Splitting Images [THREE LIVES AND ONLY ONE DEATH & LOST HIGHWAY]

From the Chicago Reader (February 28, 1997). — J.R.

Three Lives and Only One Death

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Raul Ruiz

Written by Ruiz and Pascal Bonitzer

With Marcello Mastroianni, Anna Galiena, Marisa Paredes, Melvil Poupaud, Chiara Mastroianni, Arielle Dombasle, Feodor Atkine, and Lou Castel.

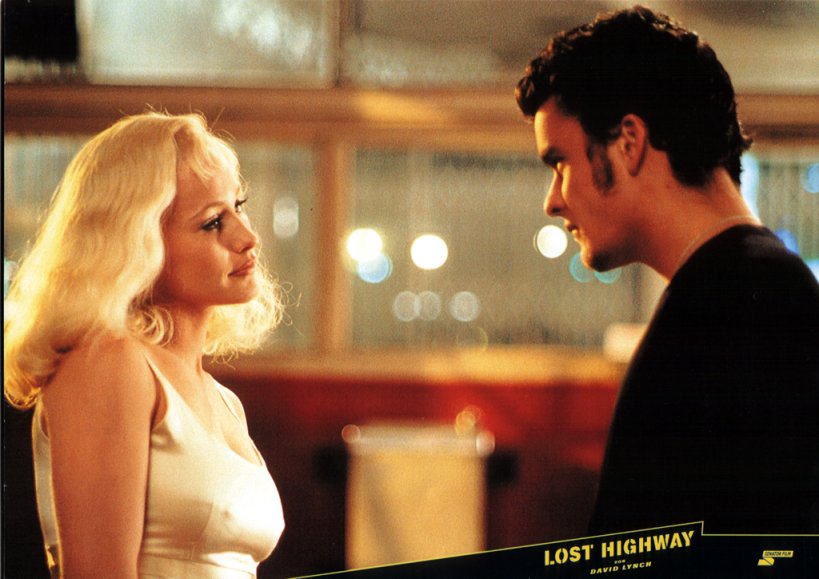

Lost Highway

Rating *** A must see

Directed by David Lynch

Written by Lynch and Barry Gifford

With Bill Pullman, Patricia Arquette, Balthazar Getty, Michael Massee, Robert Blake, Gary Busey, Lucy Butler, Robert Loggia, and Richard Pryor.

By coincidence, two major features by two of the most talented postsurrealist filmmakers open this week, both convoluted parables about heroes with multiple identities. Though Raul Ruiz and David Lynch are separated by a world of differences — political, cultural, national, intellectual, and temperamental — both are expanding the options in filmmaking as well as filmgoing. Each offers a different kind of roller-coaster ride that manages to be bewildering, provocative, kaleidoscopic, scary, visually intoxicating, and funny.

Ruiz — a Chilean who moved to Paris in 1974 and who makes movies all over the world (in France, Italy, Taiwan, and the U.S. in the past year alone) — has made 90-odd films and videos to date, though he’s only five years older than Lynch. Read more