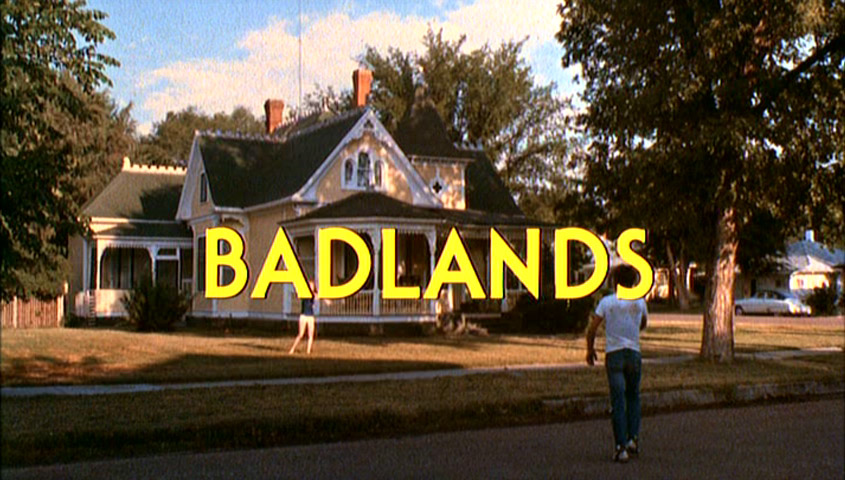

Here are my reviews of two Malick films that I like much more than The Tree of Life, written almost a quarter of a century apart.

First, my review of Badlands from the November 1974 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin:

U.S.A., 1973

Director: Terrence Malick

It would hardly be an exaggeration to call the first half of Badlands a revelation -– one of the best literate examples of narrated American cinema since the early days of Welles and Polonsky. Compositions, actors, and lines interlock and click into place with irreducible economy and unerring precision, carrying us along before we have time to catch our breaths. It is probably not accidental than an early camera set-up of Kit on his garbage route recalls the framing of a neighborhood street that introduced us to the social world of Rebel Without a Cause: the doomed romanticism courted by Kit and dispassionately recounted by Holly immediately evokes the Fifties world of Nicholas Ray -– and more particularly, certain Ray-influenced (and narrated) works of Godard, like Pierrot le fou and Bande à part. Terrence Malick’s eye, narrative sense, and handling of affectless violence are all recognizably Godardian, but they flourish in a context more easily identified with Ray. Read more

I haven’t much cared for any of the Gaspar Noé films I’ve seen so far except for I Stand Alone, but I persist in finding this one a corrosive masterpiece. This review appeared in the July 9, 1999 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

I Stand Alone

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Gaspar Noe

With Philippe Nahon, Blandine Lenoir, Frankye Pain, Martine Audrain, and Roland Gueridon.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Gaspar Noé’s first full-length feature is a genuine shocker. It’s a sequel to his 40-minute Carne, a film that didn’t do much for me when it played the film-festival circuit in the early 90s, though I wouldn’t mind seeing it again now. This feature is called Seul contre tous, which translates literally as “alone against everybody”; I Stand Alone is cornier but rolls more easily off the tongue.

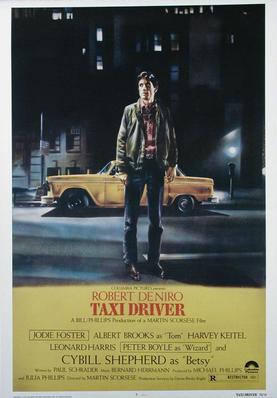

You don’t need to know anything about Carne to follow or appreciate I Stand Alone — which thoughtfully provides a precis of Carne in its opening minutes — but some familiarity with Taxi Driver or any of its spin-offs might help you experience its full wallop. Like Martin Scorsese’s film, I Stand Alone centers on an armed and enraged loner who spews macho, racist, and homophobic bile — most of which he mutters to himself –a nd is ready to mow down everyone in sight. Read more

Here are ten of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007). — J.R.

