Written in 2010 for the Cinema Guild’s DVD release of Shirin. — J.R.

It doesn’t do justice to Shirin to call it the most conceptual of Abbas Kiarostami’s films. But it probably wouldn’t be an exaggeration to call it the most paradoxical. Not the least of its paradoxes is the way that it simultaneously confronts and defies the specter of commercial cinema, qualifying at once as his most traditional feature and his most experimental. By focusing almost exclusively on the fiction of women watching a commercial feature that we can hear but never see — a feature that in fact doesn’t exist, apart from its manufactured soundtrack — one might even say that Kiarostami, an experimental, non-commercial filmmaker par excellence, is perversely granting the wish of fans and friends who have been urging him for years to make a more “accessible” film with a coherent plot, a conventional music score, and well-known actors.

What’s perverse about this is that the plot in question, while drawing from a traditional epic, a medieval romance widely known in Iran, belongs to an unseen and imaginary film whose on-screen spectators are precisely those well-known actors. (Both men and women comprise this imaginary audience of 110 individuals, although the only viewers featured in close-ups are women.) Yet despite the uses of a conventional plot and music and well-known actors, none of the usual commercial rules for commercial movies are met. Nevertheless, it’s a matter of justifiable pride that Kiarostami manages to fool us with his illusion by using virtually all the skills of a traditional commercial director. Even if we’re non-Iranian viewers, unfamiliar with either the plot or the actors (apart from Juliette Binoche, the only European in the bunch), we’re essentially taken in by all the complicated tricks employed. We accept that these viewers are in a movie theater when Kiarostami is actually filming them all in separate, small clusters in his own living room. And we accept that they’re responding to an actual film even though that imaginary film’s soundtrack was created afterwards. So Kiarostami is perversely showing us he can craft a commercial feature as competently as anyone, even if he’s using all that competence to subvert our expectations.

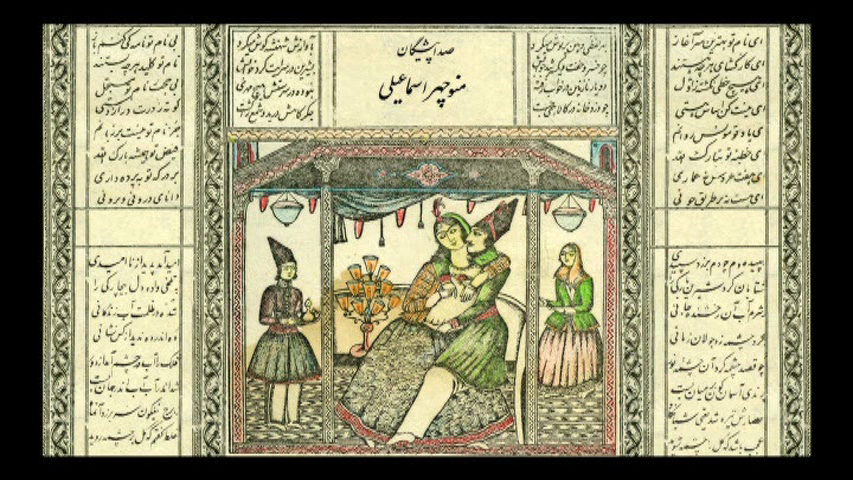

We don’t have to have any familiarity with the medieval poem by Nezami Ganjavi (c. 1141-1209), Khosrow and Shirin, that the imaginary film is based on — a story built around a romantic triangle involving a princess (the title heroine), a prince who becomes a king (Khosrow), and an artist (a mason named Farhad) — in order to appreciate the universality of the film experience being depicted. As if to prove this point, Kiarostami did a preliminary three-and-a-half-minute sketch for this film, Where is My Romeo?, made for the Cannes film festival in 2007, using the same or very similar footage but with the soundtrack of an already existing feature, and a Western one at that, Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet (1968).

Kiarostami’s relation to commercial cinema has always been a rather special one, because he enjoyed the luxury of developing as a filmmaker in relative independence from the usual commercial norms. Having worked in the 60s as a graphic artist — first as a designer of book covers and posters, then as a maker/designer of commercials and credits sequences in the films of others — he was already pushing thirty when the owner of the ad agency he worked for, who also directed the state-run Kanun (the Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, founded by the shah’s wife), invited him to collaborate in setting up that organization’s film unit. And for the next two decades, nearly all of Kiarostami’s twenty-odd films were state-supported educational films made for that unit.

