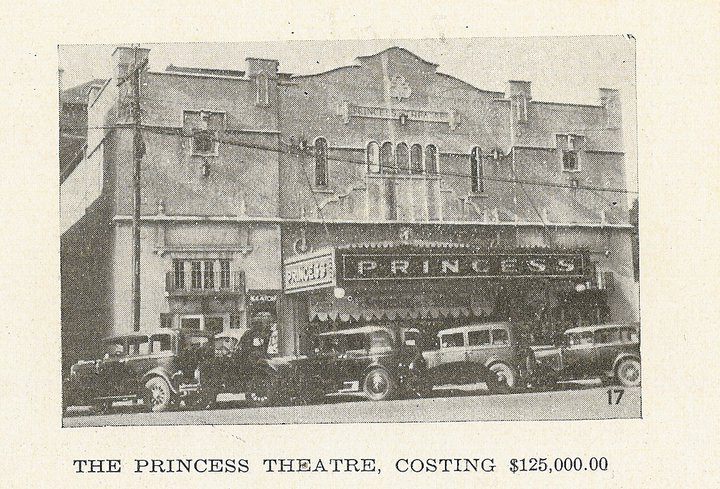

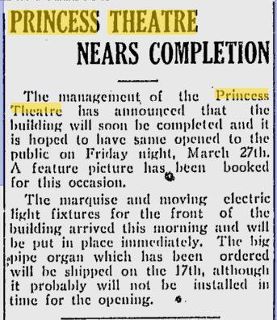

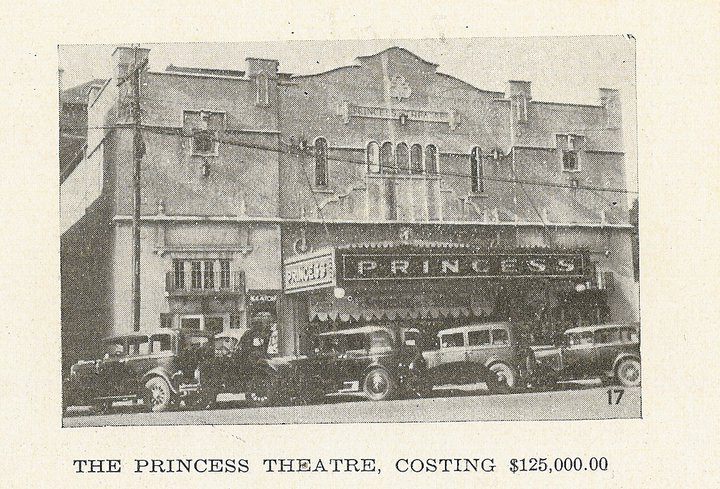

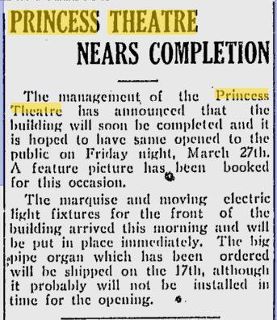

I’m terrible when it comes to dating cars from any period, especially during the early part of the 20th century. According to my memoir Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), which I researched pretty thoroughly back in the late 1970s, “The Florence Princess, an $85,000 Opera House, [opened] triumphantly on Labor Day, September 1, 1919” (see pp. 180-181 in the book for more details). But according to this newspaper photo — which I don’t recall ever having seen before, posted by Betty Terry on “Remembering Florence” (a Facebook page) last November — it cost $40,000 more than that; and according to a news clipping that went with it (see below), which she posted about a week later, it opened, apparently in some other form, in 1925. An abiding mystery…but of course we can never get very far by believing what’s printed in newspapers, then or now, even when that’s all we have left. Because newspapers are largely generated and sustained by advertising, and it’s typically the job of advertising to make things sound brand-new even when they’re simply or merely upgraded. [1/16/2012]

Read more

Read more

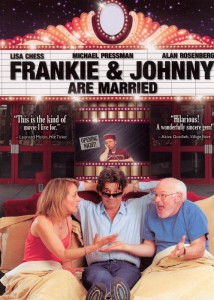

From the Chicago Reader, May 18, 2001. — J.R.