Scene

1990 / Close Up – The motorcycle ride of Makhmalbaf and Sabzian.

Iran. Director: Abbas Kiarostami. Cast: Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Hossein Sabzian. Original title: Nema-ye Nazdi.

Why It’s Key: A convicted imposter finally meets the man he’s been impersonating, and they set off together to visit the family that was fooled.

Hossein Babzian, a bookbinder, emerges from a jail sentence for having impersonated famous filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf in order to ingratiate himself with the well-to-do Ahankhah family, pretending he was planning a movie about them. He’s greeted by the real Makhmalbaf, arriving on his motorbike to take him to visit the Ahankhahs, and filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami and his crew, who have arranged this meeting, are filming the entire encounter from a distance. We hear them saying that Makhmalbaf’s lapel mike is faulty, and notice that the dialogue between Makhmalbaf and Sabzian (“Do you prefer being Makhmalbaf or being Sabzian? I’m tired of being me”) periodically becomes inaudible — on the street, after Sabzian climbson the back of the motorbike, and when they stop briefly for Sabzian to buy flowers for the Ahankhans. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1992). — J.R.

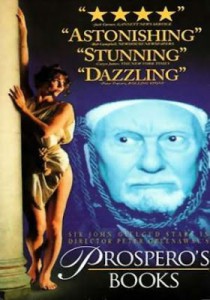

Poor John Gielgud tried for years to set up a film version of The Tempest that would record his performance of Prospero; he finally had to settle for director Peter Greenaway. Gone is any sense of drama or character; the cluttered spectacle yields no overriding design but simply disconnected MTV-like conceits or mini-ideas every three seconds. Don’t expect to enjoy Shakespeare’s poetry: aural distractions constantly intrude, from sound effects, echo chambers, and Michael Nyman’s neoclassical Muzak. And don’t expect to enjoy Sacha Vierny’s exquisitely lit cinematography: double exposures, ugly rectangular overlays, graceless quick cutting, and lots of nude or semiclad extras cavorting in clunky modernist choreography drain all the pleasure from that as well. On the other hand, if you share Greenaway’s misanthropy, you might get some kicks out of watching a cherub piss on everyone in sight. With Michael Clark, Michel Blanc, Erland Josephson, and Isabelle Pasco (1991). R, 124 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Commisssioned by the bilingual, semi-annual Spanish journal Found Footage Magazine for their second issue, published in April 2016.

One good reason for reposting this essay is that Thom Andersen has pointed out a few errors. I’ve added his comments as a postscript. — J.R.

The rapidly and constantly expanding proliferation of films and videos about cinema is altering some of our notions about film history in at least two significant ways. For one thing, now that it has become impossible for any individual to keep abreast of all this work, our methodologies for assessing it as a whole have to be expanded and further developed. And secondly, insofar as one way of defining work in cinematic form and style that is truly groundbreaking is to single out work that defines new areas of content, the search for such work is one of the methodologies that might be most useful. In my case, this is a search that has led to considerations of two recent videos, Mark Rappaport’s 33-minute I, Dalio—or The Rules of the Game (2014) and Thom Andersen’s 108-minute The Thoughts That Once We Had (2015). Both are highly personal works that also define relatively new areas of on-film film analysis, forms of classification that can be described here as indexing (in this case, indexing and commenting on the career of a French character actor, Marcel Dalio) and taxonomy (in this case, illustrating portions of a taxonomy offered by a French writer, Gilles Deleuze, as applied to a partial and idiosyncratic yet fairly comprehensive history of cinema). Read more

From the December 31, 1989 Chicago Reader.

Shortly before his third marriage Caveh Zahedi recounts and restages events from his life showing how his addiction to prostitutes doomed his first two. This deconstructive, minimalist comedy, like his 1990 A Little Stiff (codirected by Greg Watkins) and 1994 I Don’t Hate Las Vegas Anymore, re-creates events with the vain self-deprecation of one of his role models, Woody Allen. Here he adds critical commentary, animation, and playful asides about the perils and vicissitudes of low-budget filmmaking, and his offbeat intelligence and low-burning wit recall his inspired rap on film theory in Waking Life. 90 min. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 23, 2007). — J.R.

