One ironic footnote to the following article, which ran in the March 6, 1992 issue of the Chicago Reader, is that it was itself subjected to a kind of “soft censorship”. Specifically, my editors refused to allow me to allude to having known Chevy Chase personally as a classmate at Bard College during the mid-1960s, which I thought gave some additional weight to some of my reflections about the personal nature of Memoirs of an Invisible Man. (Since I no longer have access to my initial draft, I can’t spell this out here in any detail, except to note that Chase’s jazz piano now figures in the final draft only as a parenthetical detail.) Not only did Chevy and I share a course or two, but we also bonded in various ways through our mutual interest in jazz: in a few student jam sessions, I played piano while Chevy played drums (although he also played some piano even then), and we collaborated at one point with Blythe Danner (another Bard classmate, and a jazz vocalist at the time) on a successful project to bring Bill Evans and his trio to campus to give a concert. —J.R.

THE WAGES OF FEAR

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot

Written by Clouzot and Jerome Geronimi

With Yves Montand, Charles Vanel, Vera Clouzot, Folco Lulli, Peter Van Eyck, and William Tubbs.

MEMOIRS OF AN INVISIBLE MAN

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by John Carpenter

Written by Robert Collector, Dana Olsen, and William Goldman

With Chevy Chase, Daryl Hannah, Sam Neill, Michael McKean, Stephen Tobolowsky, and Jim Norton.

We all know what hard censorship is. Tautologically speaking, it’s what censors do — government bureaucrats in repressive regimes, or prudes and religious ideologues who work through pressure groups in democracies. But maybe we’re leaving something out. When a movie is cut for what are called business reasons — sometimes based on the responses of preview audiences — we don’t generally call that censorship. When a magazine or newspaper kills a story because advertisers, investors, or owners might object, a few might call it censorship, but most of us never even hear about it; business looking after its own interests is usually protected from the scorn reserved for governments practicing repression.

But what about totalitarian governments that regard themselves as businesses? Earlier this year in Rotterdam I saw a couple of good Chinese films that are completely banned in mainland China — no reasons given, which is standard procedure in that country. While it was assumed that these movies had somehow been sneaked out of China, the evidence suggests that Chinese authorities were well aware that they were being shown abroad and didn’t object because they could generate useful income for the Chinese government — which had helped to finance them in the first place. This double standard is reminiscent of the policy followed by United Artists in the mid-70s when it hemmed and hawed about letting Pier Paolo Pasolini’s shocking Salò be seen in New York City but had no compunctions about showing it in Puerto Rico (where it in fact premiered).

For the purposes of this discussion, let’s call censorship for business reasons “soft.” It was soft censorship that was responsible for Henri-Georges Clouzot’s suspense classic The Wages of Fear being severely cut before it opened in New York in 1955, even though it had won the grand prizes at the Cannes and Berlin film festivals two years earlier. It may even be soft censorship that is responsible for the confusion about whether the “restored” version is in fact complete. And in a different context, it was soft censorship that prevented the talented director of Memoirs of an Invisible Man, John Carpenter, from having any control over the movie’s editing. Ironically the film’s theme of invisibility points to the consequences of still another form of soft censorship.

We like to think we know what we’re getting when we go to the movies — that the credits are accurate, that the version we’re seeing (if it’s an older film) is the original one. Of course we can’t expect every theater to do what Studio-Action Lafayette does in Paris, which is to post the condition of every print it shows (good, fair, or poor) on the box office window, but we’d rather not be hoodwinked. Unfortunately, thanks to soft censorship we’re hoodwinked when it comes to the credits of many new movies — especially concerning final creative control — and often fooled or at least confused when it comes to most “restorations.”

Kino International proudly describes the version of The Wages of Fear opening today at the Music Box as “complete” and “restored,” with a running time of 148 minutes, a full 43 minutes longer than the version that opened at the Paris Theatre in New York in 1955. But, to cite one of those glitches that drive people like me around the bend, authoritative and usually reliable references ranging from Leonard Maltin’s TV Movies to Georges Sadoul’s Dictionnaire des films to Pauline Kael’s 5001 Nights at the Movies list the original running time as 156 minutes. Furthermore, a detailed article excerpted in Kino’s press materials states that only 24 minutes were excised for the original U.S. opening. So who’s holding out on us? Has Kino misplaced, overlooked, or suppressed eight minutes, or have Maltin, Sadoul, and Kael all copied their information from the same erroneous source? Does the original 156-minute version no longer exist? Or did no such version ever exist in the first place? And what about the 19-minute discrepancy between the lengths of the cuts described in Kino’s own handout?

Despite the cuts The Wages of Fear was an enormous hit in the U.S. and it’s not hard to understand why. In its original form an action picture with some philosophical and social pretensions, Clouzot’s grim thriller had been basically stripped down to its action components, which are among the most gripping to be found anywhere in movies. As it happens, I liked the movie when I saw it in its reduced (and censored) form as a teenager, despite its changed ending, but I like it even more now in its complete (?) form. Its somewhat dated macho and existentialist elements notwithstanding, the film’s pile-driving persistence over two and a half hours commands a certain numbed respect.

