Monthly Archives: July 2022

True Grit [ROSETTA]

From the Chicago Reader (January 14, 2000); also reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema. — J.R.

Rosetta

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne

With Emilie Dequenne, Fabrizio Rongione, Anne Yernaux, Olivier Gourmet, and Bernard Marbaix.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

I saw Rosetta three weeks ago, and haven’t recovered from it since. In fact, I didn’t see any film since the Dardennes’, except films for work. It moves me to the heart of my heart, this film about the necessity of life, the impossibility of morality, the soil of human experience. [A teaching colleague] told me that he couldn’t watch it because he thought too much about [Robert Bresson’s] Mouchette, but precisely, it’s at last Mouchette today, our Mouchette, the one we deserve, without any heaven and any transcendence. Her scream, ‘Mama! Y’a d’la boue! Y’a d’la boue!’ [‘Mama! It’s full of mud! It’s full of mud!’] haunts me, I can’t forget it, it’s exactly the despair of being in life without any pathos, any margin, just real life in the immediacy of the impulse. — E-mail from film critic Nicole Brenez

The 80s practically ended with the euphoric takeover of Tiananmen Square by more than a million demonstrators led by students, many with access to fax machines, though a brutal government crackdown followed. Read more

Ethereal Girl [WHO’S THAT GIRL]

This was the first long review I wrote for the Chicago Reader after I started working there, but its publication was delayed for almost a couple of months until October 30, 1987 because the film was pulled from distribution just before we were going to press. — J.R.

WHO’S THAT GIRL

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by James Foley

With Madonna, Griffin Dunne, Haviland Morris, John McMartin, and John Mills.

The current spate of recycled movies is only the latest stage in a process that has been in force for almost three decades, ever since the French New Wave launched the idea of a self-devouring cinema. Broadly speaking, the movement started out as esoteric polemical criticism (in print and on-screen) in the 60s, gravitated toward name-dropping and flag-waving testimonials in the 70s, and has finally degenerated in the 80s to an insidious kind of self-censorship that uses the past — and a severely delimited version of it at that — as a kind of stopper to prevent too much of the present from leaking through.

It’s a cynical truism of journalism that any story with 100 percent new information is virtually unusable. In order to provide the reader or spectator with a safety net, most of the story has to be based on old information, even if much of that old news turns out to be out of date or false. Read more

Masumura’s Madness + sidebar (Among the Missing: 10 Key Masumura Features)

This was written for Film Comment in 2002, but only the first part was published in their September-October issue that year, under the title “Enlightened Madness”. This was designed to be accompanied by a sidebar highlighting ten of Masumura’s films, but the editor, Gavin Smith, after proposing the sidebar and thereby getting me to revise the first piece accordingly, subsequently decided to place the sidebar only on the magazine’s website, thereby sabotaging my plan for the two pieces to work together, as a two-part unit, and reducing much of the sidebar, as a stand-alone unit, to gibberish.

Much of both parts got recycled years later in an essay included in Movie Mutations, a collection I coedited with Adrian Martin. — J.R.

To appropriate one of the categories of Andrew Sarris’s The American Cinema, Yasuzo Masumura (1924-1986) is a “subject for further research.” Considering that he made 58 films between 1957 and 1982, none of which has ever had a normal commercial run in this country, that may even be putting it mildly. But so far I’ve managed to see 38, all but one over the past four years, and though the range in quality is enormous, I’d swear by at least half of them. Read more

Sade, Resnais, Lubitsch, MGM

The following is a text commissioned by film critic and scholar Francois Thomas for an ongoing online series, “Les Papiers Alain Resnais,” devoted to items in the Alain Resnais archives and individual commentaries about them (https://www.imec-archives.com/matieres-premieres/papiers/alain-resnais). Rather than post my original English text, which Thomas translated into French, and which appeared on the site in French and English last week, I’ve slightly revised the web site’s English translation of his French text to make it both more idiomatic and closer to what I had in mind. And I begin with his “hasty” English translation (with explanatory glosses in brackets) of Resnais’ letter, which he did for me, reproduced here in bold. (Francois told me that Resnais hated to write letters and wrote very few of them; this one was mostly typewritten.)