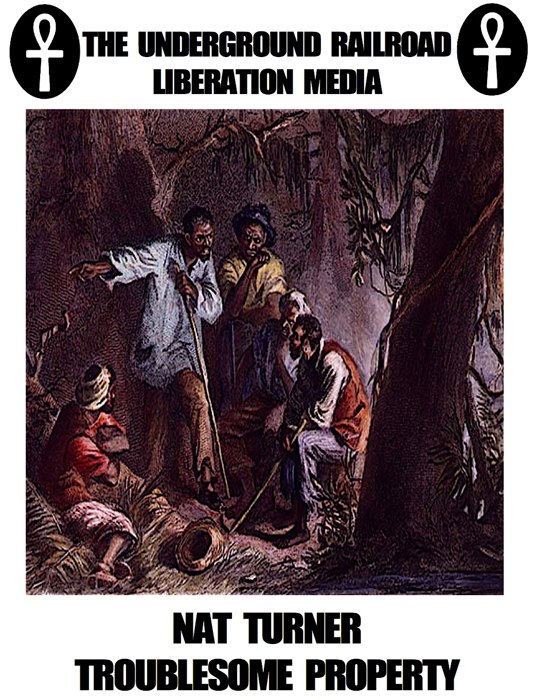

NAT TURNER: A TROUBLESOME PROPERTY ****

DIRECTED BY CHARLES BURNETT | WRITTEN BY BURNETT, FRANK CHRISTOPHER, AND KENNETH S. GREENBERG

WITH CARL LUMBLY, TOM NOWICKI, TOMMY HICKS, JAMES OPHER, WILLIAM STYRON, ERIC FONER, MARY KEMP DAVIS, OSSIE DAVIS, EKEWUEME MICHAEL THELWELL, AND BURNETT

THE ASTRONAUT FARMER *

DIRECTED BY MICHAEL POLISH | WRITTEN BY MARK AND MICHAEL POLISH

WITH BILLY BOB THORNTON, VIRGINIA MADSEN, BRUCE DERN, MAX THIERIOT, TIM BLAKE NELSON, BRUCE WILLIS, KIERSTEN WARREN, AND RICHARD EDSON

Very little is known about Nat Turner, the black slave in Virginia’s Southampton County who led a revolt by more than 50 other black slaves in August 1831. Over two days they slaughtered 57 white men, women, and children, and after the rebellion was suppressed, 60 to 80 slaves were summarily executed and mutilated. As one historian notes in Charles Burnett’s hour-long TV documentary, Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property (2003), screening Sunday at the DuSable Museum of African American History, we have precise information about Turner’s victims but know almost nothing about the slaughtered blacks.

Most of what’s known about Turner is based on his unverifiable “confession” to a white lawyer, Thomas Gray, before he was executed. Read more

From the July 1, 1994 Chicago Reader.

Robert Zemeckis, combining his taste for brittle comedy (Used Cars), mutilated bodies (Death Becomes Her), and recycled history (Back to the Future and Who Framed Roger Rabbit), won an Oscar for this tear-jerking 1994 comedy about a slow-witted southerner (Tom Hanks) living through an absurdist half century of American great events. Zemeckis banks on the innocence of two parties, Gump and the spectator, homogenizing culture and politics into a safe, sweet, palatable nugget. Judging by the the movie’s enduring popularity, the message that stupidity is redemption is clearly what a lot of Americans want to hear. With Robin Wright, Gary Sinise, Mykelti Williamson, and Sally Field; Eric Roth and Zemeckis adapted a novel by Winston Groom. PG-13, 142 min. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 10, 2003). — J.R.