Normally, viewing 16 shorts in a row is a bit like following ice cream with pickles, cheese dip, key lime pie, lima beans, bread pudding, and spinach. But this lineup is relatively homogeneous in its strangeness — evident in the actor’s monologue filmed by children that constitutes David Cronenberg’s 35-millimeter Camera (2000, 6 min.), Joshua Pritzker’s weird animation Small Car (7 min.), Jim Finn’s Communista (a compilation of three songs), and most of all, Todd Rohal’s wildly surrealist Knuckleface Jones (1999, 13 min.), which offers the most peculiar and dreamlike cross-gendered sex I can recall seeing. There are more surrealist high jinks in the other animated shorts, some featuring puppets and clay animation, plus an experimental black-and-white documentary (Trevor Arnholt’s 13-minute digital video The Composer) and a parodic trailer starring Eric Stoltz and Tate Donovan (Paul Harrison’s Jesus and Hutch). The program runs about 95 minutes, and overall it’s not a bad lineup. Biograph, Friday, May 18, 8:00, and Sunday, May 20, 1:00.

— Jonathan Rosenbaum

Read more

Read more

From the October 2008 issue of Artforum. (This is also reprinted in my 2010 collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia.) — J.R.

No major figure in postwar Japanese cinema eludes classification more thoroughly than Nagisa Oshima. The director of twenty-three stylistically diverse feature films since his directorial debut in 1958, at the age of twenty-six, Oshima is, arguably, the best-known but least understood proponent of the Japanese New Wave that came to international prominence in the 1960s and ’70s (though it is a label Oshima himself rejects and despises). Given the size of his oeuvre and the portions that remain virtually unknown in the West — including roughly a quarter of his features and most of his twenty-odd documentaries for television — the temptation to generalize about his work must be firmly resisted. Read more

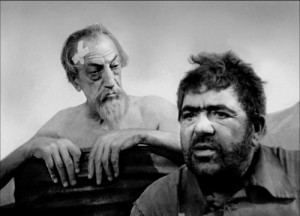

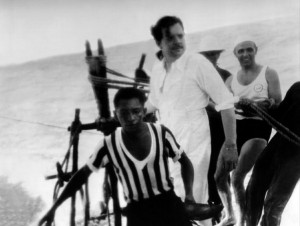

This beautiful photograph, which I’m told has never been published before, was given to me by his maternal niece Rina Chakravarti in Toronto, at the Lightbox, shortly before I gave an introduction to a restored, gorgeous print of Ghatak’s 1960 masterpiece, The Cloud-Capped Star. It was taken taken in 1946 in Baikunthapur, Madhya Pradesh.

As one can (arguably) see from the photo below, of Niranjan Roy — the male lead of The Cloud-Capped Star, who plays the character Sanat — there’s a certain resemblance. [9-11-12]

Read more

From Scenario, Spring 1999, Vol. 5, No. 1. -– J.R.

The recent video release and cable premiere of Louis Feuillade’s silent French serial Les Vampires (1915- 1916), making it widely available in the United States for the first time in 80-odd years, clarifies the origins of the paranoid thriller in a particularly acute way. All the basic elements that we associate with movie conspiracies are fully present in Les Vampires, at least in some rudimentary form: high-tech surveillance techniques, secret lairs, hidden wall panels, intricately concealed weapons, elaborate disguises, diverse forms of mind and memory control.