Letter from Alain Resnais to Richard Seaver on the Délivrez-nous du bien project , October 20, 1970:

Dear Dick,

Your letter of October 10 from Southampton [New York] arrived last night. Probably intersected with the one I sent on the 8th, containing answers to several questions you asked me. But — is it a feeling — you don’t seem to be aware of the one I sent you on September 9 (and I remember that you didn’t seem to have received one of the notes I sent from London at the end of July either).

True Romances [HAV PLENTY & MR. JEALOUSY]

From the Chicago Reader (June 19, 1998). — J.R.

Hav Plenty

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Christopher Scott Cherot

With Chenoa Maxwell, Cherot, Tammi Catherine Jones, Robinne Lee, and Reginald James.

Mr. Jealousy

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Noah Baumbach

With Eric Stoltz, Annabella Sciorra, Chris Eigeman, Carlos Jacott, Marianne Jean-Baptiste, Brian Kerwin, Peter Bogdanovich, and Bridget Fonda.

Two eclectic, youthful, and surprisingly upbeat romantic comedies open this week, both by writer-directors; both about blocked novelists, relationships, fear of commitment, jealousy, self-torturing neurosis, betrayal, and ultimate fulfillment; and both set in upscale, urban east-coast milieus. I had a good time at Christopher Scott Cherot’s Hav Plenty and Noah Baumbach’s Mr. Jealousy both times I saw them, though I couldn’t believe in either all the way through, and neither made me laugh out loud very often. Presented as hand-crafted self-portraits that have agreed to play by certain commercial rules and genre conventions, both teem with eccentric tics and personal energies, giving us the pleasure of contact with an individual intelligence — something that seldom happens with bigger-budget fare.

The eccentric tics in Hav Plenty begin with the title — which conflates the first name of heroine Havilland Savage (Chenoa Maxwell) and the last name of hero Lee Plenty (Cherot) — and include Philippians 4:12 (“I know what it is to be in need, and I know what it is to have plenty. Read more

Wrinkles in Time [ALONE. LIFE WASTES ANDY HARDY]

From the February 18, 2000 Chicago Reader. This piece is reprinted in my Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia.— J.R.

Alone. Life Wastes Andy Hardy

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Martin Arnold

With Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland, and Fay Holden.

Wearing suspenders, Mickey Rooney as Andy Hardy steps behind his mother (Fay Holden), clutching her left shoulder and right forearm with his two hands, and firmly kisses the back of her neck while she slowly nods her head with a stoic, worldly-wise expression. In a series of stuttering, staccato jerks, he does the same thing again, to the throbbing strains of eerie, ghostly music. Then he does it a third time, pausing first to rock back and forth from one foot to another a good many times, as if he had ants in his pants. When he kisses the back of his mom’s neck this time, his lips seem to remain glued there. This embrace, his barely perceptible jaw movements, and her steadily bobbing head all conspire to suggest something vaguely obscene and depraved. Could Andy have become some kind of Dracula, sucking blood from his mother’s neck? Or do the slow pumping rhythm and repeated nervous thrusts represent some kind of sexual motion? Read more

Reviews of Two Terrence Malick Films

Here are my reviews of two Malick films that I like much more than The Tree of Life, written almost a quarter of a century apart.

First, my review of Badlands from the November 1974 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin:

U.S.A., 1973

Director: Terrence Malick

It would hardly be an exaggeration to call the first half of Badlands a revelation -– one of the best literate examples of narrated American cinema since the early days of Welles and Polonsky. Compositions, actors, and lines interlock and click into place with irreducible economy and unerring precision, carrying us along before we have time to catch our breaths. It is probably not accidental than an early camera set-up of Kit on his garbage route recalls the framing of a neighborhood street that introduced us to the social world of Rebel Without a Cause: the doomed romanticism courted by Kit and dispassionately recounted by Holly immediately evokes the Fifties world of Nicholas Ray -– and more particularly, certain Ray-influenced (and narrated) works of Godard, like Pierrot le fou and Bande à part. Terrence Malick’s eye, narrative sense, and handling of affectless violence are all recognizably Godardian, but they flourish in a context more easily identified with Ray. Read more

The Brutal Truth (on I STAND ALONE)

I haven’t much cared for any of the Gaspar Noé films I’ve seen so far except for I Stand Alone, but I persist in finding this one a corrosive masterpiece. This review appeared in the July 9, 1999 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

I Stand Alone

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Gaspar Noe

With Philippe Nahon, Blandine Lenoir, Frankye Pain, Martine Audrain, and Roland Gueridon.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Gaspar Noé’s first full-length feature is a genuine shocker. It’s a sequel to his 40-minute Carne, a film that didn’t do much for me when it played the film-festival circuit in the early 90s, though I wouldn’t mind seeing it again now. This feature is called Seul contre tous, which translates literally as “alone against everybody”; I Stand Alone is cornier but rolls more easily off the tongue.

