From the Chicago Reader (March 21, 2003). — J.R.

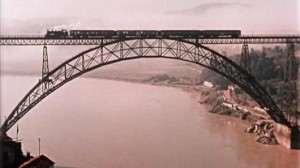

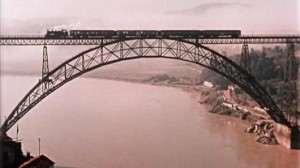

Manoel de Oliveira’s 2001 masterpiece explores the Portuguese city where he’s lived for more than 90 years, though it concentrates on the first 30 or so, suggesting that his childhood must have lasted a very long time. It’s a remarkable film for its effortless freedom and grace in passing between past and present, fiction and nonfiction, staged performance and archival footage (including clips from two of his earliest films, Hard Work on the River Douro and Aniki-Bobo) while integrating and sometimes even synthesizing these modes. He’s mainly interested in key images, music, and locations from the Eden of his privileged youth, and some of the film’s songs are performed by him or his wife — though we also get a fully orchestrated version of Emmanuel Nunes’s Nachtmusik 1. In Portuguese with subtitles. 61 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

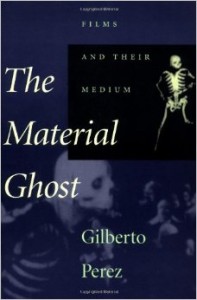

I can’t remember the first time I met Gil Perez, but the first time I got in touch with him, which must have been in the late 60s, it was to reprint a remarkable essay of his about Murnau that had appeared in Sight and Sound for an anthology I was editing called Film Masters, a book that for various complex reasons never came out (although, if memory serves, it twice reached the galley-proof stage). I do recall that Gil was still a theoretical physicist at the time, in the U.S. but still relatively fresh from Havana, and he was most likely making his academic transition to film studies and film theory when we eventually met in New York. (See his Introduction to his magisterial 1998 The Material Ghost, “Film and Physics,” for more details.) Years later, circa the early 80s, we became neighbors in Hoboken, living only a few blocks apart, and we remained loosely in touch for the remainder of his life, during his various stints at William Paterson, Princeton, Harvard, Missouri, and, most permanently, Sarah Lawrence, where he ran the film history program.

A slow and methodical writer, but also a prolific one, Gil wrote frequently about film for the The Hudson Review, The Yale Review, and the London Review of Books and less often for film and academic journals, and I was often envious of the way he was both welcome and able to hold his own as a public intellectual with a literary sensibility in those and similar venues, such as The Nation. Read more