Written shortly after the Rotterdam Film Festival in February 2004 for Cinema Scope. It’s too bad that it hasn’t been possible for anyone (except for Ray Carney and his students, apparently) to see the first version of Shadows again since that festival, apart from the three short clips that Carney posted here. (The reasons for this have been discussed by Carney on his web site, but not, alas, by Gena Rowlands, Al Ruban, and/or the late Seymour Cassel in any comparable public forum, as far as I know. I should add that all the photographs here, apart from production stills, are from the second version.) — J.R.

In many respects, the most interesting movie I saw at the Rotterdam Film Festival last month was neither new nor a Golden Oldie, at least in any ordinary sense of either term, but a work that had been considered lost for almost half a century —- the original version of Shadows, John Cassavetes’ first feature, shot in the spring of 1957. Extensively reshot by Cassavetes two years later and re-edited into the film as we now know it, this shorter and rougher version was heralded by Jonas Mekas in 1960 as not only superior to the second, but a major aesthetic breakthrough, and we’ve had to wait 40-odd years to test the merits of his claim.

But can we test it? Perhaps the most valuable history lesson afforded by seeing the first version in 2004 is that calling Mekas either right or wrong in his judgment is much less easy than it sounds, because the ground has meanwhile shifted under our feet. The problem for me isn’t just that the second version is one of the films I cherish the most —- and has been ever since I discovered and then kept returning to it at 18, over one spring break from boarding school during its New York commercial run. This means that I’m likely to resist Mekas’ preference for the first version for the same reason that he resisted my preference for the second — because we both responded to love at first sight, and when it comes to primal experiences of this kind, first impressions are impossible to overcome. Even more importantly, the whole configuration of cinema as we know it has been radically altered in the interim, in more ways than we can begin to count. Obviously part of what Jonas was responding to was a gem in the rough, because one can’t avoid the fact —- and Jonas certainly didn’t avoid it, clearly regarding the film as a sort of accidental masterpiece —- that the initial version is far more riddled with technical flaws than the second: bad lip sync, klutzy exposition, an overall sense of sprawl in spite of all the dogged obeisance to certain narrative conventions. Yet looking at the same film in 2004, a gem in the rough is also what I just saw, even though the gem in my case was my memory of the second version. Therefore, as illogical as this sounds, the first version can be read by me only as a shadow of the second. Maybe this is because we invariably impose our own time frames on those of film history whether we want to do this or not.

Another history lesson afforded by the first Shadows that stems from this incongruity is how unreliable memories tend to be, and how often film history tends to be a matter of copying and recopying the same errors ad infinitum. Virtually every account of the first version that we have in print gives the running time as 60 minutes (versus the second version’s 81), but it turns out to be 18 minutes longer than that, only three minutes less than the “longer” version. Furthermore, Mekas gave the impression that the original was more nonnarrative than the second version, but in fact it has a more conventional narrative line with more conventional continuity and crosscutting much of the time, even though other parts might be said to dawdle when it comes to advancing the story proper (such as details of shops and various kinds of street activity when Ben Carruthers is walking, with or without his friends Dennis and Tom). On the other hand, it might be argued that part of what undoubtedly looked transgressive half a century ago looks classical now, while certain other elements that no one appears to have noticed at the time — most notably Charles Mingus’s original jazz score — now look truly experimental.

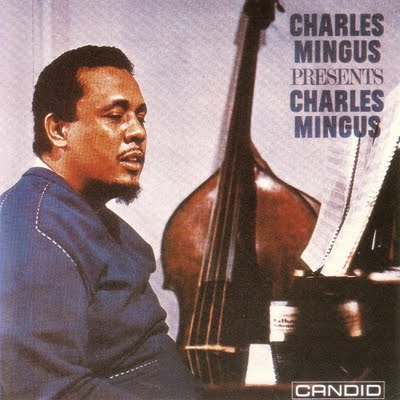

Part of what makes this score experimental is the way it periodically editorializes on the characters and action, so that a trumpet with a mute (probably Clarence Shaw) replacing Tony Ray’s voice in a phone conversation becomes a mockery of both the character and his pretensions, and a Jimmy Knepper trombone solo playing over a subsequent appearance of the same character offers a less aggressive and less obvious example of the same procedure. (This recalls the musical “conversations” between Mingus and Eric Dolphy that were carried out later, one striking sample of which can be heard on the superb 1960 Candid album Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus, culminating in an “argument” between the former’s stern bass and the latter’s squawking bass clarinet.) Insofar as this technique appears to periodically take over the jobs of the actors and director, thus pointing up certain weaknesses in the dramaturgy, it’s easy to see why Cassavetes eliminated it in the second version — just as he chose to eliminate a striking musical passage used over the scene of Bennie, Dennis (Dennis Savalas), and Tom (Tom Allen) recovering from a harsh alley beating, with the sound of Mingus and some of his fellow musicians disconcertingly shouting out a gospel tune about “leaning on Jesus”. And another experimental aspect is the film offering a highly fragmented and disjunctive series of diverse musical groupings and settings —- most likely as an unwitting consequence of the editing, so it probably doesn’t reflect any conscious strategy on the part of either Cassavetes or Mingus.