This arsenal of paraphernalia and technology, suggesting that the ordinary world isn’t quite what it appears to be and that everyday life is full of concealed plots and hidden dangers, is surely a staple of this century that didn’t have to wait for video surveillance or the digital revolution before it took over people’s imaginations. Though the political casts of the designated villains fluctuate wildly according to the ideology of the country and period — ranging from the anarchist Vampire gang to the red spies of Cold War thrillers, to the nearly invisible capitalist tycoons of Cutter’s Way (1981), to the smug government bureaucrats in the significantly titled Enemy of the State — the evil designs remain more or less the same. Read more

For me the most interesting “ten best” list included in the January-February 2009 issue of Film Comment is the dozen titles offered by my favorite Japanese film critic, Shigehiko Hasumi. And what’s especially interesting about his list is the inclusion of Leos Carax’s Merde — the middle episode in the three-part feature Tokyo! (2008), flanked by contributions from Michel Gondry and Joon-ho Bong. Decidedly over-the-top in both theme and style as well as execution, and starring former circus acrobat Denis Lavant, who also plays the lead role in Carax’s first three features — an actor who’s surely even more important to this filmmaker’s work than Jean-Pierre Léaud was to the early features of Truffaut — Merde is a provocation and something of an anomaly, even for someone as eclectic as Carax. (It’s also his first film of any length since his 1999 Pola X, his only major film without Lavant.)

Clearly inspired, at least in its opening stretches, by Jean-Louis Barrault in Jean Renoir’s odd Jekyll-and-Hyde adaptation, Le Testament du docteur Cordelier (1961) [see below], Lavant plays a monster who emerges from the Tokyo sewers to wreak random and violent havoc on Tokyo pedestrians until he gets brought to trial, where he gets defended by an equally strident French lawyer (Jean-François Balmer, in a performance that’s almost as extravagant as Lavant’s). Read more

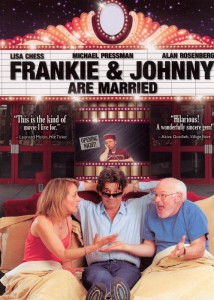

From the Chicago Reader (December 10, 2004). — J.R.

A fascinating blend of fiction and documentary, this feature by Michael Pressman chronicles his emotionally complicated LA production of Terrence McNally’s play Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune. Pressman’s wife, Lisa Chess, costarred in the show with his old friend Alan Rosenberg, until difficulties with Rosenberg convinced Pressman to take over the part himself. These three and many other people (including Kathy Baker and Hector Elizondo) play themselves in the movie, which only begins to suggest the ambiguities Pressman exploits to the utmost. Emerging from all this is a fascinating look at the nuts and bolts of theater work and an often hilarious depiction of how personal neuroses help and hinder it. R, 95 min. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 16, 2004). As much as I share my colleagues’ admiration [in 2012] for Jafar Panahi’s This is Not a Film, I must confess that I find it both depressing and somewhat insulting to Panahi that this is receiving more attention and praise in some quarters than his full-fledged films ever did, including such masterpieces as The White Balloon, The Circle, and Crimson Gold (not to mention Panahi’s more inventive and fruitful 2013 Closed Curtain, made under the same constraints as This is Not a Film). Which is why it seems worth reviving my review of the latter film. — J.R.

Crimson Gold **** (Masterpiece) Directed by Jafar Panahi Written by Abbas Kiarostami With Hussein Emadeddin, Kamyar Sheissi, Azita Rayeji, Shahram Vaziri, Ehsan Amani, and Pourang Nakhayi.

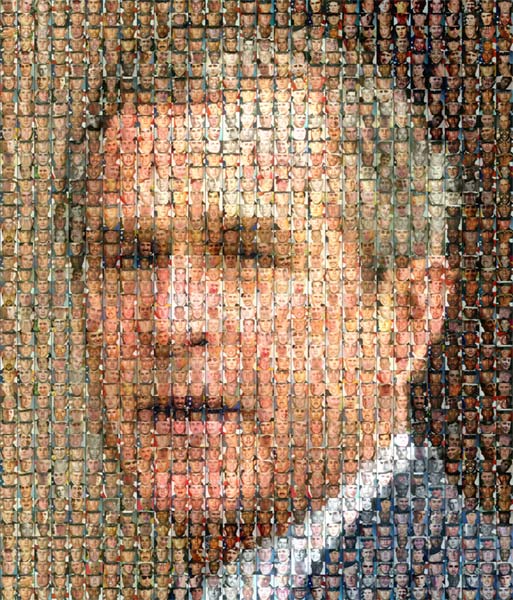

“War President” is an image. It is not a textual statement or rhetorical argument. An image is like an empty room and any message that one reads in that room necessarily came in the baggage one carried when one walked in the door. If I made an image of George Washington composed of images of the American dead from the revolution, would viewers likely take that image as an indictment of Washington? Read more