Describing Clouzot as one of the “water buffaloes of film art” (along with George Stevens, Billy Wilder, and Vittorio De Sica), Manny Farber argued in 1957 that The Wages of Fear, his “most successful work,” is “a wholesale steal of the mean physicality and acrid highway inventions in such Walsh-Wellman films as They Drive by Night.” He had a point — the film shows a mastery of the gritty moods of American B-films — but he might have added how Clouzot borrows from Italian neorealism (including De Sica) and Luis Buñuel’s Los olvidados. This isn’t a matter of specific film references — a practice that was to take root in the French cinema a few years later, with the advent of New Wave directors like Godard, Rivette, and Truffaut — but rather evidence of Clouzot’s deft assimilation of influences.

In the final analysis, this is very much Clouzot’s own movie, based on a best-selling novel by Georges Arnaud — which French critics say he improved upon — as well as Clouzot’s own experiences in Brazil in the early 50s. The entire film is set in an unidentified part of Central America and persuasively filmed in the Camargue, in the south of France. The mood of cosmic hopelessness hanging over the whole picture is very much a reflection of the French intellectual climate; while this mood is far from the only aesthetic manifestation of existentialism in the early 50s — check out The Story of Three Loves, an arty MGM sketch film in color released the same year, for a radically different example — the macho French “attitude” on display here is certainly more emblematic of how that era is remembered today.

From the opening shot — of a half-naked boy playing with insects — it’s a mean vision of a mean world, and Clouzot invites us to luxuriate in its vileness. We find ourselves in a muddy, squalid village dominated by an oil well. On a sunbaked porch in front of a saloon, sweaty, idle men trapped in town by the scarcity of work amuse themselves by throwing rocks at dogs, spraying themselves with soda water, and spitting on the floor. Many of the men are European — we hear French, English, and German spoken as well as Spanish — and all of them are trying to devise ways of escaping from this hellhole.

Gradually we get to know some of them — including Mario (Yves Montand), a cocky Frenchman and the primary focus of Linda (Vera Clouzot), who works at the saloon; Luigi (Folco Lulli), Mario’s rotund Italian roommate who is destroying his lungs by working as a bricklayer; and Bimba (Peter Van Eyck), a taciturn and solitary Dutchman. When another, older Frenchman named Jo (Charles Vanel) arrives in the village, clearly in flight from the law, he and Mario strike up an instant bond, which entails a snobbish disdain for everyone else in sight. (Linda and Luigi are both dispatched into the role of spurned lover.) Upon their meeting, the two Parisians make a point of taking a taxi to the saloon — barely one unpaved block away — to make the right “impression,” and Clouzot’s dry and amused treatment of such social rituals dominates the first section of the film.

The town is run by the greedy American Southern Oil Company (“Wherever there’s oil, there’s Americans”), presided over by a cynical boss called O’Brien (William Tubbs). When an oil well explodes 300 miles away, resulting in several injuries and deaths, O’Brien decides to send nitroglycerine from the village to extinguish the fire. He advertises for four men to drive two trucks carrying the explosives across the primitive mountain roads, offering $2,000 each if they survive the trip. (Only one truckload is necessary, but he sends a backup because of the likelihood that at least one of them will explode en route.) After a series of drivers are tested, Mario, Jo, Luigi, and Bimba take off in the dead of night.

From this point on, the movie is an adroit suspense thriller — the bulk of what American audiences saw in 1955. An important subplot concerning Mario and Jo, who travel together in one of the two trucks, was drastically trimmed in the original U.S. version. Although Jo apparently commits a murder in order to be hired as one of the drivers — it’s hinted at but never spelled out — he blows his cool and succumbs to fear very early on, which seriously impairs his relationship with Mario (and incidentally accounts for the movie’s title). What is essentially a love story between two men, though evident in every version of the film, was largely obscured in the first censored version. (Unless I missed something, however, there’s still no allusion in the current version — at least in the subtitles — to Mario’s dislike of homosexuals, which reportedly figures in the original.)

While it could be argued that The Wages of Fear was censored to suppress the film’s homoeroticism and anti-Americanism, it also seems quite possible that the original distributor simply wanted to pack in more shows per day, or not scare away the action crowd with the movie’s length. Whatever the reasons, the cuts deleted everything from glimpses of a little boy’s genitals to an entire tragic subplot involving a young Italian who hopes to be selected as one of the drivers, and they concealed elements of characterization, atmosphere, and dramatic continuity. Even the film’s explicit philosophical underpinnings are muddled by the removal of much of Jo’s death scene, including references to the “nothingness” in a vacant lot on the rue Galande, Jo’s street in Paris.

