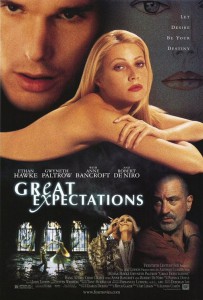

Great Expectations

From the Chicago Reader (January 19, 1998). — J.R.

A reductio ad absurdum of the recent trend of idea-starved producers to plunder 19th-century English fiction — a movement that to my mind has justified itself only with Clueless, and in this case makes Charles Dickens look like a weak second cousin to John Grisham. In fact, so little of the novel is dealt with in this updated adaptation, and so much of that little is mauled, that it might have made more sense to do a remake of Youngblood Hawke, the sort of wet dream this movie is really craving to approximate. Ethan Hawke plays a young gulf-coast artist (formerly known as Pip) lured to the Big City, Gwyneth Paltrow plays cruel Estella (the only character allowed to keep the same name), and Anne Bancroft can’t be blamed for the incoherent version of Miss Havisham assigned to her by Mitch Glazer’s stupid script (though perhaps Robert De Niro, playing the convict, can be blamed for reminding us of Cape Fear). A horrendous effort all around, though a couple of the locations — notably a Venetian Gothic mansion on Sarasota Bay — are suggestive. Alfonso Cuaron, who did a far better job with A Little Princess, directed. Read more