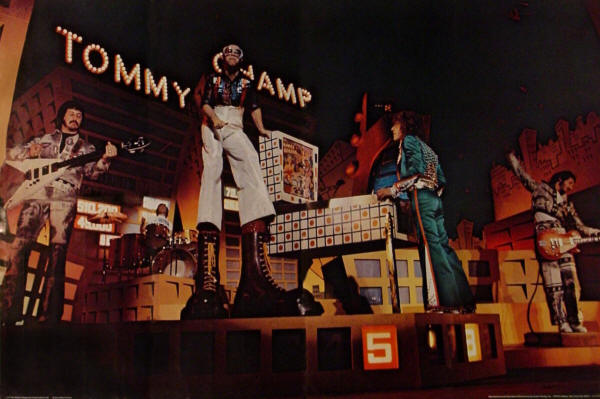

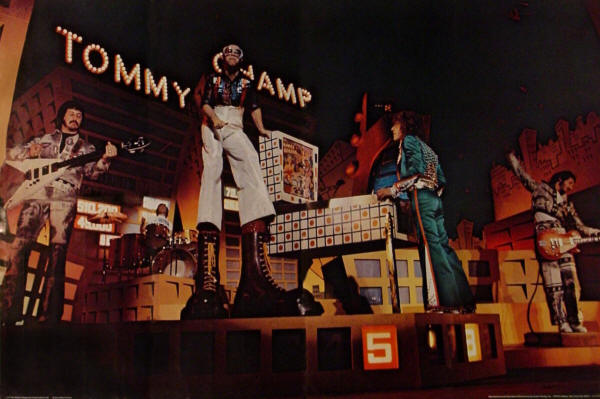

From Monthly Film Bulletin, April 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 495). — J.R.

Tommy

Great Britain, 1975 Director: Ken Russell

Cert-AA. dist-Hemdale. p.c—The Robert Stigwood Organisation.

exec. p-Beryl Vertue, Christopher Stamp. /;Robert Stigwood, Ken

Russefl. assoc. p-Harcy Benn. p. manager-John Comfort. asst. d-

Jonathan Benson. sc-Ken Russell. Based on the rock opera by Pete

Townshend and the Who. addit. Material–John Entwistle, Keith Moon.

ph–Dick Bush, Ronnie Taylor. In colour. sp. ph. effects–Robin Lehman.

ed—Stuart Baird. a.d–John Clark. set dec–Paul Dufficey, Ian Whittaker.

sp. Effects–Effects Associates, Nobby Clarke,_Carygra Effects. m/songs–

“Captain Walker Didn’t Come Home”. “It’s a Bov !” “’51 is Going to be a

a Good Year”, “What About the Boy ?”, “See Me, Feel Me”, “The

Amazing Journey”, “Christmas”, “The Acid Queen”, “Do You Think

It’s All Right?”, “Cousin Kevin”, “Fiddle About”, “Sparks”, “Pinball

Wizard”, ‘Today It Rained Champagne” ,”‘There’s a_Doctor” , “Go to the

Mirror”, “Tommy Can You Hear Me !’” “Smash the Mirror”, “I’m Free”,

“Miracle Cure”, “Sensation”, “Sally Simpson”, “Welcome”, “Deceived”,

“Tommy’s Holiday Camp”, “We’re Not Gonna Take It”, “Listening to

You” by Pete Townshend and The Who [Roger Daltrey,John Entwistle,

Keith Moon, “Eyesight to the Blind” by Sonny Boy Williamson. m.d–

Pete Townshend. musicians-Elton John, Eric Clapton, Keith Moon,

John Entwistle, Ronnie Wood, Kenny Jones, Nicky Hopkins, Chris

Stainton , Fuzzy Samuels, Caleb Quayle, Mick Ralphs, GRaham Deakin,

Phil Chen, Alan Ross, Richard Bailey, Dave Clinton, Tony_Newman,

Mike Kelly, Dee Murray, Nigel Ollson, Ray Cooper, Davey_Johnstone,

Geoff Daley, Bob Efford, Ronnie Ross, Howie Casey. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 17, 1989). — J.R.

