Written for Frank Tashlin, edited by Roger Garcia (Éditions du Festival international du film de Locarno in collaboration with the British Film Institute [London]/Editions Yellow Now [Crisnée, Belgium], 1994). -– J.R.

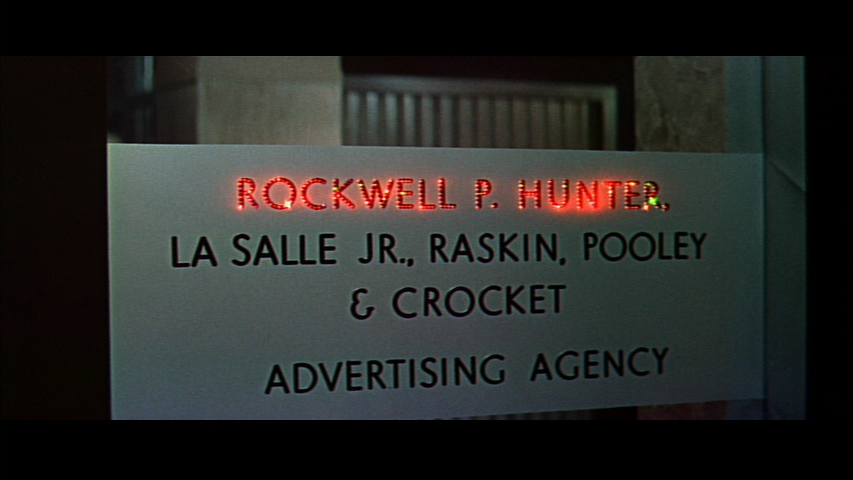

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?

Clearly Tashlin’s most avant-garde feature, and probably his most political, thus his most misunderstood. Retaining the title, Jayne Mansfield, and advertising from George Axelrod’s Broadway play, but reportedly little else, Tashlin mounts a thoughtful and multifaceted polemic against the success ethic itself. (A key line: “Success will fit you like a shroud.”) The consequences are dazzling for his art but disastrous for his career. Made at Fox on the heels of The Girl Can’t Help It, the film provides a textbook illustration of George S. Kaufman’s maxim, “satire is what closes in New Haven.” Fortunately, before the balance sheets are counted, 50s America receives one of its two most devastating caricatures on film; the other is Chaplin’s A King in New York, made the same year. Paraphrasing Rossellini, both are the films of free men; fully anticipating Godard’s journalistic directive that you can – and must – place everything in a film, both filmmakers hit on nightmarishly topical New York dystopias set in the present, where, thanks to TV and advertising (rightly perceived as synonymous), the divisions between public and private are now fully obliterated.

“One can approve vulgarity in theory as a comment on vulgarity,” wrote Andrew Sarris, “but in practice all vulgarity is inseparable. . . . To ridicule Jayne Mansfield’s enormous bust in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? may be construed as satire, but to ridicule Betsy Drake’s small bust in the same film is simply unabashed vulgarity.”‘ Neither bust is in fact ridiculed — it’s the breast worship engulfing and oppressing both women that Tashlin mocks — but much as Chaplin’s treatment of plastic surgery (rather than plastic surgery itself) was declared tasteless, Tashlin’s most daring forms of irreverence were sometimes mistaken for exploitation. (As Diane Johnson notes, “In the 1950s there were fewer words for oppression.”) And given the intolerant climate of the period, which made Tashlin a disreputable blood brother of Spike Jones and Harvey Kurtzman, some of his other satirical targets were equally sacred: to start out by devaluing the Fox logo was almost like spitting on the flag. (In order to signal his necessary implication in the same ad culture he derides, and perhaps also to placate his skeptical bosses, Tashlin takes care to inject blatant plugs for no less than seven recent or upcoming Fox releases, as well as several Fox actors.)

This lighthearted jeremiad correctly and prophetically perceives that advertising not merely competes with contemporary culture; it is contemporary culture. A corollary perception, which this picture spells out in numerous ways: that television, far from facilitating communication and social interaction, effectively replaces it. Significantly, when the title hero (Tony Randall), an ad writer, wants to discover what happened to his niece, or even wishes to know what Rita Marlowe (Jayne Mansfield) is saying downstairs, directly below his flat, he turns on his TV set.

