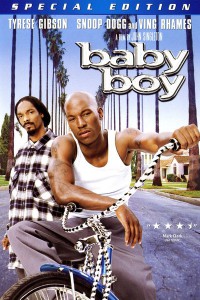

Baby Boy

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 2001). — J.R.

Like John Singleton’s other features, this is far from flawless; at 129 minutes it’s longer than it needs to be, and the music hits you like a sledgehammer at moments when any music at all is redundant and something of an insult. But the characters are so full-bodied and the feelings so raw and complex that I’d call this the best thing he’s done to dateby which I mean the most convincing and serious, telling us at least as much about everyday life in South Central Los Angeles as did Boyz N the Hood, his first movie. The title character, well played by Tyrese Gibson, is a 20-year-old with a pronounced Oedipus complex who lives with his 36-year-old mother (A.J. Johnson), has fathered two kids with separate girlfriends (Taraji P. Henson and Tamara LaSeon Bass), and starts to feel crowded when his mother falls for a reformed gangster (Ving Rhames, also especially good). Sexually explicit both visually and aurally, this shows rare inventiveness in exploring one character’s fantasies during an orgasm. With Omar Gooding and Snoop Dogg. (JR) Read more