You don’t need to know anything about Carne to follow or appreciate I Stand Alone — which thoughtfully provides a precis of Carne in its opening minutes — but some familiarity with Taxi Driver or any of its spin-offs might help you experience its full wallop. Like Martin Scorsese’s film, I Stand Alone centers on an armed and enraged loner who spews macho, racist, and homophobic bile — most of which he mutters to himself –a nd is ready to mow down everyone in sight. Read more

10 Key Moments in Films (4th Batch)

Here are ten of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007). — J.R.

Scene

1990 / Close Up – The motorcycle ride of Makhmalbaf and Sabzian.

Iran. Director: Abbas Kiarostami. Cast: Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Hossein Sabzian. Original title: Nema-ye Nazdi.

Why It’s Key: A convicted imposter finally meets the man he’s been impersonating, and they set off together to visit the family that was fooled.

Hossein Babzian, a bookbinder, emerges from a jail sentence for having impersonated famous filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf in order to ingratiate himself with the well-to-do Ahankhah family, pretending he was planning a movie about them. He’s greeted by the real Makhmalbaf, arriving on his motorbike to take him to visit the Ahankhahs, and filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami and his crew, who have arranged this meeting, are filming the entire encounter from a distance. We hear them saying that Makhmalbaf’s lapel mike is faulty, and notice that the dialogue between Makhmalbaf and Sabzian (“Do you prefer being Makhmalbaf or being Sabzian? I’m tired of being me”) periodically becomes inaudible — on the street, after Sabzian climbson the back of the motorbike, and when they stop briefly for Sabzian to buy flowers for the Ahankhans. Read more

Prospero’s Books

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1992). — J.R.

Poor John Gielgud tried for years to set up a film version of The Tempest that would record his performance of Prospero; he finally had to settle for director Peter Greenaway. Gone is any sense of drama or character; the cluttered spectacle yields no overriding design but simply disconnected MTV-like conceits or mini-ideas every three seconds. Don’t expect to enjoy Shakespeare’s poetry: aural distractions constantly intrude, from sound effects, echo chambers, and Michael Nyman’s neoclassical Muzak. And don’t expect to enjoy Sacha Vierny’s exquisitely lit cinematography: double exposures, ugly rectangular overlays, graceless quick cutting, and lots of nude or semiclad extras cavorting in clunky modernist choreography drain all the pleasure from that as well. On the other hand, if you share Greenaway’s misanthropy, you might get some kicks out of watching a cherub piss on everyone in sight. With Michael Clark, Michel Blanc, Erland Josephson, and Isabelle Pasco (1991). R, 124 min. (JR)

I Am A Sex Addict

From the December 31, 1989 Chicago Reader.

Shortly before his third marriage Caveh Zahedi recounts and restages events from his life showing how his addiction to prostitutes doomed his first two. This deconstructive, minimalist comedy, like his 1990 A Little Stiff (codirected by Greg Watkins) and 1994 I Don’t Hate Las Vegas Anymore, re-creates events with the vain self-deprecation of one of his role models, Woody Allen. Here he adds critical commentary, animation, and playful asides about the perils and vicissitudes of low-budget filmmaking, and his offbeat intelligence and low-burning wit recall his inspired rap on film theory in Waking Life. 90 min. (JR) Read more

Beautifully Fake and Just Plain Phony

From the Chicago Reader (February 23, 2007). — J.R.