No other CinemaScope film of the 50s is so completely haunted by the specter of television. Commercials start even during the credits, an entr’acte is introduced by Randall for the sake of TV fans in withdrawal (the screen size obligingly shrinks and shifts to black and white), and the plot’s absurdist climax occurs when, on a TV special, Groucho Marx in his TV quiz-show persona — an almost literal deus ex machina — makes a surprise guest appearance, turning out to be Marlowe’s long-lost love. When the smoke clears, the hero — at this point the president of his ad agency — has reverted to blissful ordinariness and become a chicken farmer.

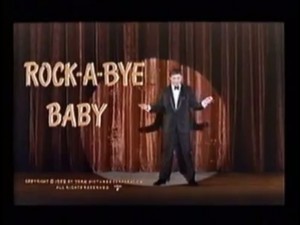

Rock-a-Bye Baby

If this is as much of a remake of The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek -– apart from a few stray gags and ideas — as some critics imply, it’s significant that for Brian Henderson, Jerry Lewis takes over Eddie Bracken’s role, while for Andrew Sarris, he replaces Betty Hutton. Either way, this is the first Lewis-without-Martin feature directed by Tashlin, and its characteristic narrative discontinuity at the beginning forms an interesting auteurist continuity with Tashlin’s previous feature, made without Lewis for a different studio. Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? ends with the characters suddenly removed from their naturalistic environment and placed in front of a stage curtain; Rock-a-Bye Baby begins behind its credits with Lewis in front of a stage curtain, assuming his brassy nightclub persona as he belts out a version of the film’s theme song -– then continues as he moves through a series of studio soundstage locations. Confusingly, the ensuing story’s show-biz character is not Lewis but Marilyn Maxwell, and the opening scene, set on a studio lot, involves Maxwell but not Lewis.

Stranger still, Lewis’s character in the film, Clayton Poole – a childhood sweetheart and still-devoted fan of Maxwell, working as a TV repairman in the small Indiana town where they both grew up — is later shown humming the same theme song while he pins up diapers on a clothesline. This implies a continuity of discourse beyond the discontinuity of characters and settings that seems entirely characteristic of Tashlin’s modernist approach to storytelling. (Comparing Tashlin with both Sturges and Godard, Henderson has some fascinating observations to make about narrative ellipsis in this film.) This was Lewis’s third feature without Martin, made at a time when he was still defining his new persona — which probably accounts for the discrepancy between the onstage Lewis and Lewis-as-Poole, as well as the somewhat contradictory treatment of Poole’s libido. (When Maxwell rhetorically asks Poole, “How can I ask you to be the father of my children?” his response is adolescent terror, a series of hysterical double-takes; yet much later, in the same setting, when he suddenly recalls he’s married to Maxwell’s kid sister — Connie Stevens — he cackles with maniacal glee over the prospect of their having sex.)

This is clearly a film whose authorship is shared by Tashlin and Lewis, the latter serving as producer (for the second time in his career, after The Delicate Delinquent). Robert Benayoun also credits Lewis as cowriter and suggests that while the film’s satiric aspects can easily be attributed to Tashlin (“notably whatever involves Hollywood and The Virgin of the Nile, as well as the sublime character of Miss Bessie, the perpetual victim of TV commercials”), the character of Poole and his ambition to become a “perfect mother” seem more the work of Lewis, as do other personal touches (such as Lewis’s son Gary playing Poole as a child).

In other words, it’s a collaboration. While one might further guess that most of the film’s many references to TV come from Tashlin, the most extended sequence relating to TV has Lewis behind the shell of an empty TV set running through an anthology of past and future Lewis impersonations — a country-western cowboy, an “Uncle Raul” comprising an early draft of Nutty Professor Julius Kelp, a version of Eddie Mayehoff harking back to That’s My Boy, an Italian opera singer, and the buck-toothed Japanese that would sustain him over subsequent decades. By contrast, the brilliant early sequence with a runaway fire hose seems purest Tashlin, all the way down to the Tashlinesque white poodle.