Written in 2013 for a 2019 Taschen volume. — J.R.

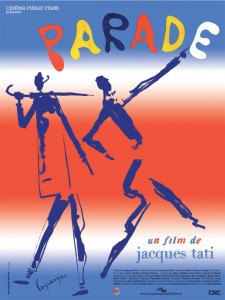

Parade

1.Why is Parade Tati’s least known feature?

It’s surprising how many of Jacques Tati’s fans still haven’t seen his last feature, and in some cases don’t even know about its existence. Yet the reasons for this neglect aren’t too difficult to figure out.

For one thing, Parade is the only Tati feature apart from Jour de fête in which his best known and most beloved character, Monsieur Hulot, doesn’t appear. For another thing, it was made on an extremely modest budget, and shot mostly on video for Swedish television; it never received even a fraction of the advertising and other forms of promotion, much less distribution, accorded to his five earlier pictures. And some of those who have seen it don’t even regard it as a feature, but think of it merely as a documentary of a circus performance in which Tati appears only as an emcee and as one of the performers, doing some of his more famous pantomime routines. It doesn’t have a story in the sense that all his previous films do on some level, including even his early short, L’école des facteurs (1947).

On the other hand, what we mean by “story” is already a bit different in the work of Tati than it is in the work of most other important filmmakers, comic and otherwise. And in fact, it could be argued that Parade does have a story, even if, like PlayTime, it doesn’t exactly have a hero — or, rather, its “hero”, as in PlayTime, consists of all the people in the movie and all the people watching the movie. And to accept that as a premise means rethinking a lot of things, including what we mean by a movie, what we mean by a circus, what we mean by a show, and what we mean by spectacle in general. And in its unpretentious way, Parade gets us to reconsider all of these things. As Tati’s parting gift to his audience, it even qualifies as his testament, but we may not be able to see this if we fail to examine the sort of expectations that we commonly bring to movies in general.

2. Video or Film? An Evolving Production and Concept

Parade was largely shot in video at a time when virtually nothing else in cinema was. The only significant exception was Frank Zappa and Tony Palmer’s 200 Motels (1971) — shot in England on videotape and then transferred to 35-millimeter film, as much of Parade would be later. The low definition of video during this period, especially color video, meant that it couldn’t be regarded even theoretically as a viable substitute for film but only as something else — chiefly as a means of recording live events that was associated with television.

But in fact, Parade as a project went through many changes. It started out in Stockholm’s Europa Film Studios in November 1971, when what Tati thought he was shooting was the first in a series of thirteen short comedy programs for Swedish TV — to be called TTV, and budgeted between two and three million crowns. (It appears that the original concept for the series included some satire about work in a TV studio that would later evolve into a separate but never realized film project, Confusion.) For the first episode, which turned out to be the only one he ever shot, Tati filmed a circus act featuring a team of acrobats called Veteranerna, or The Veterans, thirteen separate times — a dozen times in color 16-millimeter and then once again in color 35-millimeter, shooting often around the clock. The cinematographer was Gunnar Fischer — known for his work in black and white with Ingmar Bergman between 1948 and 1960, on such films as Smiles of a Summer Night, Wild Strawberries, and The Magician, and working now with his son Jens as his assistant — and the fact that Tati had never previously shot anything for television led to some confusion about the separate screen ratios for TV films and theatrical films, because Tati wanted to be able to use his material in either or both formats (which is apparently why he shot the Veterans’ act once in 35). Jan Carlsson, a famous Swedish drummer known for his work in fusion (i.e., jazz plus rock), was roused out of bed one night around midnight to play in this sequence, and Tati, who warmed to his quirkiness, got him to stick around for most of the remainder of the shoot.

Back in Paris, Tati enlisted his old pal, artist and designer Jacques Lagrange, to help him expand on some of his visual ideas about circuses, and eventually wound up crediting him for “direction artistique” on Parade. But by this time the planned budget had nearly doubled and new financing sources were needed, which took Tati a long time to find — all of 1972 and most of 1973, in fact. In September 1973, he finally signed a new contract with Swedish television that entailed scrapping TTV, including the planned TV-studio satire, and concentrating instead on a single special for Swedish TV that could be distributed in other countries and that would focus largely (if not exclusively) on some of his most celebrated music-hall routines.

As reported by David Bellos, work on Parade progressed rapidly at this point: a Swedish circus master named Francois Bronett was brought on as a consultant, other circus acts were hired, extras and a few actors enlisted, and Stockholm’s old Circus Theatre was rented for a week in late October. The most important by far of the actors were a three-year old girl, Anna-Karin Dandenell, and a six-year-old boy, Juri Jägerstedt — both of them discovered at a nursery school in Halen and reportedly enlisted not only for their photogenic qualities but, more significantly and even crucially, because they refused to follow orders. (1) In the penultimate sequence of Parade, Tati would set them loose on the empty circus stage after the show was over to play with the various props, and film their impromptu activities.

