From the Chicago Reader (August 15, 1997). — J.R

In the Company of Men

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Neil LaBute

With Aaron Eckhart, Stacy Edwards, Matt Malloy, Michael Martin, Mark Rector, Chris Hayes, Jason Dixie, and Emily Cline.

In the weeks leading up to this year’s Cannes film festival it wasn’t clear whether the Iranian government would allow Abbas Kiarostami’s The Taste of Cherry, which it had banned in Iran because of its treatment of the theme of suicide, to be shown. The issue was settled before the festival started, but that didn’t stop Gilles Jacob, the festival director, from orchestrating the film’s arrival as if it were still a cliff-hanger — so that when it wound up sharing the top prize, the award was made to seem like a triumphant statement against government censorship of the arts.

I was delighted that Kiarostami’s film won, because I liked it better than anything else I saw at the festival — and it was the only time in my eight years of attending Cannes that my favorite had been so honored. But I felt queasy about the waves of self-congratulation this provoked among some members of the press (none, I should add, encouraged in any way by Kiarostami) — especially when it became apparent that the film would probably open in Iran after all. In all the euphoria no one was remarking on the much more subtle and prevalent presence in Cannes of capitalist censorship.

But then, ignoring — and therefore tolerating, protecting, and supporting — the numerous instances of capitalist censorship at Cannes is just business as usual. This kind of censorship usually involves suppressing or distorting relevant information when that will help sell a movie. It means, for instance, that even though Nick Cassavetes didn’t have final cut on She’s So Lovely, a feature derived from one of his father’s scripts, and was overruled on many particulars by his producers, we didn’t hear a word about this at the film’s press conference — nearly all of which was devoted to everyone saying how wonderful everyone else was to work with. It also means that even though Jean-Luc Godard’s entire eight-part Histoire(s) du cinema was to screen at the festival and didn’t, because Godard failed to complete the eighth part — he showed parts five and seven instead — there was no mention of these facts in any of the festival handouts or even at Godard’s press conference.

I could cite dozens of other examples, but I’ll focus on one that seems especially relevant to two of my other favorite films at Cannes, Atom Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter and Neil LaBute’s In the Company of Men: a refusal or reluctance in reviews to mention or discuss capitalism itself. I suppose this self-censorship may be unconscious because of the omnipresence of capitalism — discussing it may be as superfluous as discussing the air while describing a landscape. But not discussing capitalism makes for strangely skewed readings of both movies.

Put simply, In the Company of Men describes the effects of aggressive competition in business on masculinity and romance, and The Sweet Hereafter (which is likely to turn up here later this year), adapted by Egoyan from a Russell Banks novel, evokes the effects of aggressive competition in litigation on the functioning of a community. But in what I’ve read so far — and LaBute’s film has been written about a great deal since it premiered at Sundance back in January — neither film is examined too closely as a commentary on the way we live.

A serious movie about the way we live is inherently something of a provocation. But in his first feature writer-director LaBute has carried the provocation to the point where it’s virtually guaranteed to make us squirm. This isn’t to say that the bizarre plot of In the Company of Men is very believable apart from its own context, or that the thesis is a simpleminded polemic about capitalism turning us into savages. LaBute is much more interested in the why and how of the process by which competition in business affects personal and sexual behavior than he is in mounting an attack, though he’s clearly interested in rubbing our noses in some uncomfortable truths. A playwright who received a literary fellowship to study at London’s Royal Court Theatre when he was in graduate school, he cites Restoration comedy as the model for his screenplay, “where wealthy, blase characters do unspeakable things just because they feel like it.” (The plot also calls to mind the 18th-century novel Les liaisons dangereuses by Choderlos de Laclos, of whom Andre Gide said, “There is no doubt as to his being hand in glove with Satan.”) The film’s title, with its play on two meanings of the word “company,” is derived from the title of a David Mamet essay.