It was only towards the tail end of this period, when Kiarostami made his most influential feature, Close-up (1990) — his first Kanun feature focusing on full-grown adults, a curious docudrama about the arrest and trial of a poor man who was caught impersonating a famous filmmaker, Mohsen Makhmalbaf — that he began to edge away from Kanun’s agenda. But by that time he had already developed a playfully deceptive kind of filmmaking that would serve him well on his subsequent projects, part of which entailed turning non-actors into actors, most of them children and young adults, through various ruses of persuasion. (Prior to Shirin, the only times Kiarostami used professional actors was when he employed Shohreh Aghdashloo in his 1977 Report and Mohammad-Ali Keshavarz as the director in the 1994 Through the Olive Trees.)

To outline the processes that eventually led to Shirin — which almost (but not quite) turns all its actors into non-actors — it might be argued that an important part of his methodology involves treating his performers and his viewers like children, bringing various versions of his ruses to bear on other grown-up subjects. (One might argue, in fact, that the art of treating viewers like children is very much, by and large, the art of Hollywood. If Hollywood as an institution was originally bent on entertaining more than children, it has devolved more and more, over the years, towards treating adult viewers as if they were all kids at heart, in terms of both style and subject matter, at least when it comes to action-adventure, big summer releases, and the like.) Characteristically, this usually entailed working without a fixed script — in many cases generating dialogue that was spontaneous by addressing his actors offscreen and getting them to respond.

In Close-up, Kiarostami exerted his methods of persuasion on all his performers by convincing them to play themselves while re-enacting the crime, arrest, and trial of Hossein Sabzian. He also filmed his own initial meeting with Sabzian in prison, but more ambiguously, he convinced his participants to go beyond re-enactment when he staged some events — most noticeably a meeting between Sabzian and Mohsen Makhmalbaf — that hadn’t previous occurred, and altered variously other details with the cooperation of his cast for the purposes of the film. In Taste of Cherry, which largely consists of dialogues between a driver (Homayoun Ershadi, who also appears as an extra in Shirin) and various passengers seated next to him, Kiarostami filmed the driver and the passengers in separate shooting sessions, each time occupying the adjacent seat himself, so that the drivers and passengers never actually met. His method was either to provoke various responses to his own actions from the passengers or to get Ershadi to repeat his own lines. What emerged from all this — resembling the famous Kuleshov experiment whereby various fictions are created through the juxtaposition of formerly unrelated shots — was a way of fooling both actors and spectators, coaxing them all into involuntary creative collaborations in the creation of various fictions that had the appearance of documentaries. And variations of these same techniques were used in The Wind Will Carry Us (1999).

Shirin builds its own illusions in a related fashion, although this time — as Hamideh Razavi shows in her very instructive “making of” documentary, Taste of Shirin — Kiarostami is most often directing his actors as actors, whether these are on-screen actresses pretending to be film spectators in his living room or other actors recording their voices in a sound studio for the imaginary film. Sometimes he’s offering simple mechanical instructions (“Now, move your eyes to the left, back to the right”; “Can you have a more interrogative tone?”). But on other occasions he’s either asking his actors to reduce the intensity of their acting (in his living room, “Let your eyes smile, not your lips!”, and, in the sound studio, asking an actress to curtail her emotions until the end of her speech) or he’s reverting to his older technique of producing spontaneous, involuntary reactions(such as when he suddenly kicks an empty film can across the floor of his living room in order to cause an actress to flinch) — the same sort of thing he did with nonprofessionals in his earlier features.

For all his experimentation, Kiarostami as a director has always been interested in using cinema to create primal experiences in which our imaginations are vital elements in his bag of tools. I can recall one such experience when I once had the privilege of spending some time in the same living room where Shirin would later be shot, with several other visitors, during the Fajr film festival in 2001. It was there that he offered us a kind of theatrical presentation of some of his recent still photographs of landscapes, exhibited to us in succession to the accompaniment of Bach on his stereo.

During that same visit, I discovered one of his early paintings hanging on the wall — a painting that, from a distance, appeared to be one of those photographs. This reminded me of something he said in an interview the year before: “I personally can’t define the difference between a documentary and a narrative film.” So even Shirin, which might be described as the most fictional of all his fiction films, is ultimately as much a documentary as the others, with our own reflexes and emotions as spectators serving as an essential part of his subject.