On October 29, the hastily assembled circus, Tati included, gave a performance that was shot exclusively by three video cameras for an audience made up equally of extras and ordinary spectators bringing along their kids. Both of these contingents were supplemented by life-size black and white photographs of seated spectators mounted on boards and decked out with actual colored hats, glasses, and scarves–a weird variant of the cardboard extras and photographed steel panels from Orly that were used in the backgrounds of several shots in PlayTime to create deliberately disorienting effects.

By this time, Tati had likely become aware that he was shooting what might easily turn out to be his last feature rather than just a TV special. After the shoot, he had the video footage transferred to 16-millimeter film in London to edit before being blown up to 35-millimeter to show in theater. Returning to Paris in November, he hired Jean Badal, his cinematographer on PlayTime, to shoot some additional footage in super-16-millimeter of another act, a comic musical trio who hadn’t come to Stockholm — material that then had to be reshot while being projected in Norway in order to wind up in the proper screen aspect ratio of I:I:66. And over the course of editing the diverse materials of Parade with his daughter Sophie (who had gone from being assistant editor on Trafic to the main editor here) — materials shot in video, 16mm, super-16, and 35 — Tati had to rehire both the Circus Theatre in Stockholm and most or all of the original audience, including Anna-Karin Dandenell and Juri Jägerstedt, in early 1974, to add a few more shots filmed by Gunnar Fischer and his son for the purposes of continuity.

3. A Low-Profile Release

After screening at Cannes in May 1974, Parade opened in Paris late that year, receiving a minimal critical and public reception. Tati’s reduced fortunes from the massive losses engendered by PlayTime placed severe limitations on the money that could be spent on promoting the film, and the modest production values led many people to view it as relatively inconsequential — not exactly a Tati feature like the five preceding ones but basically just a documentary of a small-scale circus show. In the U.S., where PlayTime had opened only belatedly, well after Tati’s financial problems had landed him in bankruptcy, the film wasn’t distributed at all, and when it was picked up for distribution elsewhere in Europe, most often for television, it received little attention.

When it opened in England in 1984, a full decade after it was completed, it was missing nearly fifteen of its eighty-four minutes, including its epilogue, and London reviewers who could have been expected to raise a ruckus when even some slasher films were slightly trimmed couldn’t be roused to make any protest. In 2009, however, a full version was released on DVD by the British Film Institute, and a French DVD was issued seven years earlier. It seems significant, however, that the French edition, which has been distributed to many other countries, features silhouettes of both Monsieur Hulot and an acrobat on its cover, even though Hulot makes no appearance at all in the film. Commercially, it would seem that such a misleading icon was deemed essential — perhaps because, even long after Tati’s death, Hulot has remained a far better known figure than his creator. Furthermore, it appears that Tati’s concerted effort to undermine his own status as a star — here and in PlayTime, as part of his strategy for elevating the importance of the audience — succeeded all too well.

4. Plot and Principles

Parade’s title appears over a drumroll, in the form of a multicolored marquee in the night sky above a circus building, and the camera pulls back from this building before cutting to a closer shot of people filing in. Then the first “gag” occurs –- a detail so slight that by conventional standards it hardly qualifies as a gag at all, although it is quintessential Tati: a teenager in line picks up a striped, cone-shaped road marker on the pavement and dons it like a dunce cap; his date laughs, finds another road marker, and does the same thing.

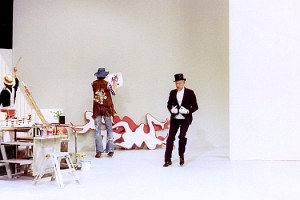

At least three basic principles of Tati are set forth in this passing detail. There is the notion of bricolage, or the appropriation of impersonal objects for personal use that enables people to reshape and reclaim their environment, an idea central to Tati’s work (the restaurant sequence in PlayTime formulates it on an epic scale), which reaches its distilled essence throughout Parade, both offstage and on. (Tati, one should stress, directed all the stage acts himself, altering in some instances the performers’ usual props, costumes, and gestures, such as getting the jugglers to juggle with paintbrushes –- another good example of bricolage.)

