Piaf & German porn

From Oui (September 1974). –- J.R.

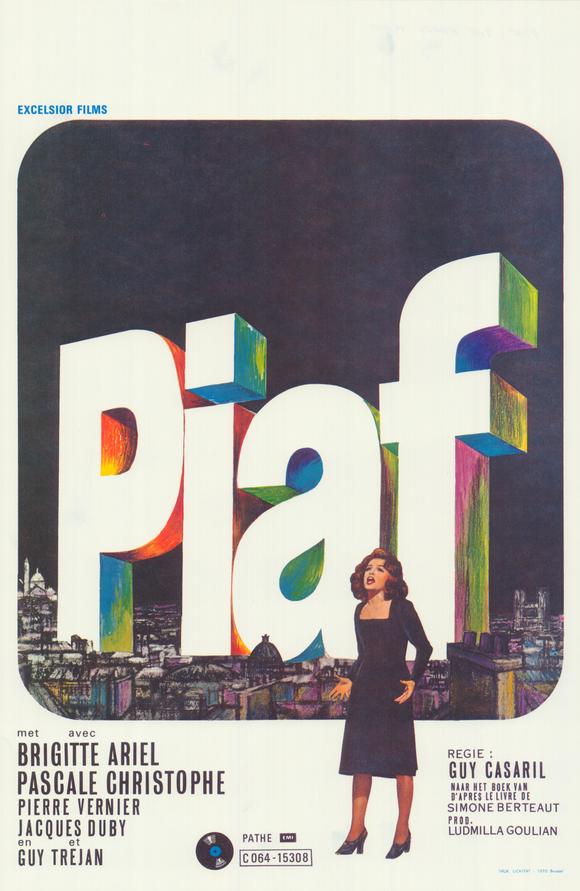

Piaf. In her life and in her music’ Edith Piaf is probably the closest thing France has had to a Billie Holiday. It shouldn’t come as a surprise, then, that a feature-length fiction film based on her life gives her the same kind of treatment that Lady Sings the Blues gave to Billie. We begin with Edith’s birth in 1915 in a red-light district of Paris. Abandoned by her mother, she grows up in a provincial whorehouse, Edith starts singing for centimes in street acts with her acrobat father. Then she goes independent and sings on the street while her half-sister, Momone, accompanies her on harmonica.Piaf is menaced by a Montmartre pimp who sells her “protection”. After she gives birth to a bastard daughter who dies in infancy, she gradually makes her way up the ladder from a dive in Pigalle to a Champs-Elysées niqht club. The plot is taken from a “fictionalized” biography by Simone Berteaut, the real-life Momone. Newcomer Brigitte Ariel plays Piaf, although the singing voice belongs to Betty Mars in both the French and English versions of the film. Guy Casaril, the director, serves it all up in something akin to the American bio-pic Style: Edith sings her heart out as the camera sails up into the sky. Read more