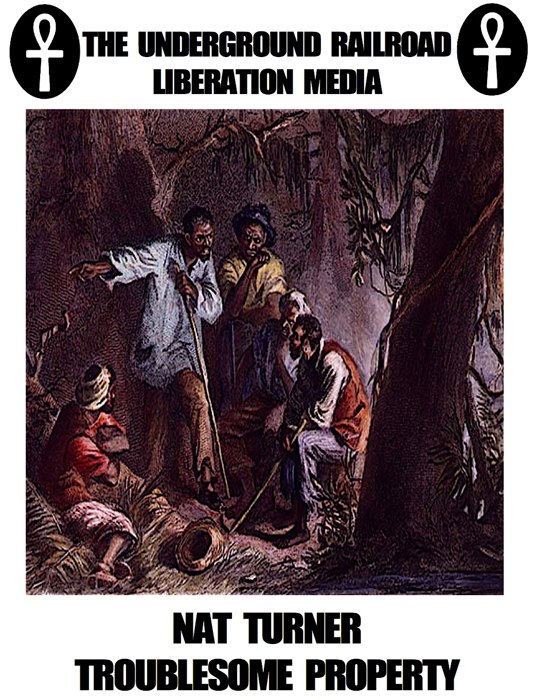

NAT TURNER: A TROUBLESOME PROPERTY ****

DIRECTED BY CHARLES BURNETT | WRITTEN BY BURNETT, FRANK CHRISTOPHER, AND KENNETH S. GREENBERG

WITH CARL LUMBLY, TOM NOWICKI, TOMMY HICKS, JAMES OPHER, WILLIAM STYRON, ERIC FONER, MARY KEMP DAVIS, OSSIE DAVIS, EKEWUEME MICHAEL THELWELL, AND BURNETT

THE ASTRONAUT FARMER *

DIRECTED BY MICHAEL POLISH | WRITTEN BY MARK AND MICHAEL POLISH

WITH BILLY BOB THORNTON, VIRGINIA MADSEN, BRUCE DERN, MAX THIERIOT, TIM BLAKE NELSON, BRUCE WILLIS, KIERSTEN WARREN, AND RICHARD EDSON

Very little is known about Nat Turner, the black slave in Virginia’s Southampton County who led a revolt by more than 50 other black slaves in August 1831. Over two days they slaughtered 57 white men, women, and children, and after the rebellion was suppressed, 60 to 80 slaves were summarily executed and mutilated. As one historian notes in Charles Burnett’s hour-long TV documentary, Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property (2003), screening Sunday at the DuSable Museum of African American History, we have precise information about Turner’s victims but know almost nothing about the slaughtered blacks.

Most of what’s known about Turner is based on his unverifiable “confession” to a white lawyer, Thomas Gray, before he was executed. Read more

Forrest Gump

From the July 1, 1994 Chicago Reader.

Robert Zemeckis, combining his taste for brittle comedy (Used Cars), mutilated bodies (Death Becomes Her), and recycled history (Back to the Future and Who Framed Roger Rabbit), won an Oscar for this tear-jerking 1994 comedy about a slow-witted southerner (Tom Hanks) living through an absurdist half century of American great events. Zemeckis banks on the innocence of two parties, Gump and the spectator, homogenizing culture and politics into a safe, sweet, palatable nugget. Judging by the the movie’s enduring popularity, the message that stupidity is redemption is clearly what a lot of Americans want to hear. With Robin Wright, Gary Sinise, Mykelti Williamson, and Sally Field; Eric Roth and Zemeckis adapted a novel by Winston Groom. PG-13, 142 min. (JR) Read more

25th Hour

From the Chicago Reader (January 10, 2003). — J.R.

Spike Lee’s best feature since Do the Right Thing. Though none of the major characters is black, it’s one of Lee’s most personal and deeply felt works, and the fact that it’s based on someone else’s material — David Benioff’s adaptation of his novel — makes the film all the more impressive. The narrative follows a former drug dealer (Edward Norton) spending his last 24 hours in Manhattan before beginning a seven-year prison term, though it’s also very much about the people closest to him: his girlfriend (Rosario Dawson), two best friends (Barry Pepper and Philip Seymour Hoffman), and father (Brian Cox). The film persuades us to think long and hard about what prison means, and Lee has shaped it like a poem that builds into an epic lament, especially in a beautiful and tragic closing that risks absurdity to achieve the sublime. With Anna Paquin. 134 min. (JR)