Unfortunately, Richie’s division of Ozu into successive stages of ‘creation’ inevitably leads to the erection of a Platonic ideal, an all-purpose model of ‘the’ Ozu film — an unrigorous model indeed when what one concretely has to contend with are films, each with its own peculiar set of conditions and stresses. Since Richie has more production details about the later films, these tend to dictate most of the dimensions of the model, and the lost films implicitly become subsumed in the same homogenising process whenever Richie speaks about the entire body of the work. The usual approach is to lump together examples of certain aspects or procedures, leading to the formulation of such generalities as ‘the Ozu family’. This results in a profusion of catalogues, some quite nonsensical in presumed meanings and applications: ‘Another pastime to which the Ozu family is addicted is toenail cutting, an activity which seems worth mentioning because it occurs possibly more often in Ozu’s pictures (Late Spring, Early Summer, Late Autumn) than in Japanese life.’ In the long run, individual works are made to seem important or unimportant insofar as they help or fail to exemplify the hypothetical model.

Problem No. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 5, 2007). — J.R.

A taciturn ex-convict (nonprofessional actor Argentino Vargas) leaves prison after a 20-year sentence and crosses a tropical forest by boat and on foot to find his daughter. This 2004 feature is the second by Lisandro Alonso (La Libertad), a singular and essential figure of the Argentinean new wave; he’s not quite the minimalist some claim, but he can make the simple act of filming feel so monumental that storytelling seems secondary. The hero’s crime, though indicated in the film’s title and opening shot, is acknowledged only fitfully in the spare dialogue, and his killing and gutting of a goat is shown with the same matter-of-factness as his visit to a prostitute. Vargas and the wilderness are such great camera subjects that a sense of quiet revelation is nearly constant. In Spanish with subtitles. 82 min.

Read more

Read more

From Sight and Sound (January 2007). – J.R.

In order to write briefly about five films that I first saw in 2006 that are especially important to me, I have to violate a taboo against acknowledging works that aren’t (yet) readily available. More specifically, the first two on my list haven’t yet been seen very widely outside of film festivals and/or the countries where they were made, while the last two, even more rarefied, have only been shown under special circumstances, in both cases because their filmmakers are under no commercial pressures to release them and would like to oversee and monitor their exhibition. Although I’m aware that this may irritate some readers, I’d rather address them like adults than succumb to the infantile consumerist model of instant gratification, according to which works should be known about only when they can be immediately accessed. After all, some pleasures are worth waiting for.

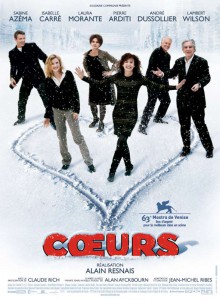

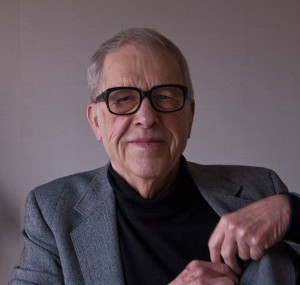

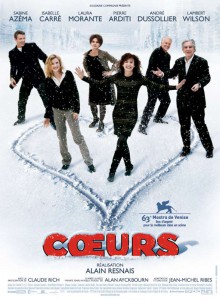

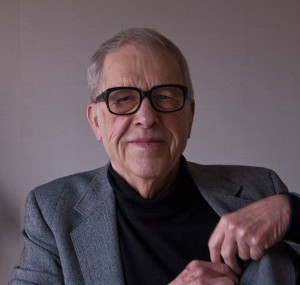

Coeurs

Alain Resnais’ dark, exquisite, and highly personal adaptation of Alan Ayckbourn’s Private Fears of Public Places, which I saw at film festivals in Venice and Toronto, is eloquent testimony both to how distilled his art has become at age 84 and how readily Ayckbourn’s examples of English repression can be converted into French equivalents. Read more

For the beginning of this article, go here.

While one could hardly claim that Days of Youth is a major work, it is at the very least an arresting one, and some of its comedy is on a par with the wonderful opening sequence of Passing Fancy (1933) at a naniwabushi recital (when a stray purse gets surreptitiously picked up, investigated, and tossed around like a beanbag by various spectators until the. entire assemblage, reciter included, is dancing about from an attack of lice). One would expect, then, that any serious Ozu scholar would pay some heed to it. Yet all that Richie has done in Ozu — apart from noting at one point that, like all of Ozu’s subsequent films, it shows actors directly facing the camera — is to expand his original commentary on the film (in Film Comment, Spring 1971) from five words (‘A student comedy about skiing’) to seven: ‘Another student comedy, this one about skiing.’ And if one searches in his book for something about Tatsuo Saito — an actor who went on to play the father in I Was Born, But . . . (1932), and figured centrally in several of the twenty other Ozu films where he appeared — one finds that he isn’t even listed in the index; in fact, the only reference to him in the entire book is the observation that he ‘keeps rubbing his hip during various scenes’ in Tokyo Chorus. Read more

From the Summer 1975 issue of Sight and Sound. Due to the length of this piece, I’m running it in three parts. I’ve hesitated for years about reprinting this because of its harshness towards the very amiable and sweet-tempered Donald Richie (1924-2013), whom I eventually met and befriended in Tokyo a quarter of a century after writing this piece (and who generously forgave me for having written it after I offered an apology). Even though I can’t say I agree with everything I wrote here — I’m especially dubious about some of Burch’s arguments (and many or all of the passages I quote here from To the Distant Observer, which he was writing at the time, subsequently got edited out of the manuscript) — it holds up better than I suspected it would, which is why I’m posting it here. I tend to think now that the failings of Richie’s book on Ozu are more institutional than personal — that is, a reflection of his unfortunate virtual monopoly on critical discourse in English about Japanese cinema during that period. — J.R.

A few years ago in New York, a lecture by Henri Langlois was announced at the Museum of Modern Art under the rough heading — I quote from memory — of ‘Why We Know Nothing About Cinema’. Read more