APARTMENT ZERO

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Martin Donovan

Written by Donovan and David Koepp

With Colin Firth, Hart Bochner, Dora Bryan, Liz Smith, Fabrizio Bentivoglio, James Telfer, Mirella D’Angelo, Juan Vitali, and Francesca d’Aloja.

Although it qualifies technically as an American movie, Martin Donovan’s ambitious, disturbing thriller Apartment Zero is one of those international hodgepodges that are somewhat disorienting almost by definition. Set in Buenos Aires, made with actors and technicians from three continents, and filmed in English by an Argentinean director who has lived mainly in Italy and England since the 70s, it has the sort of multinational sprawl that only a strong script and a forceful style could hold together. Fortunately, Apartment Zero has both script and style in spades. It may not be to everyone’s taste, but to me it’s an exciting piece of controlled cinematic delirium.

I first encountered this movie at a midnight screening at the Berlin Film Festival last February, having been guided to it by a perceptive rave in Variety by Todd McCarthy. Ever since then I’ve been wondering when and how it would eventually turn up in Chicago. It lacks most of the usual commercial calling cards (big stars, lovable nerds, genre cliches, babies, body switches, Spielberg lighting), it was passed up by the New York and Chicago film festivals, and it didn’t seem the sort of picture that Vincent Canby would like. Read more

Written for the Second Run DVD of Pedro Costa’s Casa de Lava, released in the U.K. in 2012, and developed from separate articles in the Chicago Reader, November 15, 2007, and the Portuguese collection cem mil cigarros: OS FILMES DE PEDRO COSTA, edited by Ricardo Matos Cabo, Lisboa: Orfeu Negro, 2009. — J.R.

The cinema of Pedro Costa is populated not so much by characters in the literary sense as by raw, human essences — souls, if you will. This is a trait he shares with other masters of portraiture, including Robert Bresson, Charlie Chaplin, Jacques Demy, Alexander Dovzhenko, Carl Dreyer, Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, and Jacques Tourneur. It’s not a religious predilection but rather a humanist, spiritual, and aesthetic tendency. What carries these mysterious souls, and us along with them, isn’t stories — though untold or partially told stories pervade all of Costa’s features. It’s fully realized moments, secular epiphanies.

Born in Lisbon in 1959, Costa grew up, by his own account, without much of a family. Speaking about O sangue, his first feature, he admitted that there was a personal aspect in his concentration on the incomplete family in that film “because I never really had a family. Read more

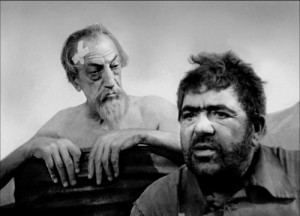

Written originally for Trafic no. 12 (Fall 1994), where it appeared in French translation, translated by Bernard Eisenschitz; all three letters first appeared in English in Persistence of Vision No,. 11, 1995. — J.R.

June 13, 1994

Dear Bill,

It’s good to have all your multifaceted thoughts about It’s All True, which makes your letter worth the long wait. I especially value what you have to say regarding the political implications of the film in the 1940s as well as the 1990s, because it seems that those implications have mainly eluded critics in both decades. As you well know, it wasn’t until Robert Stam published “Orson Welles, Brazil, and the Power of Blackness” in the seventh issue of Persistence of Vision (1989), with corroborating essays by both Catherine and Susan Ryan, that it finally became clear, forty-odd years after the event, that part of what was rattling so many studio executives and Brazilian government officials alike about Welles’s behavior in Rio was his particular interest in blacks. Maybe you’re right that he wasn’t a radical, but if It’s All True had been completed and released in the early 1940s, it still might have offered a radical precedent: three Latin American stories focusing on non-white heroes. Read more

Written originally for Trafic no. 12 (Fall 1994), where it appeared in French translation, translated by Bernard Eisenschitz; all three letters first appeared in English in Persistence of Vision No,. 11, 1995. — J.R.