LaBute says that his original idea for the film was one line of dialogue, “Let’s hurt somebody,” which occurs at the end of the opening sequence. Chad (Aaron Eckhart) and Howard (Matt Malloy), young white-collar executives who went to college together ten years before, are sent by their home office to a branch office in a smaller city for six weeks. (In keeping with the film’s unobtrusive minimalism, the company, like both cities, remains unidentified.) Professionally as well as personally frustrated — by the promotion of younger colleagues ahead of them, by being exiled to the boondocks, and by having been dumped recently by their long-term girlfriends — they pepper their dialogue with resentments.

When we first encounter them in a “courtesy lounge” en route to their midwestern branch office, Chad — the slicker and handsomer of the two — hatches a monstrous plot designed to soothe their bruised egos and, as he puts it, “restore a little dignity to our lives”: find a young woman during their stay, shower her with attention and gifts that build up her romantic expectations, and then ditch her just before they leave. As Chad says, “Trust me, she’ll be reaching for the sleeping pills within a week, and we will laugh about this until we are very old men.” At once shocked, amused, and awed by the dimensions of such a scheme, Howard agrees to go along with it. Soon after their arrival — Howard, the weaker and less confident of the pair, proves to be the exec in charge at the branch office, with Chad working under him — Chad settles on an attractive deaf woman named Christine in their typing pool, and they both start dating her.

LaBute has said that his script has a five-act structure and “is a simple story: boys meet girl, boys crush girl, boys giggle,” but neither assertion is unequivocally true. (Both come from the press handout at Cannes, and it would be unrealistic to expect LaBute, for all his artistic lucidity, to be less guilty of business as usual in promoting his work than Godard or Nick Cassavetes.) After the prologue the film is actually broken up into seven parts, each identified by a separate chapter heading (“week one,” “week two,” and so on, to the concluding “weeks later”), accompanied by highly percussive bursts of free jazz, which are also heard behind the opening credits. (Consisting mainly of relentlessly pounding drums, this music also features a saxophone during its first and last three stretches emitting a wild, tortured series of honks and wails that parallel the characters’ emotional turmoil.) Properly speaking, only one of the boys, Chad, can be said to be giggling even figuratively by the end of the picture, and if anyone has been crushed at this point it’s certainly not Christine, who in many ways remains the strongest of the three characters. (I won’t reveal all the plot twists, but readers who plan to see the picture may prefer to check out here.)

The first time I saw In the Company of Men I tended to regard Howard as the more sensitive and humane and therefore the less detestable of the two antiheroes, but part of the film’s power as an act of provocation comes from undermining this easy assumption and even turning it on its head. Mousy, awkward, and uncertain throughout about his position as boss at the branch office (as Chad puts it, it’s his first time in charge), he’s far less cruel about Christine than Chad when speaking about her privately, and less dishonest about his responses to her in her presence — when he shows embarrassment it’s almost always genuine — which makes it easier for us to identify with him. But when it comes to action he’s a good deal less lucid about his intentions and arguably winds up inflicting even more damage. The competition between him and Chad is of course just as operative throughout the film as the competition between the two of them and their coworkers, and the role of the grudge match between them in their daily work is obviously reflected in their plot to ensnare Christine — but only Chad has the lucidity to know what he’s doing and why every step of the way. Thanks to this difference, both Christine and Howard wind up being victimized by Chad. But Christine is strong enough to recover and move on; by the end Howard is practically a basket case.

Chad evokes some of the reptilian cunning and vanity of Erich von Stroheim’s lead roles in his early pictures Blind Husbands and Foolish Wives; as the ads in the 1920s said, Stroheim’s “the man you love to hate.” In The Company of Men invites us to relish Chad’s Machiavellian single-mindedness even as it slams us against his derisive cruelty. This cruelty is most apparent whenever he speaks to Howard about Christine’s choked form of speech (very persuasively handled by the nondeaf Stacy Edwards) — cracking an endless stream of abusive jokes that sound like the purest form of neoconservative humor. By contrast, Howard comes across as humorless, anal retentive (three scenes plant him inside a men’s room), a mama’s boy, and a bit of a worm, though it is he who controls our viewpoint on most of the action. By virtue of our uncertainties about him, he’s the key to our uneasy relation to the material; our ambivalences may not be the same as his, but they guide us into the story.