Spike Lee’s best feature since Do the Right Thing. Though none of the major characters is black, it’s one of Lee’s most personal and deeply felt works, and the fact that it’s based on someone else’s material — David Benioff’s adaptation of his novel — makes the film all the more impressive. The narrative follows a former drug dealer (Edward Norton) spending his last 24 hours in Manhattan before beginning a seven-year prison term, though it’s also very much about the people closest to him: his girlfriend (Rosario Dawson), two best friends (Barry Pepper and Philip Seymour Hoffman), and father (Brian Cox). The film persuades us to think long and hard about what prison means, and Lee has shaped it like a poem that builds into an epic lament, especially in a beautiful and tragic closing that risks absurdity to achieve the sublime. With Anna Paquin. 134 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the March 1, 1996 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

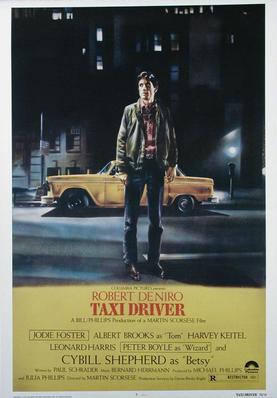

Taxi Driver

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Paul Schrader

With Robert De Niro, Jodie Foster, Harvey Keitel, Cybill Shepherd, Albert Brooks, Peter Boyle, Leonard Harris, Steven Prince, and Martin Scorsese.

Perhaps the most formally ravishing — as well as the most morally and ideologically problematic — film ever directed by Martin Scorsese, the 1976 Taxi Driver remains a disturbing landmark for the kind of voluptuous doublethink it helped ratify and extend in American movies. Of all Scorsese’s movies, Taxi Driver — being screened this week at the Music Box in a 20th-anniversary “restoration” that’s in stereo for the first time — is for me the most seductive, though I wouldn’t call it either his best film (I’d choose the underrated The King of Comedy) or his most gut-wrenching (I’d pick the overrated Raging Bull). Most of the glamorous depictions of hell on earth and odes to stoical despair about a postapocalyptic civilization found in monuments to capitalist-urban squalor, including Blade Runner and Seven, can be traced back to Taxi Driver, and if it continues to exert an enormous claim on our imagination, this is surely because we continue to live in its vengeful, puritanical fantasies — as well as with the dire consequences of those fantasies. Read more

HEAVEN’S MY DESTINATION by Thornton Wilder (New York: Harper Perennial), 2003, 240 pp.

In fact, the copy that I’ve just reread with pleasure for the second time is a first edition (New York/London: Harper & Brothers, 1935). But Wilder as a novelist is so unfashionable that there’s nothing very pricey about this book in any shape or form. I persist in regarding Heaven’s My Destination as one of the truly great American novels, and I’ve pretty much felt this way ever since I first encountered it in the 1960s — and not just an archetypal middle-American road farce with memorable period settings (including trains, cars, hotels, campsites, boarding houses, bordellos, restaurants, and movie theaters) but also the potential basis for a great movie. It concerns a 23-year-old textbook salesman and devout Baptist from Michigan named George Brush, moving through Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, and Arkansas during the height of the Depression, spreading havoc and consternation wherever he goes with his hilarious and maddening fanaticism. (A key line towards the end: “`Isn’t the principle of a thing more important than the people that live under the principle?'”)

I can’t really fathom why this incredible mini-epic has never been canonized — shunned by the Library of America, ignored by Alfred Kazin. Read more

An “En movimiento” column for Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. This is the original, longer version, before I had to trim it down to suit the magazine’s new design and format — J.R.

It’s logical and inevitable that the meanings of films change over time. After all, we’re the ones who determine, discover, and/or describe those meanings, and it’s obvious that we and our understandings change over time. At some point during my first decade, I saw a film in which poisoned biscuits played some role in the plot, and during a trip with my parents soon afterwards, I refused to eat biscuits in a hotel restaurant. I’ve subsequently been unable to remember or otherwise pinpoint the title of this film, even after several Google searches, but I’m sure that if I could resee it today, I wouldn’t take it as a practical warning about consuming biscuits.

