From the March 1, 1988 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

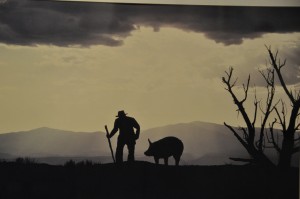

Robert Redford’s second feature as director (after Ordinary People) describes the elaborate consequences when a Chicano handyman in New Mexico (Chick Vennera) illegally irrigates his parched bean field with water earmarked for a major development. Fairly choked with good intentions, whimsy, touches of fantasy, and cardboard liberal stereotypes, this 1988 release does for Mexicans what Louis Malle did for Jews or Walt Disney did for mice — slowly, and at great length. The results are a bit like a translation of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s magical realism by Mortimer Snerd, with pretty landscapes. John Nichols adapted his own novel, assisted by David Ward; with Ruben Blades, Richard Bradford, Sonia Braga, Julie Carmen, James Gammon, Melanie Griffith, John Heard, Carlos Riquelme, Daniel Stern, and Christopher Walken. R, 118 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the April 1, 1997 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

An adventurous and sometimes sexy (if only fitfully successful) 1996 adaptation of Louise Kaplan’s celebrated nonfiction book, directed by Susan Streitfeld from a script she wrote with Julie Hebert. Streitfeld focuses on a successful single prosecutor (British actress Tilda Swinton, displaying an impeccable American accent) as she waits to discover whether she’s been appointed as a judge, her kleptomaniac-scholar sister (Amy Madigan), the prosecutor’s boyfriend, a lesbian psychotherapist she has a fling with, and other people in her orbit. Oscillating between everyday events in her life and her dreams and fantasies, the film is much more successful with the former than with the latter, which often get heavy-handed and obscure. But the freshness of Streitfeld’s approach toward gender anxiety and social conditioning fascinates even when the overall clarity diminishes. Not for everyone, but those who like it will probably like it a lot. With Karen Sillas, Clancy Brown, Frances Fisher, Laila Robins, Paulina Porizkova, and Dale Shuger. (JR)

Read more

From the May 1, 1994 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

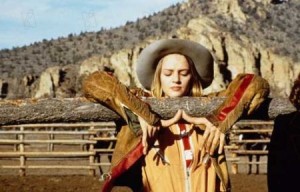

Gus Van Sant adapts Tom Robbins’s comic, countercultural novel of the 70s by boiling away half of the subplots, eliminating the interpolated essays, and upgrading the lesbian romance, and while the results are both cheerful and occasionally inventive, they can’t hold a candle to his previous features (Mala Noche, Drugstore Cowboy, My Own Private Idaho); too many jokey asides and cameos — not to mention an overdose of plot — keep getting in the way. Sissy Hankshaw (Uma Thurman) puts her abnormally large thumbs to use in hitchhiking and winds up at a ranch in Oregon among a band of renegade cowgirls. With John Hurt, Angie Dickinson, Pat Morita, Lorraine Bracco, and Rain Phoenix. (JR)

Read more

Read more

THE RACK, written by Stewart Sterm and Rod Serling, directed by Arnold Laven, with Paul Newman, Wendell Corey, Edmond O’Brien, Walter Pidgeon, Anne Francis, Lee Marvin, and Cloris Leachman (1956, 100 min.)

TIME LIMIT, written by Henry Denker and Ralph Berkey, directed by Karl Malden, with Richard Widmark, Richard Basehart, Dolores Michaels, June Lockhart, Rip Torn, Martin Balsam, Carl Benton Reid, and James Douglas (1957, 96 min.)

I’ve recently reseen these two taut black and white 50s melodramas about the impending courtmartials of American POWs in North Korea who broke under torture, including brainwashing, and became traitors–characters played respectively by Paul Newman and Richard Basehart, and interrogated by Wendell Corey and Edmond O’Brien in the first film, Richard Widmark in the second. Indeed, there are so many close similarities and parallels between these films and their existential issues that I’ve often mixed them up in my memory, although it’s now clear after reseeing them that Time Limit, the only film ever directed by Karl Malden, is by far the better of the two. The Rack is adapted by Stewart Stern from a 1955 TV drama by Rod Serling that aired on the United States Steel Hour; Time Limit is adapted by Henry Denkler from a 1956 play that he coauthored with Ralph Berkey. Read more

From the February 1, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Peter Bogdanovich’s bright 1972 screwball comedy, patterned after Bringing Up Baby and decked out with lots of references to silent slapstick, plants dim musicologist Ryan O’Neal and freewheeling kook Barbra Streisand in San Francisco and then piles on the comic complications, with assistance from Madeline Kahn, Austin Pendleton, John Hillerman, Randy Quaid, and Kenneth Mars. Much of the slapstick is deftly executed, but there is one unfortunate undertone — ordinary, unassuming workers tend to be the fall guys more often than the pompous rich (a factor that distinguishes this comedy from most of Bogdanovich’s classic sources), although O’Neal’s character, who stays at the Hilton, certainly has his share of pratfalls. Streisand sings a fabulous version of “You’re the Top” behind the credits, and the busy script by Buck Henry, Robert Benton, and David Newman keeps things moving, but the spirit of pastiche keeps this romp from truly rivaling its sources. G, 94 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more