Here’s where the film’s commentary about capitalism and its capacity to bait us is most explicit. Howard, who’s much less successful than Chad in snowing Christine and winning her affection, uses his authority as boss to maneuver himself into a position where he can take her to a fancy restaurant over the Fourth of July weekend, meanwhile sending Chad off on a trip and sprucing up the expensive ring his former girlfriend returned to him so he can present it to Christine at an opportune moment.

Sandwiched between Howard’s visit to a jeweler and his date with Christine is a pivotal scene: Just before Chad leaves on his trip, we see him sitting at Howard’s desk, dressing down a young black intern, giving him a “fatherly” lecture about his behavior at work. In some ways this is the film’s craftiest scene, because it’s the most outrageous. It builds toward its biggest outrage — Chad’s insistence that the intern drop his pants and show him his balls — in such a way that we can’t tell when the threshold between the reasonable and the unreasonable is crossed. (In confronting the audience with the monstrousness of what it has already accepted, it resembles the last act of Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming.) Munching on a sandwich — as Howard was doing with Chad in a previous scene — Chad says, “Let’s see ’em, then, these clankers of yours. Let’s see what you got….Listen, you got a kind of pair that men are carrying around, you practically wear ’em on your sleeve. That’s what business is all about — who’s sporting the nastiest sack of venom and who’s willing to use it.” After the intern sheepishly drops his trousers, Chad completes the ritual humiliation by asking him to fetch a cup of coffee, and we cut directly from this scene to Howard with Christine at the restaurant.

Livid at being spurned by Christine, because by now she’s fallen in love with Chad, Howard spills the beans to her about their “game.” But because his own vanity has been wounded, he can’t be pure about the gesture; fruitlessly hoping to gain her affection by exposing Chad’s contempt for her, he can only humiliate himself. By forcing us to consider the messiness of Howard’s behavior as closer to our own impulses, LaBute implicity raises the issue of our own complicity in the uglier aspects of capitalism that inform our own everyday emotional confusions. The sad fact is that Chad comes across as a self-perpetuating, impregnable myth, for better and for worse; Howard is a human being and a fumbler.

There are still at least a couple more turns of the screw before we reach the end of this nasty parable about power. But the strength of LaBute’s conception every step of the way is in forcing the issue of where we belong in this picture — with Chad, with Howard, or with Christine. Wherever we choose to settle, however provisionally, isn’t going to be comfortable, but our discomfort can teach us something about the way we live.

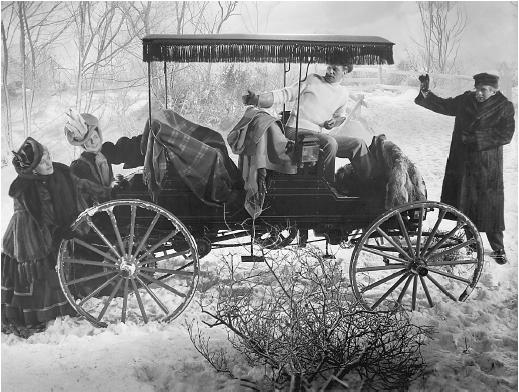

Chad delivers the only line in the movie that contains an overt movie reference; hearing Howard say that he went for a drive with Christine on the Fourth of July, he responds, “A drive? That’s nice — quaint. A little Magnificent Ambersons thing going on, or what?” In comparison with the film buffery usually displayed by filmmakers, this comes across as a freakish non sequitur — a stupefying curveball. Yet who’s to say that a creep can’t make a hip allusion? After all, Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons does offer a conundrum about the mess capitalism can make of our lives and the confusing emotional alliances we make in relation to this mess. In that film it’s the gentle and sweet-tempered inventor, Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotten), who ushers in the barbarism and filth of the automobile, and the vain and odious aristocrat, George Amberson Minafer (Tim Holt) — the one who takes the heroine for a drive in a horse and buggy — who’s ground into dust.