From the February 19, 1993 Chicago Reader. I may have underrated this movie. — J.R.

THE MATCH FACTORY GIRL

** (Worth seeing)

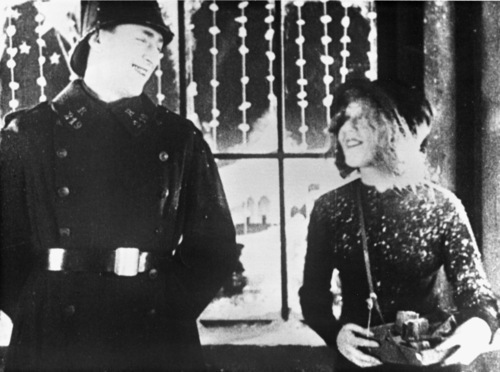

Directed and written by Aki Kaurismaki

With Kati Outinen, Elina Salo, Esko Nikkari, Vesa Vierikko, Reijo Taipale, and Silu Seppala.

Here’s what Finnish writer-director Aki Kaurismaki has written about The Match Factory Girl:

“Suddenly, last spring, I was running aimlessly around the city, talking too much and twisting and shaking my head in the most ridiculous way.

“The next day I spent lying silently under my bed and hated myself bitterly. In revenge I decided to make a film that will make Robert Bresson seem like a director of epic action pictures.

“Later, I named this piece of junk The Match Factory Girl (Tulitikkutehtaan Tytto), as the name is long enough to be easily forgotten.”

A few glosses on the above:

(1) It’s typical of Kaurismaki, who’s given to dandy’s gestures, that we don’t know what he means by “revenge,” though we certainly know what the film’s mousy title heroine, Iris (Kati Outinen), means by it.

(2) The statement clearly asks to be read as a series of hip disclaimers: “running aimlessly,” “talking too much,” “twisting and shaking my head in the most ridiculous way,” “this piece of junk . . . [whose] name is long enough to be easily forgotten.” In one way, it is a refusal of seriousness on the same level as the film; in another, it’s a statement of seriousness on the same level as the film. You can pick either. Or better yet, both.

(3) Even without the help of Aki Kaurismaki, Robert Bresson seems like a director of epic action pictures.

(4) I like The Match Factory Girl, even though, as Kaurismaki implies, it’s easily forgotten — unlike the epic action pictures of Bresson. Even at his worst, Bresson can’t be accused of making stylistic exercises; even at his best, as in this movie, Kaurismaki can’t be accused of making anything else.

(5) I’m unable to determine whether the Finnish title of The Match Factory Girl in any way resembles the Finnish title of Jean Renoir’s silent adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen, The Little Match Girl (1928). If it doesn’t, it should.

After the opening credits on Kaurismaki’s film, which are accompanied by what sounds like a very cold Finnish wind and a literary quotation I’ll get to later, it begins with a virtual industrial documentary on the manufacture of wooden matches — starting with the huge logs that are stripped down into what look like rolls of paper, which are then cut up into individual matches and collected into boxes, which are then wrapped in what looks like brown paper. (As suggested above, Kaurismaki is more adept at loose gestures toward meaning than at being concisely meaningful — impression is all. The important thing is that he treats each shot as if it were a separate expositional unit, a slight advance in information.) Only toward the end of this procedure do we see hands tending the boxes, which a wider shot shows are the hands of Iris.

She is just finishing her shift, and reads a book on the streetcar going home. Then she stops off at a grocer’s for food. Her mother (Elina Salo) is smoking a cigarette and her father (Esko Nikkari) is writing something when she enters the flat; either a radio or TV plays in the background. (We never find out what he’s writing or the fact that he’s her stepfather, as the press materials and credits identify him.) Iris sets the table and prepares dinner, and the three of them eat it in silence. A bit later we see on TV a Helsinki news report of the massacre in Tiananmen Square, among other events of the day; while the mother watches and the father dozes, we see Iris in front of a mirror putting on eyeliner.

Next we find her sitting alone at a nightclub, a wallflower. One shot shows all the women seated on both sides of her leaving either the frame or the nightclub (it hardly matters which) with men, until finally Iris, sipping a soda, is the only thing left in the frame.

As in her first appearance in the film — and in a later shot that triangulates her, a jukebox, and a billiards table — Iris is frequently designated by the camera as a “thing,” an object among objects. This cruelty and irony recall another of Kaurismaki’s models, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who specialized in studied, painterly depictions of working-class victims — characters turned into objects by “society” and Fassbinder alike. Kaurismaki combines some of this feeling for formal composition with a musical sense for pauses and silences in the duration of shots. This means that The Match Factory Girl feels like a formal exercise even when — or perhaps especially when — it evolves from straight melodrama into a hoot.