I’ve had better luck in finding and revisiting another film that upset me during my early childhood. A protracted search in this case eventually yielded The Unfinished Dance (Henry Koster, 1947), which I most likely saw at a revival in my hometown in Alabama circa 1949 or 1950, when I was six or seven, and didn’t see again until over six decades later, after ordering a DVD. Read more

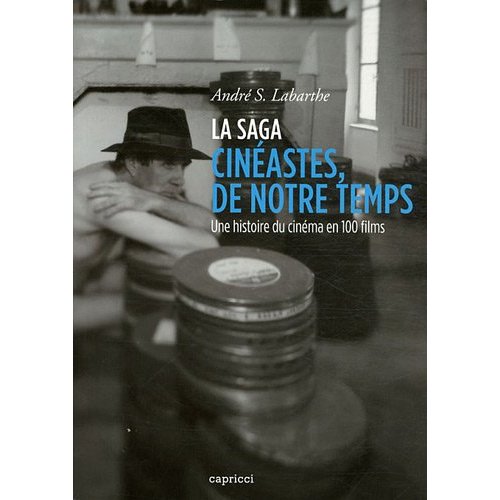

Some of the most successful and fruitful ongoing enterprises related to film history have been either ignored or taken for granted (which sometimes amounts to the same thing) due to their omnipresence. In book publishing, the two most outstanding examples that come to mind are, in France, the series of monographs devoted to film directors issued by Seghers(which finally expired many years ago, I believe in the 70s or 80s) and, in the U.K., the BFI Classics and BFI Modern Classics, launched in 1992 and, to be the best of my knowledge, still going strong.

Considerably more formidable is the series of 80-odd French television documentaries about filmmakers produced by Janine Bazin (the widow of André Bazin) and André S. Labarthe, initially called Cinéastes de notre temps when it was produced by the ORTF between 1964 and 1972, and revived as Cinéma, de notre temps when it was produced by Arte between 1990 and 2003, the year that Janine Bazin died, and then taken up again by Cinécinéma in 2006. Some of the more interesting of the earlier documentaries were remarkable in the various ways that they stylistically imitated their subjects, as in the programs on Cassavetes, Samuel Fuller, and Josef von Sternberg. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 12, 1993).

A fascinating and highly entertaining hour-long video (1992) by Dan Bessie about a trio of puppeteers12 who toured America for more than seven decades with their satirical musical revues: Bessie’s 92-year-old uncle, puppeteer Harry Burnett; Burnett’s cousin Forman Brown; and Brown’s lover, Roddy Brandon. (Their LA theater–which counted Charlie Chaplin and Albert Einstein among its fans–was called the Turnabout because it had a puppet stage at one end, a cabaret stage at the other, and seats that swiveled.) Burnett and Brown, both still alive, perform entertainingly, and we also get fascinating archival footage of some of their shows. Brown, who wrote songs, also talks about his recently republished 1934 novel Better Angel, originally published under a pseudonym, perhaps the only gay novel of its period with a happy ending. A fascinating piece of show-business history, this also offers many interesting comments about what it meant to be gay in the early part of this century. On the same Gay & Lesbian Film Festival program, four short films by Sandi DuBowski, Ruth Scovill, and Iara Lee; one of Lee’s films features Allen Ginsberg narrating, the other features Matt Dillon reading T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Read more

From the August 29, 2003 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

The Virgin Suicides (2000) revealed writer-director Sofia Coppola to be a genuine original, and now that she’s working with her own material the freshness of her vision is even more apparent. This second feature traces the brief romantic friendship between a jaded movie star and family man (Bill Murray), who’s in Tokyo shooting a whiskey commercial, and a bored young newlywed less than half his age (Scarlett Johansson), who’s waiting for her photographer husband (Giovanni Ribisi) to return from a trip. Coppola does a fair job of capturing the fish-tank ambience of nocturnal, upscale Tokyo and showing how it feels to be a stranger in that world, and an excellent job of getting the most from her lead actors. Unfortunately, I’m not sure she accomplishes anything else. R, 105 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more