June 7, 1994

Dear Jonathan,

Sorry to have been so long replying. As you say, much has happened since you wrote your letter. We both started out years ago in a series of polemical articles to correct received ideas of Welles, and we seem to be making progress. This Is Orson Welles and It’s All True will be more widely read and seen than those articles ever were. Already Richard Combs, writing about f for fake in the January–February 1994 Film Comment, acknowledges the thesis of Welles the independent filmmaker advanced by you in “The Invisible Orson Welles” as a corrective to the idea of Welles the great failure, then proceeds to propose a new theory of the work, with failure of another kind inscribed in it from the start. That article would have been unthinkable a few years ago, when what might be called the vulgar theory of failure was still dominant.

The work on the Welles legacy is going well: Oja is set to co-direct a documentary that will include several of the important fragments; The Deep and The Other Side of the Wind may be finished in the next couple of years, and hope springs eternal where The Merchant of Venice is concerned. Read more

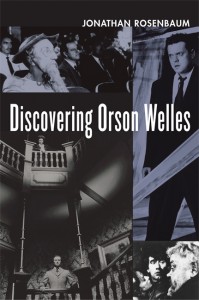

Written originally for Trafic no. 12 (Fall 1994), where it appeared in French translation, translated by Bernard Eisenschitz; all three letters first appeared in English in Persistence of Vision No,. 11, 1995. The version here, including my introduction, comes from Discovering Orson Welles. — J.R.

This chapter -— the longest in my 2007 book Discovering Orson Welles, and in some ways my favorite -— was originally written for the French quarterly Trafic, and in fact was the first thing I ever wrote specifically for that magazine. The late Serge Daney (1942–1994) —- whom I’d known since his stint as editor of Cahiers du cinéma, when he’d gotten me to serve briefly as its New York correspondent (after Bill Krohn had shifted from that post to the same magazine’s Los Angeles correspondent) -— died of AIDS not longer after launching Trafic, and by my own choice, my first contribution, a memoir about working for Jacques Tati (see “The Death of Hulot” in my collection Placing Movies), was something I’d already written for and published in Sight and Sound. My second contribution was my brief introduction to Orson Welles’s “Memo to Universal”, an “outtake” from This Is Orson Welles that had been accepted by Serge’s coeditors (Raymond Bellour, Jean-Claude Biette, Sylvie Pierre, and Patrice Rollet) during Serge’s illness. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 3, 2003). — J.R.

Broadly speaking, this is Richard Linklater’s French Cancan — that is to say, a humanist’s joyful exploration of the musical in which the actors’ personalities resonate as much as the characters they play. Or maybe it’s what Jean Renoir might have come up with if he’d remade Don’t Knock the Rock and cast 12-year-olds as the musicians. Though this seems like a personal film, Linklater was hired to direct a cannily commercial script by Mike White, about a rock ‘n’ roll loser (Jack Black) who, fired from his job and his band, impersonates his wimpy substitute-teacher roommate (White) to land a teaching position at an upscale elementary school. This infantile character hasn’t got a thought in his head except for rock music, but somehow he becomes a model teacher, and through stealth and sheer perseverance he turns his fifth-grade class into an inspired gang of rockers. The kids, all real musicians performing, are wonderful, and so is Black; Joan Cusack is both charming and funny as the principal. 108 min. Century 12 and CineArts 6, Chatham 14, City North 14, Crown Village 18, Ford City, Gardens 1-6, Gardens 7-13, Lawndale, Lincoln Village, Norridge, North Riverside, 600 N. Read more