance that it’s no longer playing in Chicago (keep your eyes peeled for a second run). All three films are worth seeing — at least if you’re willing to settle for something good, not great, during the usual prefall slump — but my preference for Foxfire and Escape From L.A. over Tin Cup isn’t simple contrariness. If you go to movies in the hope of finding something beautiful or imaginative or different, as I do, there’s simply no contest.

Read more

Written for the January/February 2011 Film Comment. — J.R.

Chef-d’oeuvre?

(Luc Moullet, France)

Although ostensibly a short essay inquiring how masterpieces are identified and proclaimed in several art forms (with various apt comparisons and wry asides), this is ultimately a 13-minute defense of the short film itself — the form in which Moullet himself has created the greatest number of masterpieces (and about which he has written often as a critic, most recently in the French magazine Bref). The finale is a presentation of Méliès’ most famous short, Le Voyage dans la lune (1902), with Moullet’s own brilliant audio commentary.—Jonathan Rosenbaum Read more

Written for the Olive Films Blu-Ray in 2016. — J.R.

[Orson Welles’s] desire to transcend the barriers separating the classics, the avant-garde, and popular culture remains, I believe, his most enduring legacy.

— Michael Anderegg, Orson Welles, Shakespeare and Popular Culture (1999)

It seems probable that no American film director ever rattled the American mainstream more than Orson Welles, and none of his features rattled that mainstream more than his two versions of Macbeth, made successively out of the same material he shot in 1947, and released successively in the U.S. in 1948 and 1950. Welles’ fifth completed feature, it was the first of many that would come out in more than one version, and the first that decisively shifted his public status, against his own wishes, from that of commercial studio director to that of arthouse auteur — a profile that would be deviated from only by Touch of Evil a decade later, the only other studio feature he would ever make.

Welles’ approach to the material is wildly neo-primitive and so expressionistic that one can never be entirely sure whether the action is taking place in interiors or exteriors; the same ambiguity persists in the spoken text, where off-screen internal monologue and on-screen external speech often seem only a breath apart. Read more

From the November 4, 1988 issue of the Chicago Reader. This piece is also reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies.

The absence of Rob Tregenza’s three features — Talking to Strangers, The Arc, and Inside/Out— on DVD continues to be a major cultural gap, although he says that does have plans to release them all when he can. (Regarding Inside/Out, here are two more links.) And there’s a fourth feature that he shot more recently in Norway, called Gavagai, which was shown in Chicago at Facets.

Before Godard produced Tregenza’s third feature, Inside/Out, he selected Talking to Strangers as his “critic’s choice” for the Toronto International Film Festival and even wrote an extended review of it for their catalog, the same year that he showed For Ever Mozart; I interviewed him about Histoire(s) du cinema at the same festival after he showed me the three latest episodes in his hotel room. — J.R.

TALKING TO STRANGERS

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Rob Tregenza

With Ken Gruz, Marvin Hunter, Dennis Jordan, Caron Tate, Henry Strozier, Richard Foster, Linda Chambers, and Sarah Rush.

Let us consider this waiter in the cafe. Read more

Commissioned by BFI Video for an April 2015 release. — J.R.

Charlie Chaplin, the late Gilbert Adair liked to assert, doesn’t simply belong to film history; he belongs to history. And the same might be said for Roberto Rossellini’s first major feature, Roma città aperta. Even though it’s routinely regarded as a landmark in film history — the film that decisively put Italian Neorealism on the global map — one could argue that its lasting importance owes far more to the major role it played in humanizing the Italian population for the rest of the world after it emerged from over two decades of Fascist rule under Benito Mussolini.

We don’t hear much about that Fascist rule in Rome Open City, an omission that entails a historical simplification, albeit an understandable as well as an expedient one — not so much an expression of “first things first” as an expression of “second things first,” viewed by most audiences around the world from the vantage point of the war’s end. A project that was first conceived in August 1944, only two months after the Allies had forced the Nazis out of Rome, the film was driven primarily by a desire to expose the brutalities and indignities suffered by Romans under the German occupation as well as the discovery of a common purpose between the Communist and Catholic partisans who had opposed it. Read more

I can’t recall when this was written or what occasioned it (apart from the initial reviews of Eyes Wide Shut when it opened in 1999). — J.R.

Much of the negative critical response to Eyes Wide Shut came from indignant New Yorkers who felt their city had been misrepresented — worst of all, by a native of the Bronx and onetime Manhattan resident who had dared to expatriate himself. “It’s difficult to make a movie about a city you last set foot in 35 years ago,” J. Hoberman wrote in the Village Voice, sidestepping the hypothesis that Kubrick’s last film might be about something else — some elusive, shifting city of the mind, perhaps, as shared by the fearful dreams and imaginations of a married couple. Similarly, Stuart Klawans’ complaint in The Nation that he couldn’t buy “a Village jazz club with a tuxedoed headwaiter and a last set ending at midnight” overlooks the possibility that Kubrick couldn’t either, any more than he could believe in an intersection in that same Village of Miller and Wren — two nonexistent streets even when he lived in the city.

The film is full of such “off” details, and not simply because all of it was shot in an English studio. Read more

From the Chicago Reader, January 10, 1992. — J.R.

THE FILMS OF MIKE LEIGH

Among the buzzwords Marshall McLuhan coined in the 60s, “global village” has always seemed one of the more dubious. The naive notion that TV brings the whole world to our doorsteps — and presumably our doorsteps to the rest of the world — seems founded on assumptions that don’t bear close scrutiny. What do we mean by “the world,” for instance? And what do we mean by TV? TV may afford us some touristic glimpses of elsewhere, along with all the usual ideological baggage of the tourist, but when it comes to closer and better understandings of foreign cultures, I suspect TV may do more harm than good by fostering complacent illusions of knowledge: images wrapped in tidy American sound bites for easy consumption, postage-stamp peeks into worlds often defined in part by what we still don’t know.

What TV seldom offers us — unless we understand other languages and possess satellite dishes — is the rare privilege of overhearing other cultures talk to themselves, experiencing them from within rather than on our terms. To be on the inside looking out offers a different kind of knowledge, attained more by osmosis and intuition than by simplification, translation, or exegesis. Read more