Cassavetes specialist Ray Carney, who miraculously found the lost print after many years of obsessively hunting for it, had the fragile (though infrequently shown) 16-millimeter print transferred to DigiBeta video for the two Rotterdam screenings, and I’m sorry that I was able to make it to only one of these, because it’s not at all clear at this point when or even if the film will become visible again. Ideally we can hope that both versions might eventually turn up on the same DVD — but of course we live in a far from ideal universe where it’s far from easy to see my other favorite Cassavetes films, Love Streams, so this may only be wishful thinking. (The rights issues with the first Shadows are bound to be thorny, especially if one considers the use of two Frank Sinatra cuts, “My Funny Valentine” and “Like Someone in Love,” during separate scenes of Lelia dancing.) According to Carney, the film wound up in a lost and found department of the New York subway —- though how it got there is anyone’s guess —- where it wound up being auctioned off with diverse other stray articles, and purchased by a man who had no particular interest in film or knowledge about Cassavetes, who apparently examined the film only to discover whether it might be porn or not. (For portions of the remaining saga of how it was found, see Carney’s web site, www.cassavetes.com, which also reproduces an excerpt from Mekas’ January 27, 1960 Village Voice column defending this version over its better-known successor.)

No less fascinating are scenes in both versions that are substantially the same (altered, say, only by a better lip sync or slightly different line reading) but which wind up meaning something quite different. The most remarkable instance of this kind of play with meaning can be found in the two versions of Jacques Rivette’s Out 1, where Rivette consciously sought in many cases to have the same shots have radically different meanings; here one suspects that these variations tend to crop up more accidentally, and often as the results of other changes (such as the music), but they are fascinating none the less. One of the final scenes in the release version, after Benny, Dennis, and Tom get their harsh beating for fooling around with some other guys’ dates, shows Benny remarking to his friends, “You want me to be corny and say I’ve learned a lesson, okay, I’ve learned a lesson,” and implicitly vowing to change his ways. But in the original version, the same scene occurs much earlier in the film, followed by Benny, Dennis, and Tom behaving precisely the same way as before, so the meaning of this speech is almost reversed: what gives some sort of closure in the second version, complete with a tacked-on moral that lends an unexpected dignity and note of self-recognition to Benny’s otherwise lost character, is subsequently made to seem hollow and almost meaningless in the original.

Considering how much mileage is gotten out of Lelia (Lelia Goldoni) losing her virginity in the release version, it’s a bit of a shock to discover that she doesn’t have sex with Tony at all in the first version, but merely spends the evening talking to him. Once again, there is some reason to suspect that this difference in plot came about through some form of incompetence, because Carney reports that there were so many retakes of Lelia and Tony’s “love scene” in the first version that Goldini’s lips started bleeding, even though none of these takes were finally used. So might we conclude that the seduction never happened in the first version only because Cassavetes wasn’t happy with the results when it did?

More often, the weaknesses in the first version aren’t so much omissions as belt-and-suspenders overstatements and reinforcements —- scenes offering cumbersome explanations or rationalizations of what we’ve just seen that were sensibly stripped away in the upgraded 1959 version. There’s even an awkwardly placed remark to Bennie by either Dennis or Tom in the earlier version after a visit to the flat he shares with Hugh (Hugh Hurd) and Lelia: “I can’t figure it out. Hughie -— he’s so dark to be your brother!” (The fact that Goldini was a white actress playing a black character would only much later be seen as politically incorrect and illegitimate by academic critic David E. James, indicating to me a loss rather than a gain; back in 1961 the performance seemed brave, adventurous, and even beautiful.)

Carney has maintained that Shadows is a minor film next to Faces, but I would guess that this is at least partially because he identifies more with the middle-class milieu of the latter film than with the bohemian world of Shadows — the reverse of my own priorities. But as Nicole Brenez recently and sensibly pointed out to me, both films are major works, so ranking them in this fashion is fairly pointless. The main thing we have to be grateful for is a modest yet crucial addition to the Cassavetes canon — not simply a “first draft” of something we already know but a whiff of the chaos and the raw passion from which it sprang, which is surely the beauty that Mekas found and defended.