A Notorious French Conspiracy Exposed

The following sentence is spoken in Variety writer Peter Debruge’s informative and interesting audiovisual essay “Abel & Gordon The Quest for Burlesque,” included on Arrow Academy’s Blu-Ray of Lost in Paris (to be released on December 4):

“There are all kinds of styles from within the burlesque tradition, from the blatantly silly likes of Jerry Lewis, for which the French notoriously have a far greater appreciation than Americans do, to the more refined French comedian Pierre Etaix, who did most of his pratfalls in a suit and hat.”

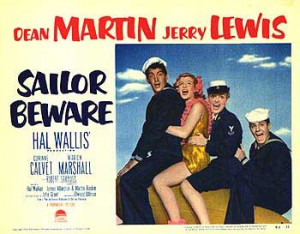

There are two rather strange assumptions lurking behind this commonplace sentence. Let me bypass the one that defines refinement strictly according to class and clothes and focus on the seemingly more innocuous one about Lewis, which in fact exposes the secret conspiracy accounting for the release of two to three Jerry Lewis features a year during the 1950s — namely, the fact that France was surreptitiously funneling millions of dollars in production costs to Paramount and Hal Wallis so that they could jointly service the French market, all unbeknownst to Americans, who were staying away from the Martin and Lewis pictures in droves. Consequently, one can only surmise that the estimated 80 million people who saw Sailor Beware, Martin and Lewis’s fourth feature, in 1952, consisted of the entire population of France and only 20 million or so Americans, and the fact that Living It Up a year later made more money than Singin’ in the Rain, On the Waterfront, or The African Queen can only be explained by the hyperbolic activities of Lewis’s French fans. Read more