The next stretch gives us more of the same: Iris all alone reading in a cafe and in a laundromat, doing the ironing while her parents watch TV, back at work tending matchboxes on the assembly line. Then, after she collects her paycheck, she sights a dress in a boutique window and stealthily brings it home with her, folded inside a shoe box. After turning the paycheck over to her parents, she opens the box in another room, takes out the dress, and finds that both parents are watching her. Her father slaps her, says “Whore,” and walks out of the frame; her mother says, “Take it back.”

Cut to Iris renting a public shower stall while carrying the shoe box containing the dress. Cut to a pan across another club, this one a disco where she scores: a man with a mustache and beard (Vesa Vierikko), as poker-faced as she is, asks her to dance and takes her home to his modern upper-middle-class flat. In the morning we see him leave her money on a table while she’s still asleep, just before he goes out. When she wakes up, she apparently doesn’t notice the money; she goes into the kitchen and writes him a note consisting of “Call me,” her phone number, and “Iris.” (This is when we first find out her name.)

The terseness or absence of dialogue, the gruff brutality of the parents, the heartlessness of the man, and the emotional nonexpressiveness of all four characters evoke the world of Bresson, especially his consecutive harsh rural fables of the 60s, Au hasard Balthazar and Mouchette. Though Kaurismaki’s style is usually less radical than Bresson’s (he doesn’t focus on the characters’ feet, for instance), his content — the designation of an abused heroine as someone to be monosyllabically fucked over by brutes — seems directly inspired by Bresson’s, though Kaurismaki doesn’t make any allowances for behavioral differences between impoverished French farmers and a well-to-do Helsinki hotshot, for instance. After Iris has suffered further callousness from her lover, finds herself pregnant, and winds up being treated even more miserably by him, her apparently deliberate miscarriage is depicted in an elliptical manner — she walks out of frame and a car screeches to a halt offscreen — that’s straight out of Bresson.

For all his powers of abstraction, Bresson is obviously interested in saying something about mankind in general and rural French society in particular in Au hasard Balthazar and Mouchette. By contrast, even though Kaurismaki has identified The Match Factory Girl as the final part of a trilogy (after Shadows in Paradise and Ariel) “dedicated to the memory of Finnish reality” — a look at that country’s working class, which he seems to regard as “what’s left of Finnish culture” — he defines that reality less through direct observation than by appropriating the attitudes of other filmmakers.

This brings us to the literary quotation that opens The Match Factory Girl: “They most likely died of cold and hunger far away there in the middle of the forest,” attributed to a character in Ivan Turgenev’s Countess Angelika. Kaurismaki’s gloss on the quotation, expressed during an interview, was “I feel that Turgenev’s description applies very well to the Finnish people, who seem meant not to be noticed.”

Clearly determined to be noticed, but knowing full well that Bresson’s uncompromising directness would land him in trouble, Kaurismaki adopts the postmodernist irony of Fassbinder and some of the hip irony of his pal Jim Jarmusch to ease the pain. He piles more and more misery onto Iris to make the movie comic, turning it into “playful” camp melodrama, cutesy S and M. And by God it works — the ending of The Match Factory Girl is the best thing in the whole picture.

Who cares if the ending invalidates most of what precedes it? Entertainment is supposed to be disposable, to make room for new entertainment; art just sits there like a big lump in your chest and won’t go away. Which would you pick if you made a Finnish movie that you wanted to get to the United States? (Even as entertainment, it’s taken three years for The Match Factory Girl to reach Chicago.)

Ultimately Iris’s awful plight is treated not so much as pathetic or tragic as hilarious. I won’t reveal how the story ends, but it’s an extreme and “satisfying” melodramatic finale deliberately inspiring camp laughter, not belief. It’s as if Kaurismaki were admitting he couldn’t believe in such an overdetermined story to begin with — or at least can’t respond to it, which in postmodernist terms may come to the same thing. So he’s opted for the irreverent pleasure of genre excess, which will slide him past what he can’t cope with on its own terms. Critic Matti Apunen puts it this way: “Kaurismaki walks the thin line between melodramatic over-emotionalism and subtle irony. His comical intentions are barely to be recognized: the stronger the tragedy, the stronger the comedy.” Or maybe he’s dealing in underemotionalism, unsubtle irony, and blatant comical intentions: the weaker the tragedy, the stronger the comedy. Whatever.