Half-Caste Agit-Prop [THE CHANT OF JIMMIE BLACKSMITH]

From The Soho News (September 3, 1980). –- J.R.

The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith

Written and directed by Fred Schepisi

Based on the novel by Thomas Keneally

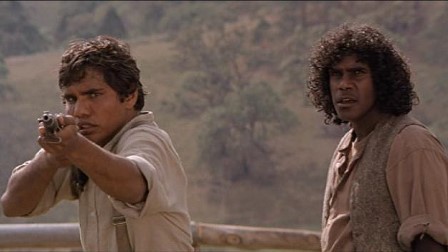

For a good 80 percent or so of its running time, the experience

of seeing The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith affords a

salutary, beautiful shock. Films that are even halfway honest

about racism — Mandingo and Richard Pryor Live in

Concert are the most recent examples that spring to mind

— are so unexpected that they’re often accused of being racist

themselves, perhaps because of the deeply rooted taboos that

they expose and violate.

There’s no question that Fred Schepisi’s powerhouse Australian

movie — adapted from a novel by Thomas Keneally (who plays a

small but significant role as a lecherous cook), and “based on real

events that took place in Australia at the turn of the century”

(just before the federation of Australian colonies) – is agit-prop,

ideologically slanted. But then again, it’s hard to think of any

other current release — including, say, The Empire Strikes

Back and Dressed to Kill -– that isn’t.

The aforementioned hits perform in part the not-so-innocent

task of turning contemporary objects of confusion and disgust

(recent architecture and sex, respectively) into occasions for

exhilarated lyricism. Read more