Written for the Library of America’s web site The Moviegoer. The version published there on May 3, 2017 differs somewhat from the original version posted here, especially the ending. — J.R.

No less than seven features to date have been based on works by Philip Roth, and three of these have been directed by first-timers, all of whom previously made their cinematic mark in other professional capacities. Ernest Lehman (1915-2005) had a long and distinguished screenwriting career before directing his own adaptation of Portnoy’s Complaint in 1972, and Ewan McGregor acted in over four dozen features before directing American Pastoral 44 years later. James Schamus, a film professor at Columbia University, had over fifty producing credits — plus writing and producing credits on all but three of Ang Lee’s features — before he added direction to his producing and writing on Indignation. This has yielded what Stephen Holden in the New York Times has called “easily the best film made of a Roth novel, which is saying a lot.”

Schamus’s dexterity in navigating both commercial film production and academia has served him well on this project, enabling him to honor his source while rendering it both accessible and personal. Read more

I’d like to beat the drum a little for a terrific new book just published by University of California Press, Catherine Benamou’s It’s All True: Orson Welles’s Pan-American Odyssey, which is far and away the definitive book on It’s All True, Welles’s doomed documentary project about Latin America in the 1940s. Maybe the fact that the same publisher is bringing out a book of mine about Welles in a couple of months gives me a special interest in the subject; I should also note that Benamou, who’s been working on her book for well over two decades, is an old friend. (She also arranged recently for the purchase of two major Welles collections by the University of Michigan, which are going by the name “Everybody’s Orson Welles.” I was privileged to be the first visitor to this mountain of material in Ann Arbor last summer, which is where I collected the stills used on my own book jacket.)

Some readers may be put off a bit by Catherine’s academic language, but the fact remains that so much fresh and even startling information is available here—information that corrects countless myths—that if you care about Welles at all, you can’t afford to ignore this book.

Read more

This originally appeared in the twelfth issue of Camera Obscura (Summer 1984). I’m delighted that a DVD of Sally Potter’s overlooked, neglected, and scandalously undervalued masterpiece is finally available, from the British Film Institute. I wrote a short essay for the accompanying booklet. –J.R.

The Gold Diggers: A Preview

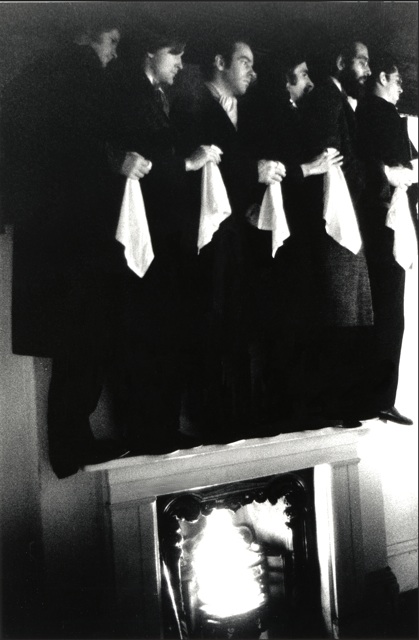

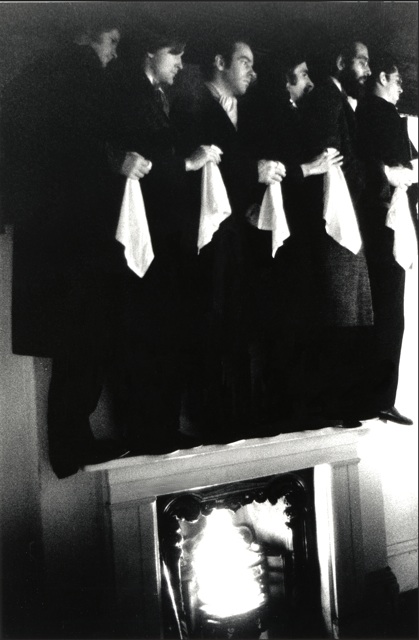

Sally Potter’s much heralded British Film Institute production has been encountering a lot of resistance since it premiered at the London Film Festival late last year. When I saw it at the Rotterdam Film Festival in early February, its presence even there was regrettably nominal: screened only once, and in the Market rather than as a festival selection, it was received rather coolly, and many of the critics present left well before the end. Finding the film visually stunning, witty, and pleasurably inventive throughout, I can only speculate about the reasons for the extreme antipathy of my colleagues.

Historically, The Gold Diggers demands to be regarded as something of a proud anomaly. While it contains many familiar echoes of avant-garde performance art (including music, dance, and theater), its only recognizable antecedent in the English avant-garde film tradition appears to be Potter’s own previous Thriller. (An English language film which is international in conception as well as execution, it is marginal in the best and most potent sense of that term.) Read more