Then there is the offhand inflection and punctuation of the gag, making it a slightly disorienting moment of strangeness in the midst of normality rather than the conventional setup followed by a payoff. (Critic Jean-André Fieschi has aptly noted that Tati’s gags “are not placed in salient positions, as are the bon mots in boulevard theater. Every remarkable idea seems clogged, every flash of wit annulled in a kind of imperturbable equalization.” (2) [Note: My only source for this quote is in English; it may not be available anywhere in French.] As a consequence, the dunce-cap gag is more likely to make us smile than laugh; but the cumulative effect of dozens of such underplayed gags is to make reality itself seem both slightly off-kilter and alive with comic possibilities — every moment brims with potential gags that often require an audience’s alert participation in order to be noticed at all.

Finally, one should note that at the very outset, Tati is placing spectators rather than performers in the primary creative role. The “parade” begins before the audience even enters the theater, as is fully apparent in the brightly colored, festive, and flamboyant clothes worn by the hippies in the audience as well as the props carried by many of the younger kids. The implication of this principle, along with the preceding two, is that Tati’s democratic aesthetics are more than just a matter of everything and everyone in a shot being worthy of close attention. They also function on a temporal plane –- every shot and moment is worthy of close attention, and a moment without a fully articulated gag is not necessarily inferior to a moment with one, because the spectator’s imagination is unleashed by the mere possibility that one might occur.

One of the kids, Anna-Karin Dandenell, wearing a play gun and holster, stops briefly inside the lobby to adjust her gear, and briefly makes eye contact with Juri Jägerstedt before each of them is dragged off in opposite directions by his or her parent (her mother and his father). These are the same two kids who will literally take over the movie in the epilogue, entering the empty stage and playing with various props as they try to reproduce the acts they have seen. They are also seen periodically in the bleachers throughout the show –- she in the front row, he behind her –- and their responses to the show and each other are accorded at least as much attention as any of the acts.

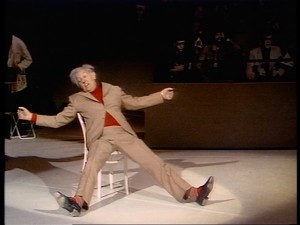

The movie lingers over a good many other preliminaries before the circus actually begins: people drifting to their seats, musicians tuning up, carpenters and painters (who later prove to be performers) working on props. The fact that these activities are as important as what follows dawns on us only gradually, in part because it becomes difficult to determine when and where the show does begin. When the opening trumpet fanfare is played by two clowns in the bleachers, many spectators are still arriving, and the camera seems so distracted by such details that we come to accept the fanfare, the following introduction of performers, and a subsequent drum fanfare as part of the preliminaries, too. Even when Tati himself strolls onstage in a top hat and is greeted by applause, the camera abruptly sweeps past him to settle on the front rows in the bleachers, where Juri is visibly bored out of his wits, and Anna-Karin, while applauding (along with her mother) in the row ahead, is looking at Juri, not at Tati.

When Tati, the official master of ceremonies, begins to speak, it is in a multilingual, semi-nonsensical patter that goes something like this: “We have the pleasure of presentera a show where everybody can, for I may, I am pleased to include you, me, we are all together around ménage called parade -– ” But then the camera cuts away from him again to focus on the drifting trajectories of a wandering toddler, proceeds out into the lobby to linger on a latecomer checking his motorcycle helmet at the cloakroom (which makes a loud clunk when it hits the counter), remains with the befuddled female attendant surrounded by a sea of other helmets, then proceeds down a hallway to the comic entrances and exits of a hockey player and a violinist. When the camera finally returns to the auditorium, it is to the bleachers, where another motorcyclist is asked by the woman seated behind him to remove his helmet so she can see better –- but his decompressed hair creates even more of an obstruction. Finally we get to see the musicians playing onstage, but from an oblique overhead angle that includes the stage rigging.

Even when the camera spends more time on the stage, the physical borders of spectacle and audience are broken down through a variety of means. The painters and carpenters working on props are frequently visible and even prominent as spectators during some of the acts. (Only much later, when a painter starts competing with an onstage magician in performing card tricks, and when several of the painters start juggling with their paintbrushes, does it become fully apparent that these characters are “performers” rather than “extras.”) An onstage row of fake bleachers containing the black-and-white cutouts of spectators is integrated into some of the acts; this effect is undermined in turn when real spectators are later glimpsed in the same spot, or when fake spectators are glimpsed in the actual bleachers. Time and space often become mutable, but the premise as well as the illusion of a show taking place in real time and on a single stage is rigorously maintained.

5. Chance versus Control

A central aspect of Parade that makes it more contemporary and more in tune with advanced filmmaking than all its other qualities is its complex interaction between nonfiction and fiction, chance and programming –- a dialectical approach followed with comparable fruitfulness in such films as Jacques Rivette’s Out 1: Spectre, Orson Welles’s F for Fake, Chris Marker’s Sans soleil, Francoise Romand’s Mix-Up, Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan’s A Story of the Wind, and several shorter films by Peter Thompson and Leslie Thornton.

