In The Mood For Love

From the Chicago Reader (January 2, 2001). — J.R.

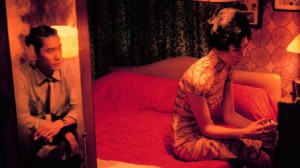

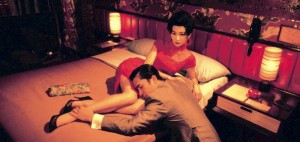

A brooding chamber piece (2000) about a love affair that never quite happens. Director Wong Kar-wai, Hong Kong’s most romantic filmmaker, is known for his excesses, and in that sense the film’s spareness represents a bold departure. Claustrophobically set in adjacent flats in 1962 Hong Kong, where two young couples find themselves sharing space with other people, it focuses on a newspaper editor and a secretary at an export firm (Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung, the sexiest duo in Hong Kong cinema) who discover that their respective spouses are having an affair on the road. Wong, who improvises his films with the actors, endlessly repeats his musical motifs and variations on a handful of images, rituals, and short scenes (rainstorms, cab rides, stairways, tender and tentative hand gestures), while dressing Cheung in some of the most confining (though lovely) dresses imaginable, whose mandarin collars suggest neck braces. In Cantonese, French, Mandarin, and Spanish with subtitles. PG, 98 min. (JR)