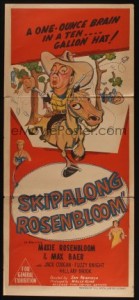

I devoted almost an entire page in my first book, a memoir, to this unsung obscurity, a low-budget comedy western that I saw in Florence, Alabama with my brother Alvin on November 14 or 15, 1951, when I was eight and he was six, on a double bill with Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Man from Planet X. I can very nearly classify this viewing as my first cinematic encounter with the avant-garde, by which I mean something akin to what J. Hoberman calls Vulgar Modernism — eight months after what might have been my first non-cinematic encounter with the avant-garde when I attended a Spike Jones concert one Sunday afternoon at the Sheffield Community Center. Bear in mind that I saw Skipalong Rosenbloom a full year before the first issue of Mad (the comic book) appeared and almost two years before I bought my first issue (no. 6, August-September 1953); this was also a full year before I saw Frank Tashlin’s Son of Paleface. It’s quite possible, of course, that I’d already seen one of Tex Avery’s cartoons by then, but if I had, this fact couldn’t be traced by the same methods of research that I employed in my memoir, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, which mainly involved combing back issues of the local Florence newspaper on microfilm for movie ads. Read more

This appeared originally in Senses of Cinema, issue 17, November 2001. The book it appears in has subsequently reappeared in an expanded second edition. — J.R.

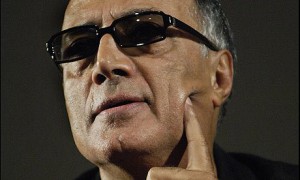

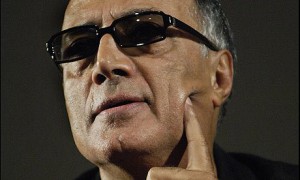

The following is an extract from Abbas Kiarostami by Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa and Jonathan Rosenbaum (University of Illinois Press, 2003) – one of the initial books in a series edited by James Naremore that is devoted to neglected contemporary filmmakers. Abbas Kiarostami contains separate essays by Rosenbaum and Saeed-Vafa followed first by this dialogue, then by an extended interview with Kiarostami conducted by both authors.

***

September 3, 2001, Chicago

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM: You were the one who originally had the idea of proposing that we do this book together. And maybe we should both consider why we thought it was a good idea.

MEHRNAZ SAEED-VAFA: Basically, as far as I remember, we had a lot of interesting dialogues about Iranian cinema and Kiarostami, and I thought it would be a great idea to put our effort into a book. We started our dialogue in 1992, at a time when Kiarostami was still was getting discovered in France, but unknown in the United States. And I respected you highly as a critic and I knew that you were respected among other readers outside the United States as well as inside. Read more

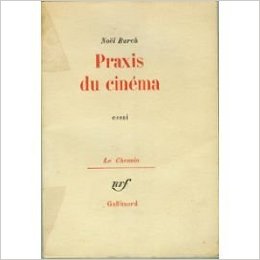

For its 100th issue (Winter 2o16), the French quarterly Trafic asked its contributors to select a particular book that had a formative influence on him or her. Here is my contribution. — J.R.

I still have the original Gallimard edition, probably the most tattered and thumbed-through French book that I own, published in 1969, the same year that I moved to Paris from New York — the title missing the article (Une Praxis du cinéma) that is now found on the 1986 edition. I can even recall purchasing this book at Le Minotaure, a Surrealist bookstore on Rue des Beaux Arts, a short distance from my rented flat on Rue Mazarine, and the ridiculous advertising slip (against which Burch rightly protested), “Contre toute théorie,” that enclosed it.

By this time, I’d already read — or at least tried to read, back in New York — earlier drafts of some of the chapters when they had appeared in Cahiers du Cinéma, and may have also read Godard’s praise of one of those chapters in one of his interviews. Due to a crippling disability in learning languages, much of which I still suffer from today, I had to read those chapters with the aid of a French-English dictionary, even though Burch’s French—the French of an American émigré — was far easier to follow than the French of Roland Barthes in Le plaisir du texte, published four years later, which eventually became my other key French text of this period. Read more