Although the visual definition in the studio-filmed portions of Parade is noticeably sharper, the mixture of materials is so deft in other respects that it is generally impossible to separate the documentary segments from the fictional details. The sole exception to this is the film’s epilogue and pièce de résistance, in which Juri and Anna-Karin are left alone with the stage props after the show has ended. Tati shot two hours of their improvised play with several video cameras, then extracted the few minutes that are used in the film.

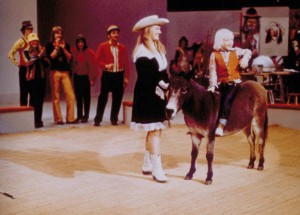

The studio shooting of PlayTime, which entailed the construction of an entire city set, precluded such experimentation, but some early forays into documentary can be found in certain sequences of Trafic, detailing the behavior and habits of various drivers, which are so gracefully threaded into the rest that they register as a continuation of the fiction rather than a departure from it. Here, too, it is not always clear what ‘s accidental and what’s carefully planned. When various members of the audience accept the dare to ride one of the bucking mules, the fellow wearing glasses and a badly pressed suit who unexpectedly triumphs is actually an acrobat is disguise. It’s perhaps only when we arrive at the unsupervised and idle antics of Anna-Karin and Juri on the empty stage towards the end that we can be sure we’re watching pure improvisation.

6. The Radical Vision of Parade

Sometimes the most radical and profound ideas turn out to be very simple. Some of the most radical and profound ideas in Parade are at least as old as the paintings of Brueghel, although they’re a good deal fresher and considerably more advanced than those in most commercial features being made and released forty years later. A few of these ideas can be represented in simple sentences, all of them having to do with the nature of spectacle, and all of them saying pretty much the same thing:

There is no such thing as an interruption.

There is no such thing as “backstage”.

At no point does life end and the show begin — or vice versa.

Amateurs and nobodies–that is to say, ordinary people — are every bit as important, as interesting, and as entertaining as professionals and stars.

Poetry always takes root in mundane yet unlikely places, and it is taking place all around us, at every moment.

These are all simple ideas, and in the film they’re all expressed exclusively in terms of light entertainment. Yet even four decades after Parade’s initial release, they remain elusive, difficult, complex, and highly subversive in relation to most notions about the art of spectacle that continue to circulate. Worse yet, they are often expressed in terms that are unfashionable, in relation to either 1973 or the present, if we consider such things as the rock band that performs in the film.

7. Tati returning to his origins

Among the acts included — tumblers, musical novelties, a singer (Pia Colombo) introduced from the audience, and an audience-participation interlude involving an obstreperous mule –- are many of Tati’s most famous music-hall pantomimes, depicting a football game, a fisherman, a tennis match, a tennis player circa 1900, and a horseback rider. The continuity between these solo routines and Tati’s directorial style is that both appeal to a spectator’s imagination through a panoply of subtle suggestions. (Reviewing one of Tati’s mime performances in 1936, Colette wrote, “Il a inventé d’être ensemble: le joueur, la balle et la racquet; le ballon et le gardien de but; le boxeur et son adversaire, la bicyclette et son cycliste.“ [“He has created at the same time the player, the ball and the racket; the football and the goalkeeper; the boxer and his opponent; the bicycle and its rider.”)

While it might seem from the foregoing description that Tati somehow undercuts the performers (himself included) in order to glorify the spectators, he actually treats them all with respect. His directorial sleight of hand keeps bringing the audience into the act, but never in such a way that it betrays or impugns the talents of any of the performers, including his own. It is the ideology of spectacle and its attendant hierarchies that he is out to dismantle –- not the pleasures of spectacle itself, which he is in fact inclined to spread around liberally and democratically, emphasizing its continuities with everyday life.

In this manner, Parade creates a privileged zone of its own in which the free play between fiction and nonfiction becomes an open space to breathe in. It is a utopian space where equality reigns between spectators and performers, children and adults, foreground and background, entertainment and everyday life, reality and imagination –- an evening’s light diversion that, if taken seriously as well as playfully, as it was meant to be, could profitably crumble the very ground beneath our feet.

End Notes

1. Bellos, David, Jacques Tati, London: The Harvill Press, 1999, p. 318.

2. Fieschi, Jean-André, “Jacques Tati,” translated by Michael Graham, Cinema: A Critical Dictionary, vol. 2, edited by Richard Roud, London: Martin Secker & Warburg, 1980, p. 1004.

3. Quoted in Goudet, Stéphane, Jacques Tati, de François le facteur à Monsieur Hulot, , Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma/les petits Cahiers/CNDP, 2002, p. 8.