In conclusion, it shouldn’t be assumed that soft censorship of Clouzot began with the first American release of The Wages of Fear. A much more serious case of it occurred when he directed the very popular Le corbeau (The Raven) for a Nazi production company during the French Occupation in 1943. A creepy noir mystery about poison-pen letters in a provincial village, it wasn’t a collaborationist work in any thematic way. But perhaps because its misanthropic and antibourgeois nihilism was regarded as demoralizing by the Resistance, it was labeled as collaborationist by postwar French governmental authorities, who not only banned it but punished most of the people involved in its production, barring both Clouzot and his screenwriter from work in the French film industry for two years.

***

Memoirs of an Invisible Man is a rather melancholy comedy-fantasy and action picture that for some time has been a pet project of its star, and among the personal traces of Chevy Chase in the conception of this project is, not unimportantly, a certain ambivalence about his own image.

Chase plays a San Francisco stock analyst who is rendered invisible through an industrial accident, and according to the conventions of light comedy and fantasy, we expect that he’ll somehow be elated or liberated by his condition. But the reverse is true: he’s miserable. Apart from the attentions of a corrupt CIA operative (Sam Neill) who wants to either enlist or exterminate him, which keeps him constantly on the run, he feels lonely, unacknowledged, worried that he doesn’t even exist. (“The man has a perfect profile,” notes the evil CIA agent after studying his mundane dossier. “He was invisible before he was invisible.”) He’s crestfallen when he overhears his friends callously discussing his disappearance and saddened by the reclusive life he’s forced to live. By the end of the movie, we may feel just as gloomy — even after he has got the girl (Daryl Hannah) and all the necessary accoutrements of a happy ending. His invisibility is permanent, not the standard reversible movie miracle, which undoubtedly contributes to our depression.

I suspect this is a metaphorical theme for Chase, whose star persona has been highly restricted since his early routines on Saturday Night Live, mocking Gerald Ford’s clumsiness and delivering signature lines like “I’m Chevy Chase and you’re not.” Though he started out as a writer as well as a performer, he has subsequently been typecast so exclusively as a light comic presence, without much range or personality, in fluffy, forgettable movies that it’s small wonder if he feels both invisible and trapped. (Significantly, the “real” Chase can figure here only in a dream sequence that recalls The Nutty Professor and features a fragment of Chase’s own jazz piano playing.)

Unfortunately, as happens so often in Hollywood, he can’t reject his well-known image without jeopardizing his stardom. Memoirs of an Invisible Man shows him not only fighting in vain against this limitation — trying to bring seriousness to a persona that can’t carry it (and reverting to standard gags that interfere with this effort) — but also making a movie that seems to be addressing this impasse. Insofar as it’s derived from the usual Chase persona, his character seems constructed with the sole purpose of eliciting our mild amusement, so a feeling of awkward confusion sets in when we’re asked to expect more from it. Even though one responds at times to the sentiments being expressed in the story, one has to refer to Chase himself rather than the ill-defined character he’s playing to find their human dimension.

Worse still, he can’t simultaneously service his usual fans and be invisible, so the film alternates shots of him being visible and invisible, though he is supposed to be invisible throughout. I didn’t really mind this juggling with film conventions, but I suspect some viewers may be annoyed. In short, the soft censorship imposed on Chase by his audience ultimately renders him helpless.

Paradoxically, however, the true invisible man in this movie is director John Carpenter, a personal filmmaker in every sense of the word who is effectively silenced here by another common source of soft censorship, the actor-producer — in this case Chase himself. A genre specialist schooled in the stylistics of Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock, and a dedicated craftsman who usually writes and scores the pictures he directs, Carpenter was apparently brought in as a hired gun to direct here, and the reduction in his usual effectiveness is palpable. It’s not hard to guess why: experience tells us that actors who retain final cut over directors almost never make the right artistic choices. (Just for starters, look at what Goldie Hawn did to Swing Shift, or what Sylvester Stallone does nowadays to practically everything.)

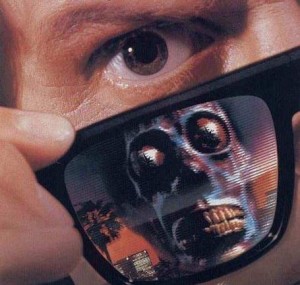

This is especially regrettable because, after losing control over Big Trouble in Little China (1986), Carpenter returned to low budgets and independence on his next two pictures, Prince of Darkness (1988) and They Live (1989), with gratifying results. The explicit and hilarious attack on Reaganism in They Live was, as Carpenter himself has suggested, the closest thing we had to the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers in the 80s. But if They Live raised expectations about Carpenter’s career, Memoirs of an Invisible Man temporarily dashes them; despite his handsome ‘Scope framing and some traces of his characteristic delicacy in handling special effects, it is probably his least personal work to date.

Clearly Chase and Carpenter have very different sensibilities; not even evidence of a shared sense of political alienation — “You expect me to trust a politician?” Chase asks rhetorically at one point — can bring these unmatched spirits together in a project that is mutually expressive, perhaps because the soft censorship that dominates today’s Hollywood tends to rule out such possibilities. In a better time and universe and film industry, the assertion of one creative personality wouldn’t necessarily entail the trampling or effacement of another.